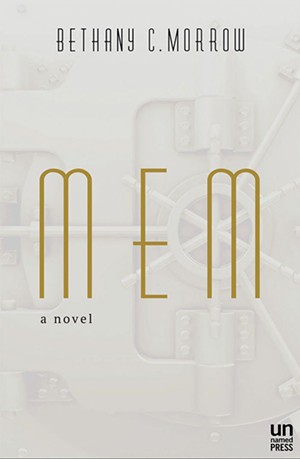

- Courtesy Of Elena Roussakis

- Bethany C. Morrow

"I am a memory. Now I suppose I'll live like one." So opens MEM, the slim debut novel by Bethany C. Morrow, which lures readers into the shimmering and complicated world of an alternate Montréal, circa 1925. In this bustling, quasi-European city in the throes of industrial advances — trains, planes and automobiles, as well as cinema and the prelude to cults of celebrity — we meet our narrator. She is the product of an entirely different kind of technological revolution: memory extraction.

Dolores Extract No. 1 is a fresh-faced, inquisitive 19-year-old. Early in the novel, she reveals that her self-given name is Elsie, after a character in the 1922 silent film The Toll of the Sea. In many ways, Elsie fits the character type of the "shopgirl" common in fiction of her era. She's an individuating young woman excitedly absorbing what the city has to offer — clothes, movies, a flat to call her own.

Instead of having blown in from the countryside or across the ocean, however, Elsie has been created through the marvels of science. Within an asylum-esque research facility called the Vault, scientists known as Bankers have developed a technique for removing unwanted memories from human minds. These pesky extracts are embodied as "Mems": specific memories uncannily given living human form, (partial) stories with literal legs. Each is legally the property of their "Source."

How, then, do memories live? As personified memories, can Mems lead any sort of independent existence? The struggle to answer this question propels Morrow's narrative, which launches at the moment when Elsie is recalled to the Vault for potential "reprinting" — that is, erasure and replacement with another memory. With this speculative scene set, Morrow, who lives near Plattsburgh, N.Y., uses her 175 pages to mine dense philosophical quandaries and offer layered social critiques with impressive economy.

Readers soon learn that Elsie enjoys an initial measure of autonomy not typical of Mems. Her life as "a real girl" results from her status as a scientific anomaly: Unlike other Mems, Elsie can create her own memories and, arguably, has consciousness.

- MEM by Bethany C. Morrow, Unnamed Press, 175 pages. $25.

What sometimes feels like a relentless onslaught of exposition becomes more tolerable as Elsie's character is fleshed out as someone who constantly finds new understanding. Aware of herself and the societal limitations that threaten her freedom, she becomes a scientist of both herself and Memhood at large. This evolution echoes the decolonizing impulse of auto-ethnography.

Ultimately, Morrow frames Elsie as her own most important discovery — or "epiphany," to use the language of the novel.

Though the author has created Elsie's Montréal as devoid of color-based racial hierarchy, one of MEM's most salient successes is its swift encapsulation of intersectionality, or the embodiment in one person of different identities and interrelated forms of social marginalization. From her liminal standpoint, she is a female without rights yet exalted by her culture; she exists between the human and inhuman, between subsidiary fragment and whole entity. Elsie becomes a vehicle for pointed and sometimes scathing social criticisms of ownership and control.

As a ward of the state, Elsie has keepers: the doting, fatherly "Professor" — the inventor of memory extraction and Elsie's creator — and his son, Harvey, for whom she develops romantic feelings. Morrow infuses these patriarchal relationships with a heartbreakingly real mixture of love and anger, though at times they come across as cloying.

"It was the first time I'd been lied to by a man," Elsie reflects after a conversation with Harvey. "What surprised me most was that while he was the one being dishonest, I somehow was the one made to feel small and uncertain."

While a degree of ferocity emanates from Morrow's narrative, she smartly resists a cookie-cutter plot of good-versus-bad. The sometimes-hapless scientists are, as in real life, entangled in their own battles with both wealthy patrons and the law, and the novel offers a smooth critique of new technology as a rich person's plaything.

The patrons — the "Sources" — are not presented as heartless monsters, however. Instead, they are achingly flawed humans doing what humans so often do: pursuing happiness for themselves and those around them, sometimes with tragic disregard for consequences.

The traumas that these Sources seek to extract from their brains are a mixed bag, only referenced in the briefest terms. They range from an adolescent's first realization of death to a mother's loss of a child to prolonged emotional abuse from an overbearing father. Not every extracted memory is a traumatic one. One elderly patroness gives life to a set of Mem triplets, the giggling, girlish "Keepsakes" meant for her grandchildren to inherit.

As Elsie grapples with her own fragile and unprecedented existence, she watches both Mems and Sources face various forms of death. Mems expire by literally fading in color and vibrancy. Sources become "fractured" by repeated memory extractions, losing their minds and becoming more and more like the Mems created in their image.

In giving memories human form, Morrow continues in the speculative tradition of works such as Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Blade Runner and Never Let Me Go. Her successful transposition of internet-age anxieties onto the then-jarring technological boom of the previous century is just one of the novel's many charms. With quick grace and rage, MEM offers a powerful argument that what makes us human is not just our memories — for better and for worse — but also our powers of self-determination.

From MEM:

Dolores Extract No. 2 was what a Mem is meant to be. She was my first real encounter with what I should have been. There was something missing from her eyes, some light or focus, so that even when she was looking at someone it was clear they weren't the true object of her gaze. She could walk and rest and eat — or not — and could be trained to do so at a certain time or to a certain distance or in a certain place, depending on instruction. That was one of two ways in which Mems before me amused society, by having routines imprinted on them despite being otherwise disengaged and unaware of the world around them. The other was the way they could be prompted to recall the memories they housed. Outside responding to that prompting, it was customary that Extract No. 2 spoke infrequently and then only according to the script of that August day in 1907.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.