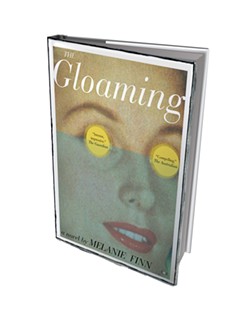

These are the questions confronting Pilgrim Jones, the drifting protagonist of Melanie Finn's The Gloaming. Set in Tanzania and Switzerland, told in brief chapters that leap through time and space, this ambitious novel addresses age-old questions through the story of one woman's abrupt alienation from her own life. It's an immersive, atmospheric read that is difficult to shake.

Finn, who currently resides in Vermont's Northeast Kingdom, was born and raised in Kenya. As an adult, she lived in Africa as a filmmaker and a medic to Tanzania's Masai community, and founded the Natron Healthcare Project to bring care to that remote area. The Gloaming, her second novel, was originally published last year as Shame in the UK, where it was short-listed for the Guardian's Not the Booker prize.

While the book's U.S. title captures its frequently eerie, liminal ambience, the UK one cuts straight to the heart of Pilgrim's personal crisis. We meet this first-person narrator as she accompanies a wealthy American couple on a safari through the Tanzanian bush. When they reach the remote, "dead-end" village of Magalu (see excerpt), Pilgrim makes a startling decision to stay — not because the place has anything to offer her but because, she says, "I can't go back."

- The Gloaming by Melanie Finn, Two Dollar Radio, 318 pages. $16.99.

Flashback chapters, alternating with the present-tense narrative, show us what Pilgrim can't go back to: a failed marriage to a human-rights lawyer. A lonely life and an unpaid phone bill in a tidy Swiss village. And, worst of all, the whispers of Kindermörderin — "child murderer" — that began after the tragic car accident she doesn't remember.

Pilgrim has been legally cleared of blame for that accident. Yet, when a hideous relic shows up in Magalu, designed by a witch doctor to curse its recipient, she suspects it was meant for her. She flees to a coastal resort, where she meets fellow expatriates with their own reasons for disappearing into Africa. But there, too, Pilgrim begins seeing — or thinking she sees — signs that her past is catching up with her.

Pilgrim's lyrical, moody, not-always-reliable voice dominates the novel's first half. The second half pulls back, using a radically different narrative strategy, to give us a stronger grasp of the events that led to her African sojourn and will follow from it. In the process, Pilgrim's story becomes intertwined with those of a diverse cast of characters: a Swiss police detective, a Ukrainian mercenary, an undersupplied Tanzanian medic, a woman from the American heartland who dreams of running an orphanage for children of AIDs.

All of their tales return sooner or later to the idea that violence begets violence, a "curse" that is self-fulfilling and self-perpetuating. Examining the witch doctor's relic, a local policeman suggests that it might be shame, not supernatural forces, that actually kills the recipient: "Imagine someone hates you this much? What have you done to him? Perhaps in your heart you know you are guilty. And this magic speaks to your heart." Such curses might be broken by self-forgiveness, but for Pilgrim and the other characters, that remains an elusive form of redemption.

Finn's prose style is lucid and terse, never showily "literary," yet she achieves impressive feats of description. When Pilgrim steps outside Magalu to explore "the stuttering, fidgeting bush," she finds a road "bisect[ing] the green, drawn with all the certainty of a three-year-old's crayon, wobbling, but indelible." When the detective enters the home of a recently deceased child, Finn conveys the intensity of a parent's grief with a simple inventory of the toys that lie strewn in the living room, waiting to be played with: "Later hung upon the air with the almost visible density of dust."

The Gloaming sometimes recalls Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness, not only in its scenario of a white person taking a symbolically laden African journey but in its use of landscape to produce a mounting sense of dread. The key differences are that Finn treats her Tanzanian characters as people, not as frightening ciphers — and that her "heart of darkness" has no geographical location.

The witch doctor's curse may evoke old colonialist narratives about "savages," yet we soon discover that the hunger for supernatural vengeance can arise anywhere. Death can strike as swiftly and horrifyingly in the postcard-perfect Swiss village as it does in Magalu.

Perhaps Europeans are simply better at pretending that horror is an aberration. In one of the novel's most chilling passages, Dorothea, the Tanzanian medic, explains to Pilgrim why the ragged children who live in the bush seem prone to unreflecting violence: "You maybe feel shame for them, but they do not feel shame for themselves. They are strong, because their brothers and sisters who are weak have already died."

Slow and meditative in its first half, The Gloaming becomes more like a conventional thriller in its second. Some readers may balk at the coincidences that push the plot toward resolution; occasionally, the novel may remind us of those globe-trotting, Oscar-bait movies that advance the thesis "everybody is connected." But Finn's tough-minded prose and brutally believable dialogue prevent her book from slipping into platitudes.

Pilgrim will eventually learn that her choices still matter, and the author earns those hopeful moments with her harrowing explorations of despair. The book's most powerful passages embody both. When Dorothea explains to Pilgrim why the surviving children of the bush live without scruples, she uses an image that evokes the ubiquity of death but also the continuity of life. Like Pilgrim, the children live in a land fed by corpses. Yet they accept their survivor status without guilt and move on to continue the cycle: "Here are more babies than rocks buried in the soil. It is too crowded. There is no room for shame."

From The Gloaming

Bob says, "This is no joke, sweetie. We should be going to a real hospital. Not some quack shack in the middle of Tanzania."

A grand roundabout heralds a town. A town of sorts. The cement structure at the juncture of two dirt roads comprises a series of flying arcs. But I'm unable to interpret the artist's vision as a large section has crumbled, revealing a rusting rebar skeleton. Perhaps there was supposed to be a fountain, but the cement floor has cracked wide open. Instead of sparkling, glittering water, the roundabout holds all manner of trash, which is picked over by chickens and children.

"Where are we?"

Jackson slows momentarily to avoid a goat. "Magalu."

"Magalu, Christ." Bob peers out the window. "It's goddamn Splinterville."

"What comes after Magalu?" I ask Jackson.

"Nothing."

"It's a dead end?"

"Yes," he says. "It is a fully dead end."

"For God's sake, sweetie." With his bandana, Bob pats away the spittle on Melinda's face, "We have good insurance, we're fully covered for evacuation."

Low-slung breeze-block buildings extend beyond the roundabout. Small side streets drift off between these buildings to mud-and-wattle shacks. But beyond them, Magalu loses interest in itself. The thick, knobby bush resumes, relentless, interminable, muttering on until the sky. The rolling geography of the land means the horizon could be anywhere. Am I seeing a hundred miles or twenty?

Jackson stops in front of what must be the clinic. The white-wash is fresh, the door marked with a painted pale blue cross. Perhaps this is a good sign: someone, after all, cares.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.