- Jeb Wallace-brodeur

When David Patrick Adams listens to people's life stories, their journeys can resemble the flights of glider pilots. In cross-country races, explained Adams, who is a licensed pilot, competitors sometimes fly in a different direction from their intended target to catch the thermals that will carry them to their destination.

The 19th-century philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson described a well-lived life in similar terms: "The voyage of the best ship is a zigzag line of a hundred tacks. See the line from a sufficient distance, and it straightens itself to the average tendency."

For eight years, Adams, 74, has been chronicling the zigzag lines of people's lives, including their random and serendipitous tangents. After a career of launching many other businesses, his current one involves conducting video interviews of clients and then creating personal documentaries about them, similar to the approach of Ken Burns.

But unlike the work of the famed filmmaker, Adams' "portrait interviews," as he calls them, might be seen by only a handful of people — perhaps just family members and close friends — and sometimes not until after their subjects have died. Each "portrait" is like a message in a bottle to future generations.

Adams' clients aren't necessarily rich or famous. He's interviewed doctors, lawyers, artists, musicians, farmers, teachers, bankers and entrepreneurs, all of whom are of varying ages and nationalities. What they have in common, he said, are accumulated experiences and insights that they wish to preserve for posterity.

Adams' own zigzag journey has taken him across multiple continents. A native of Buenos Aires, Argentina, he was raised in Brazil and educated in Europe before moving to the United States.

A lodestar in Adams' life has been an inclination to continually reinvent himself. He's worked in higher education, commercial real estate, advertising, consulting, professional mentoring and philanthropy. In addition to flying planes, he is also an avid horseman and former skydiver and marathon runner.

Having "retired" at 50 with financial independence, Adams was motivated by something beyond the accumulation of wealth.

"I want to have good conversations with people," he explained in an interview. "The philosopher Martin Buber says, 'All real life is meeting.' I want to engage ... on a deeper level with people because I want to understand what the hell this is all about."

Adams agreed to an interview at his wooded hilltop home in Northfield, where he lives with his wife and business partner, Brazilian artist Maria Lucia Ferreira. The conversation began in their living room, where Adams, who's tall, lean and angular, sat with one leg folded over the other, like an origami bird.

Though ostensibly the interviewee, Adams occasionally reverted to the role of interviewer, asking probing questions about his guest. He then watched intently with slate-blue eyes, listening for and remarking on revelatory biographic details.

Adams' British accent reflects his education at an elite English boarding school and college. He moved deftly among different subjects, variously quoting Claude Lévi-Strauss, the French ethnologist and anthropologist; William Wordsworth, the English Romantic poet; and Leonard Cohen, the Canadian singer-songwriter.

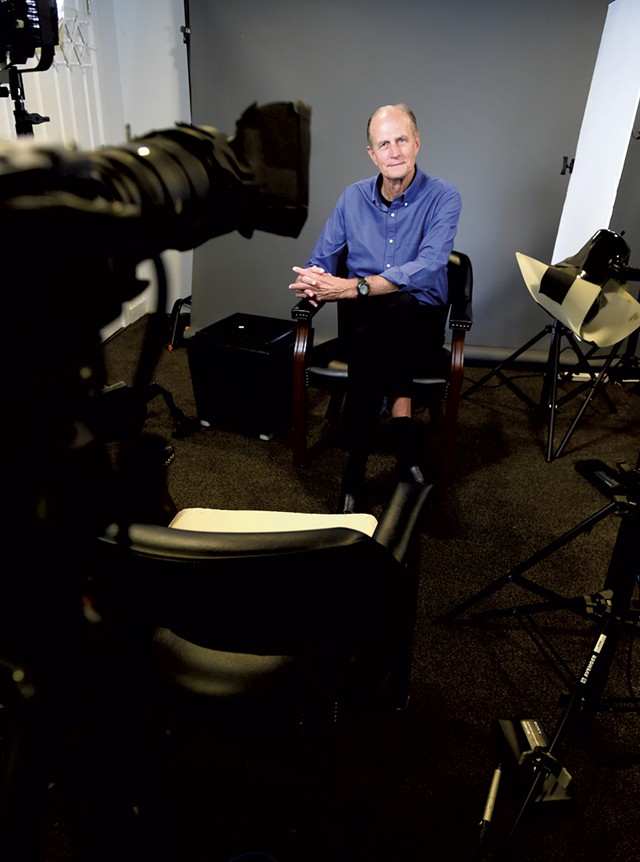

Halfway through our conversation, we adjourned to Adams' basement studio, where he conducts most of his interviews. Others he does at his studio in Rio de Janeiro.

Typically, Adams breaks up his interviews into two two-hour sessions: one in the morning and the second in the afternoon. Portrait interviews start at $3,500 and cost more if additional editing, music and photos are included. The final products vary in length, from 15 minutes to an hour.

In the studio, Adams sits across from his subject, who is surrounded by light stands and sound baffling. Just over Adams' right shoulder, and slightly obscured in the darkness, is a video camera. Once everything is operational, Adams conducts his interview with no one else in the room, both to minimize distractions and to forge a stronger bond with his interviewee, he explained.

"It becomes very emotional and intimate," Adams said. "It's a wonderful generosity of spirit to be able to get so close to somebody."

Contrary to what some may assume, Adams' clients don't come to him out of vanity, though some, he acknowledged, want to shape their legacies.

"Many people do these interviews because they want to get a sense of their lives," he said. "[Danish philosopher Søren] Kierkegaard once said that we live our life forward but we understand it backward ... What you're doing right now will only make true sense to you in another 10 or 15 years."

Other clients are motivated by an existential awareness of the experiences they know they'll never have. One man, who married and had a daughter late in life, regretted that he won't be able to have an adult conversation with her. Adams recounted the man's instructions: "I want you to ask me the sorts of questions my daughter will want to know when she's 35, 45, 55 and 65 [years old]. So in the future, she can watch this interview and I can at least answer some of her questions."

On-camera introspection doesn't come naturally to everyone.

"For some people, a conversation like this is a very unusual thing," Adams conceded. "But to have someone spend four hours talking about their life can be extremely moving and important."

Donny Boardman, an 81-year-old retired teacher from Northfield, sat for a portrait interview recently. He described Adams as "an excellent questioner" who "made me feel completely at ease. I was able to talk more freely than I would with someone else."

Once Adams and his wife completed the final edit — typically, it takes about two weeks — he sat down with Boardman, as he always does with clients, and showed him the finished product.

Boardman described the experience as "an eye-opener ... It was like looking in a mirror and seeing my whole life flash before me."

Friedrich "Fritz" Gross, a 72-year-old Swiss artist living in Corinth, had a similar reaction. He had a portrait interview created several years ago as a gift for his daughter. When asked how it felt seeing himself on-screen for the first time, he chuckled.

"It was something else!" Gross recalled. "It was almost like watching a documentary of someone I knew really well. And I agreed with him. I said, 'Yes! That's exactly the way it was!'"

Though Adams' interviews aren't confrontational or confessional — "I'm trying to bring out the very best in that person," he said — he wants the audience to see the individual's many facets.

Often, personal truths emerge unprovoked. Some clients have confessed their closeted sexuality. Others have revealed wrongs they've inflicted upon loved ones or revisited childhood traumas. Gross, who recounted the scene of his mother's death when he was young, urged other interviewees to be equally forthright.

"Otherwise," he added, "you're wasting your time."

Adams acknowledged the therapeutic quality of the experience.

"Each one of us steps into the world as a young adult with a suitcase in our hand that has been packed, almost entirely, by other people," he explained. "Then, when we get out in the world, we look in the mirror, and say, 'These clothes aren't me. These are my father's clothes!' I'm still discovering things in my suitcase that other people put in."

Indeed, the idea for this business came to Adams when he began writing his memoir and unpacking his own "suitcase."

He described his family as "English empire types" who arrived in Argentina in 1850. His grandfather, an engineer born in Tasmania, helped build the railroad that runs from Buenos Aires to Patagonia.

In Adams' family, it was customary for sons to attend English boarding schools from an early age. So at 12, he was sent to the Abbotsholme School in Staffordshire, which he described as "very spartan." His father, a salaried worker, rarely could afford to bring him home.

"From the age of 12 to the age of 18," Adams recalled, "I saw my parents three times."

He described being uprooted from the child-centered culture of Latin America and sent off to England as "emotionally catastrophic."

During Adams' teenage years, his legal guardian in England was John Hunt, the British Army officer who, in 1953, led the first successful expedition up Mount Everest.

"It was both good and difficult, because all I saw was a circle of famous people," Adams recalled. "When I left, I said [to myself], The only way you're going to attract attention or be important is by doing something extraordinary."

In 1967, after earning a bachelor's degree in Portuguese and French literature at King's College London, Adams arrived in New York City with plans to become a famous writer. "But I had nothing to write about," he recalled with a laugh.

So he hitchhiked around the U.S., eventually taking a job in Niagara Falls, N.Y., operating a jackhammer and drilling holes for construction dynamite. After a string of odd jobs, he landed in Boston and earned a master's degree in English at the University of Massachusetts. There he became a lecturer teaching 20th-century Portuguese literature.

In Boston, Adams became passionate about skydiving; he briefly held an unofficial world record for forming the largest (29) free-fall circle of skydivers.

"To me, in a way, it was my John Hunt expression," Adams said. "John had climbed Everest. And I was going to be the world's best skydiver."

After a few years, Adams realized he was ill-suited for academia. With a liberal arts background, he founded the Linley Group, a Boston advertising and consulting firm. Ten years later, he launched the Linley Companies, an international real estate practice. In 2000, Adams returned to corporate consulting. In 2007, he founded the nonprofit Linley Foundation, in northeastern Brazil, doing educational, environmental and animal-rights philanthropy.

Adams' numerous course corrections have served him well as an interviewer, because he seeks out similar turning points in his interviewees' lives. Turning to another travel metaphor, Adams likened those events to the clacking timetable boards in train stations that announce arrivals and departures.

"Something happens in your life, a train comes in or goes out, and you don't even notice it," he said, "but the whole board changes."

To wit: When Adams married Ferreira, his second wife, he essentially "parachuted" into parenthood — at age 55 — and now has two grown stepchildren.

Early on in his business, Adams sat down for his own portrait interview, with his wife as interviewer. It was important, he explained, to understand what the process felt like. And, like some of his clients, Adams plans to revisit and update his portrait interview in several years. Why?

To answer, he quoted author Henry James: "Nothing is my last word on anything."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.