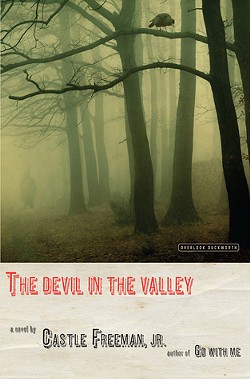

- The Devil in the Valley by Castle Freeman Jr., the Overlook Press, 192 pages. $24.95.

More than one reviewer has compared Newfane novelist Castle Freeman Jr. to Cormac McCarthy. That weighty association may have helped inspire the new film based on Freeman's 2008 novel Go With Me — starring and produced by Anthony Hopkins — that recently premiered at the Venice Film Festival. But it isn't a very good description of Freeman's work.

Where McCarthy tends to the brilliantly ponderous, the Vermont writer is about as terse and plainspoken as novelists come. And where McCarthy unveils dark visions of the rule of brute force, Freeman seems more interested in rough-hewn social orders that work pretty well, glitches aside. His is the un-awed tone of an oral storyteller who sees humanity as intrinsically flawed — otherwise, what stories would we have to tell? — but rarely rotten to the core.

Neither sentimental nor nihilistic, that tone has never sounded more clearly than in Freeman's new novel, The Devil in the Valley, in which he gives the Faust legend a woodchuck spin. The setup is simple and familiar. A stranger — introduced as "Dangerfield, the account man, the closer" — comes to rural Vermont to pay a visit to a reclusive retired schoolteacher named Langdon Taft.

What Dangerfield is and wants is never in doubt — he can manipulate space and time, and he offers Taft a "deal" with a contract to match. Taft, who knows his Marlowe, doesn't need anyone to explain to him that, after seven months of wishes magically granted, this dapper little salesman plans to carry him off to "the hot place." But Taft's "not worried. Why? Simple: Not a believer." Regarding the soul as a fiction, the crusty old drunk tells himself, "You beat the devil, not by superior play, but by ignoring the game."

This isn't a new twist: Skepticism is built into the Faust character, along with prideful self-deception. What's novel about Freeman's version isn't how Taft doubts the existence of hell but how he chooses to use the devil's power. Here there's no hookup with Helen of Troy, no consorting with witches. Forgoing such traditional hell-granted benefits as youth, wealth, power and sex, Taft instead pays a child's hospital bill, gives a wife beater a taste of his own medicine, prevents a foreclosure, even punishes school-bus bullies. In short, this is Faust as a Capra-esque do-gooder.

Which poses a quandary: Contract or no contract, does Taft deserve to be carried off to hell? On the one hand, the devil would allege that the schoolteacher takes selfish pleasure in his altruism. Good deeds give his life the one thing he craved before Dangerfield's arrival: "a plot." On the other hand, Taft would argue that he has successfully diverted the devil's power to better ends. To his mind, Dangerfield's obsession with the "glib, familiar" language of greed and commerce is his downfall: "Let him see how a gentleman sells his soul."

The story plays out in short, episodic chapters, some of which could almost stand alone. The tales of Taft's exploits alternate with chapters similar to the "Greek chorus" passages in Go With Me; in these, Taft's sole friend and confidant, Eli Adams, visits the local hospice to gossip with a scrappy 98-year-old named Calpurnia. At first, these chapters seem to offer little beyond the pleasures of Calpurnia's acerbic commentary. But gradually a closer connection to the main storyline is revealed.

Freeman's writing has a theatrical snap rather than a cinematic sweep. His great strengths are in dialogue and omniscient narration that sounds like dialogue, or like expert campfire storytelling. Even a reader who balks at the novel's metaphysical aspects will savor it, sentence by sentence, chuckling frequently. Take Freeman's description of Calpurnia: "She had all her marbles and quite possibly a few of yours." Or the introduction of the wife beater: "Wesley figured as a sort of local hero in reverse." Or Taft's response to Dangerfield's warning that hell is for eternity: "We're in Vermont, remember? For us, Eternity is another name for March."

Quotable as they are, such one-liners transcend the folksy. In context, they read as the laconic language of people who know that, without a few laughs, without a "plot" — or multiple plots — another March might not be worth enduring. And the devil is happy to supply a show. "We're in show business, here," muses Dangerfield about his power. "End of the day, it's vaudeville we're in."

As Taft uses that showman's power to amuse himself and keep the despair of a "backpacker in the Dark Wood" at bay, so Freeman uses it to amuse the reader — in some chapters more successfully than others. A few characters, such as a rapacious big-city banker who's actually named Raptor, are drawn more broadly than they need to be. But they don't prevent the novel from working just fine as tall tale and "vaudeville" — a succession of absurd confrontations and compelling what-ifs.

What of those metaphysics, though? While Marlowe had his Faust carried off to hell as promised, Goethe got abstract and prolix when he couldn't square the legend's traditional ending with his Enlightenment rationality.

Prolixity isn't Freeman's style, and neither is standard-issue piety. Calpurnia mocks the village minister's sermonizing for its irrelevance to real life. In this author's fiction, doing good can be a dirty job. Go With Me is about the frontier justice of eliminating a destructive bully, but it's frontier justice that works. So do most of Taft's schemes, even when they have unintended consequences. By that pragmatic measure, it's hard not to see a hero of sorts in this whiskey-swilling woodchuck who sets out to outwit that ultimate bully — the devil — and does what his literary predecessors could not.

From The Devil in the Valley

Those having business with Langdon Taft tried to get to him by eleven in the morning. For Taft, the clear, bright hours were his best. He felt his momentum build from waking to about eleven. Eleven was when momentum slowed and distraction set in. Distraction, diversion — or the need of them. Or of their substitutes. One substitute in particular. Eleven was when Taft was known to pour his first dram of Sir Walter Scott. An ex-gentleman, ex-teacher, ex-scholar, ex-householder, ex-abstainer, he was retired from many things, indeed from most everything, but not, his friends and neighbors observed, from Sir Walter Scott.

In fact it was a slander. Taft was not a forenoon drinker. If he was found to be imbibing in the morning, it was not from habit, but because he had forgotten to leave off the night before. So it was, no doubt, on this day, at ten-thirty, when Eli Adams knocked on the door of the room Taft used for a study. Too late.

"Eli!" cried Taft. "Eli, old sport. Come you in. Sit you down. Have an eye-opener with us."

Be careful, whispered Dangerfield. He stood in the shadow behind Taft. Mysteriously, he was attired in a fresh, well-pressed, white lab coat over a crisp blue shirt and a red polka-dot bow tie. A stethoscope hung around his neck, and the left breast pocket of his lab coat was embroidered: MASSACHUSETTS GENERAL HOSPITAL. He might have been a prosperous surgeon. Be careful, he murmured.

"Us?" Eli asked.

Taft pushed the Sir Walter's across the desk toward Eli, pushed a glass after it. "Water?" he asked.

"Nothing, thanks. Nothing at all. Well, maybe some coffee?"

"No coffee," said Taft. "Don't use it. Don't keep it in the house. That stuff is bad for you, Eli. Bad. Doctor told me once if he could get his patients to do one thing? For their health? Cut out coffee. That's right, coffee. Worse than booze, worse than the cigs, worse than dope. Worse than loose women —"

"Worse than work?"

"Well, well," said Taft. "But you get my point. Coffee. Stay clear of coffee, Eli. Sit."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.