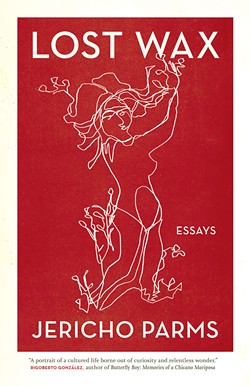

The title of Jericho Parms' book, Lost Wax, might confound anyone removed from the art world. A hundred pages into this debut collection of 18 lyrical personal essays, a reader may still wonder, What is this wax, why is it lost and will she ever get it back?

"'Lost wax' is a sculpture term," a landscape painter recently informed this reviewer. "It's something beautiful that's made and then lost in the process of making something else that's beautiful."

Parms invokes the term in an eponymous essay, noting that many ancient Egyptian and Grecian sculptors fashioned their gods and heroes using this technique. She writes, "The heat draws the melted wax from the form and it becomes 'lost,' drained from the mold, leaving a cavity for the molten bronze so that the image before us, the smooth limbs and androgynous angles, is a replica of what once was."

Eureka alert: Understanding the concept of lost wax will help inform a reader's appreciation of these segmented and numbered essays that explore ideas about art history, identity and geography.

Parms pours her life experiences into a unique mold in each essay — growing up in her biracial, loving but ultimately broken childhood home; college years fraught with unexpected losses and self-destructive behaviors; and her extensive travels in early adulthood in search of art, culture and meaning.

- Lost Wax: Essays by Jericho Parms. University of Georgia Press, 168 pages. $24.95.

Lost Wax is divided into four sections inspired by iconic sculptures: "Girl Looking at the Sole of her Foot," invokes Degas' famous dancer; "Daphne, Running" is a nod to classical figures housed at the Louvre; and "L'Eternelle idole" and "Caryatid Carrying Her Stone" refer to famous works by Rodin. Parms celebrates all of these at length, interspersing descriptions of their postures and contours with stories of (metaphorically and actually) traveling away from and back toward her New York City childhood.

The stasis of the sculptures serves as a counterpoint to her restlessness, for, as Parms attests, "the museum galleries are where I learned to reclaim myself. After years of incessant movement, I turn faithfully to the stone-solid silence of statuary, bow like a courtesan before its classical grace and refuse to feel alone."

Evidence of her attempts to outrun loneliness and confusion permeate these essays, as Parms ricochets geographically, intellectually and textually. "On Grazing," an essay from the third section, begins: "I used to collect things: rocks, minerals, artifacts and molds. That afternoon we ditched English lit and sociology to flee to the tracks where we hopped a train toward the southwest plains, only to hop off again somewhere — anywhere — to spoon beans from a can, sip whiskey from a canteen, and suckle and knead each other's flesh because we were sweethearts and the world was alive."

Parms acknowledges in another of the book's travel-inspired pieces, "I had scaled enough mountains to know never to doubt the challenge of a climb or the breathtaking reward. So I approached the mountain with its three stations of prayer blessed by an intrepid and earnest inquiry into the nature of pilgrimage." She could easily be advising readers to approach with the same attitude the switchbacking sentences that lead to her revelations.

Throughout this collection, Parms' prose resists overt, straightforward and full-blown autobiographical content; she prefers to evoke intuitive and unexpected links among a range of topics. Her essay "On Puddling" showcases the poignancy and meaning that can be achieved from a multifaceted approach to narrating the loss of a friend. In it, Parms introduces information about different species of butterflies, as well as Nabokov, the lepidopterist/novelist who flew into exile; the college classmate who collected and classified insect parts; and the wing-dust-like powders that she and this friend ingested. All of this comes in a story of that girl, who died from a fall.

Within the book, Parms cites such diverse sources as philosophers, artists and late-night Johnny Carson TV show episodes. In "Still Life With Chair," she integrates associations or references to the reality of an actual chair as compared to a representational chair in the paintings of van Gogh, Andrew Wyeth, Warhol and Kosuth. She includes the definition and etymology of the word "chair," Plato's theory of forms, excerpts from poems by Roethke and Neruda, and a mention of Thoreau's cabin (with three chairs).

Additionally, "Still Life" contains remembered scenes that took place in Manhattan and Colorado alongside imagined events at the 8th International Istanbul Biennial, in a ballroom with gold chandeliers and in a gymnasium filled with streamers. Amid this consideration is a narrative in which the author recounts how she fell in love with her college boyfriend and then learned of the sudden, shocking death of another classmate and friend.

The human body — its vulnerability, fragility and exquisite beauty — is perhaps the most obvious theme of Parms' collection. It's evident in the early pages, when her father's wrist smashing down on the table approximates a gavel, sounding the end of her parents' marriage. It echoes through the accidental deaths of friends and perhaps explains Parms' susceptibility to sculpture. "Every time I wander through a Greek and Roman sculpture court," she writes, "I want to be disassembled: to have my arms up to my shoulders fall off as I'm taken from Florence to Pompeii, or maybe end up at the Metropolitan or the Louvre having lost my legs. To be stolen, looted by strangers, and feel the tip of my nose, the cap of my knee chip and blow away."

Lost Wax shows us Parms' hard-won understanding that, at times, something beautiful must be forsaken for something even more beautiful.

From Lost Wax

What I remember most are the petri dishes she stole from the biology lab and kept in her dorm room. Like a curator, she filled them with insect parts: cicada wings, beetle backs, and fly legs — dried appendages like cellophane or tissue-paper jewels. She had worked out a system, her own web of wisdom. Sealing our hand-rolled cigarettes with our tongues and pinching the tail end, we laughed when she told us about Nabokov's cabinet of insect genitalia. We studied the specimens scattered around her dorm room as we experimented with a selection of pills and powders, which we wiped from our fingertips along our gums, hypothesizing the various effects: which would keep us from drying out, which would keep us up the longest with the gentle buzzing in our chests, which might let us fly.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.