Teenage protagonists are unreliable narrators, almost by definition and through no fault of their own. Teens are walking existential crises: From friend feuds to school plays to weird crushes, they lack the maturity to see the larger picture and put moments of conflict in perspective. Also, adolescence is a time of sussing out one's life. Each teen experiences this differently, and others can only hope to make sense of it.

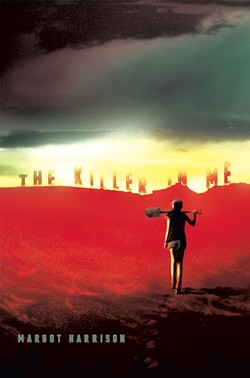

This is the premise upon which Vermont author Margot Harrison's debut young adult novel, The Killer in Me, is founded: Is 17-year-old Nina Barrows crazy? Can she be trusted to put her own terrifying experiences in context with the world around her? Is she truly experiencing a supernatural psychic connection with a serial killer, or are her "dreams" — of a young veteran who kills people at random — simply the onset of schizophrenia?

From the beginning of Nina's story — an exploration of the delicate contours of family, trauma and adolescence — the reader must latch onto this crazy-psychic binary in order to make sense of its twists and turns.

The only adopted child of a lesbian hippie mother in Vermont, Nina describes the typical banality of high school, hormonally shifting relationships and recreational prescription drugs in a rural community. All of this is rendered even more banal in contrast to one defining reality for Nina: As long as she can remember, her only dreams are those in which she experiences the life of a complete stranger, Dylan Shadwell — she refers to him as "the Thief" — who, after an uneventful military tour in Afghanistan, suddenly decides to murder people for sport.

In her sleep (she's on Eastern Standard Time, while Shadwell is two hours behind in Albuquerque), Nina becomes a witness to his meticulous planning and the horrific brutality he exacts upon victims around the country. The Thief seemingly has no preferences or habits regarding his targets' identities or the circumstances of their deaths. (An FBI analyst might scoff at the idea of a serial killer without an MO, but this unpredictability makes him all the more terrifying.)

- The Killer in Me by Margot Harrison, Disney-Hyperion, 368 pages. $17.99.

Whether Shadwell is real or Nina's delusion, the never-ending invasive experience is traumatic. In an effort to avoid sleeping, she mainlines caffeine and Adderall purchased from estranged childhood friend Warren Witter. She isolates herself, emotionally and physically, from practically everyone around her.

Nina's psychological afflictions seem more like those typically associated with abuse or sexual assault than with psychic links to (possibly imaginary) psychopaths. Her physical description — "kinda disheveled and pale, with those huge eyes ... like the heroine of a murder ballad" — only adds to the seriously disturbing portrait of her inner life.

For readers who have bet against the supernatural (many of us, after all, have seen Fight Club), there is down-to-earth respite in Warren. Once Nina confesses her secret to her childhood buddy — knowing full well he's in love with her and is also useful with a gun — his voice becomes a humanizing buoy amid her nebulous, often frantic account. Warren's first-person narration is interspersed with Nina's own so that, together, they tell a two-sided version of her predicament — what it feels like, and what it looks like to everyone else.

Like the reader, Warren wants to believe her; the alternative is almost more tragic, at least for his lifelong crush. But when we begin to suspect that Nina is Holden Caulfield-grade unreliable, his steadfast devotion keeps us on board with their mission.

Warren's own struggle is with more concrete problems: how to transcend the shadow of his redneck criminal father and brothers, or whether to abandon his neglected mother and seek the college education he really wants. (Also, how to keep Nina in his life without being a total creep.)

Warren and Nina take a road trip from New England to the Southwest. To their parents, it's a trip to visit colleges and meet Nina's birth mother; to the teens, it's in search of the Thief and the bodies he's buried in the desert. But, of course, the journey is ultimately about vindication — of Nina's sanity, of their relationship and of their post-high-school future.

It's in describing this trip that Harrison's writing truly shines. She's at her best when painting landscapes, from Vermont in the soggy springtime to the scorching, merciless expanse of southwestern deserts in summer:

Green has bled out of the landscape. The red sun slants on distant anthills of beige sand, and I wonder why anybody ever put down roots in the desert. It looks sterile, dry, dead, like outer space.

Harrison shows us America-by-highway through adolescent eyes, complete with perfectly manicured suburbs, front-yard trees decked out in bird feeders, abandoned shacks and secret turn-of-the-century mines. The Killer in Me is as much atmosphere as story.

The author also gives us a handful of understated narrative moments from both Nina and Warren that are genuinely funny — frivolous personal moments in a landscape of nature's dusty indifference and a dark portrait of evil. (Even if unreliable, the teen voice can be a gold mine for charm.)

Regardless, the all-consuming aspect of Nina's life makes it hard to bond with her. In part that's because we don't learn much else about her, aside from her interest in Warren's Philip K. Dick book, once, in middle school. In addition, the story's suspense is sometimes compromised by a narrative timeline that lurches forward and backward.

It's tempting to think The Killer in Me is addressing teen depression or the quest to conquer one's unpleasant origins. (Perhaps Nina's adoption stemmed from horrors committed in front of her, inflicting deep-seated trauma that would take years to unpack.) Ultimately, though, the book's tension balances on the essential question of whether Nina is sick or sane. And that makes for a less satisfying or complex ending than the narrative's constant uncertainty leads us to expect.

Still, what this novel has in spades is ambience. The cinematic qualities of Nina and Warren's adventure would lend the story to teen-thriller film treatment. One can imagine the montage in which he teaches her how to shoot a gun, for example, or another in which they bond over days of midwestern highways and junk food and 24-hour-diner breakfasts. A cinematographer, director and actors could give more weight and subtlety to the book's moments of tenderness, insecurity and clarity.

Days after reading The Killer in Me, a reader's mind will certainly linger out in Harrison's blistering desert, whether or not Nina was right about it.

Disclosure: Margot Harrison is associate editor at Seven Days.

From The Killer in Me:

He calls himself the Thief in the Night. He likes to think he's invisible. That's why he doesn't talk, doesn't torture, doesn't interact with them until he has to. Like death itself.

"They" are his victims. He calls them "targets."

First came the old man. Then the homeless guy. The hitchhiker. The lady who ran the campground. The woman in the honky-tonk parking lot.

And now this couple in upstate New York, the Gustafssons.

He found them two Mondays ago when he was in Schenectady for a scale-model conference. He hadn't planned to get into any trouble there (his private code word for killing somebody is "trouble"). But his eyelids felt gritty, the telltale sign he wouldn't be able to sleep, and the left lid kept twitching like it sometimes does. He should've pinched a couple Ambien from his girlfriend back in Albuquerque, but it was too late now. So he slid the battery out of his phone, took a random exit into a quiet neighborhood of little ranch houses, and went hunting.

He looked for a house with no dog, no kids' toys, access through the garage, a master bedroom facing away from the street.

He found one.

He hadn't brought any tools so everything stayed theoretical. When he hunkered down behind a bare lilac bush and examined the house, he saw it as a puzzle. A mission.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.