- Greg Nesbit

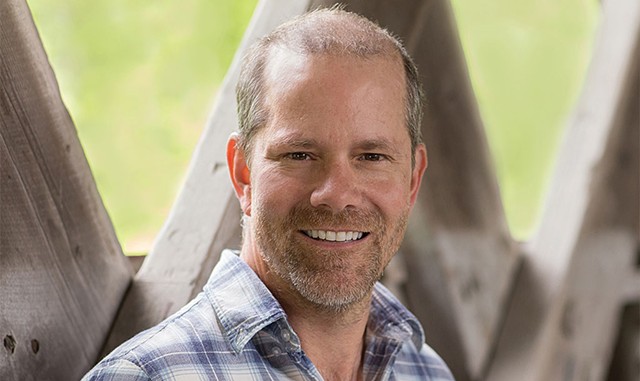

- Eric Rickstad

When Wayland Maynard is 8 years old, he comes home from school early with a stomachache and finds his dad sitting in the bedroom with a shotgun, his back to his son. One terrifying blast later, Wayland is fatherless. The only clue to his father's state of mind is a note the boy finds on the floor. It reads, "I am not who you think I am."

This event kicks off the action of southern Vermont author Eric Rickstad's sixth novel, a lean and mean thriller with a distinct gothic tinge. Like Rickstad's previous books, I Am Not Who You Think I Am is set locally — this time in the town of Shireburne, which seems a lot like Shelburne, down to the looming presence of the Vanders family — "the most revered and reviled name in town."

Much like the Vanderbilt Webbs at Shelburne Farms, the wealthy Vanderses built a lakeside estate and "ornamental farm" in their gilded age heyday, then "morphed their own Camelot into a nonprofit organization," Rickstad writes. There, one can only hope, the resemblances end, because Rickstad's fictional family of Vermont aristocrats gradually reveals a legacy worthy of spinner-rack gothic queen V.C. Andrews.

Rickstad has gained a following with gritty procedurals, such as the best-selling The Silent Girls, in which small-town cops chase killers. But his 2000 debut, Reap, about a Northeast Kingdom kid caught up in drug smuggling, was a more literary affair, a coming-of-age tale that evoked a darker Howard Frank Mosher.

In I Am Not Who You Think I Am, set mostly in 1984, Rickstad tells another coming-of-age story. This time, however, he juices it up with the fast pace and shocking twists of a thriller.

At 16, Wayland begins to suspect that his father's death was not what it appeared. A fragmented memory leads him to the hypothesis that the man he watched shoot himself on that terrible day was not, in fact, his father. Adding fuel to the fire is his recollection of a sinister encounter with a stranger at his father's barbershop (see below) shortly before the apparent suicide.

Is a mystery afoot in Shireburne? Or is Wayland desperate for any excuse to believe that his beloved father is still alive?

From page one, Rickstad uses a framing device to establish Wayland as a potentially unreliable narrator. The novel opens with a letter dated 2020 from the Shireburne chief of police, who describes the story we're about to read as a handwritten manuscript he received in the mail from "a former Shireburne citizen" who was presumed dead in a fire.

Addressed to the entire town, the manuscript is Wayland's first-person narrative, which starts on a confrontational note. He promises a tale that will shock residents into remembering a kid who was always overlooked — "the ghost boy slouched in the corner and peering out with anxious eyes." The grown Wayland relates a story of adolescent angst and amateur detective work that reads like a young-adult novel penned by Stephen King.

- Courtesy

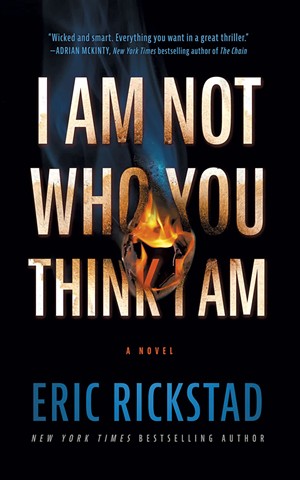

- I Am Not Who You Think I Am by Eric Rickstad, Blackstone Publishing, 240 pages. $25.99.

With the help of his gal pal and crush, Juliette, teenage Wayland combs the local library and town clerk's office for clues to the meaning of his father's cryptic note. There's a corny (and nostalgia-inducing) Nancy Drew quality to their low-tech sleuthing. But what Wayland doesn't tell Juliette is that he's haunted by a vision he spied in a window on the Vanders estate: a man and woman engaged in what appeared to be a sexual act, the woman wearing "a masquerade mask of pink plumage."

Rickstad has crafted a tale twisty enough to foil even mystery fans. While we may guess at the gist of the truth, we aren't likely to pinpoint its particulars until they're revealed in the denouement. And fans of the gothic will find those particulars satisfyingly baroque.

This is no slow-burn, Shirley Jackson-style gothic, either. As a narrator, Wayland is prone to gleefully grotesque description that puts him firmly in the King universe. Of his father's death, he writes, "I lifted my eyes to the ceiling, to see scarlet fireworks that would have been spectacular had they not been made of gore."

Wayland's descriptions of his single mother's down-at-the-heels household are nearly as stomach-turning, if more mundane: "dishes barnacled with crusted food [...] bales of soiled laundry, the stench of [the dog] Molly's menstruation, and the burned, greasy odor of the TV dinners." To escape the ugliness of this day-to-day life, Wayland is more than willing to confront the ornate horrors that lurk on the Vanders estate.

But will the reader take that journey with him? While Wayland's attitude is realistic enough for a teenage boy (or for an embittered adult recalling his teen years), Rickstad strikes the same notes of rage and self-pity so often that they become a little monotonous. Wayland seems not to have had a moment of genuine enjoyment since his father died. His clashes with his sister's no-good boyfriend and his jealousy of his jock friend — whom he believes is his rival for Juliette — grow tiresome.

Ideally, a psychological thriller tempts readers to venture into the depths of a disturbed mind and follow its twisted logic, reminding us of how close we all might be to the edge. I Am Not Who You Think I Am doesn't entirely deliver on the complexity of character development that its title promises. Instead of getting deeper into Wayland's head, we often watch him going in circles, both in his detective work and in his personal life. As a result, we may find ourselves taking a distance from him and viewing the horrific conclusion of his quest with a touch of amusement and schadenfreude.

After all, Wayland has been warned several times not to "wreck your future trying to understand the past," as one character portentously puts it. It's a scenario as old as Oedipus Rex, and Rickstad doesn't quite succeed in bringing those hoary tropes back to life. Nonetheless, the story's irresistible hook and complex unfolding are likely to keep readers engaged to the last page.

From I Am Not Who You Think I Am

The shop door opened. My father's shears nicked my ear. I yelped. Blood trickled from my notched flesh. I pinched the lobe as blood leaked down my fingers and wrist. My father didn't notice. His eyes were locked on the figure in the doorway.

Dead leaves danced around the stranger's feet. I felt a chill from the air that carried the tang of autumnal decay.

The stranger unsnapped the top button at the throat of his long black coat, the collar pulled tight to his neck. The wind vibrated a single errant strand of his long mane of black hair, which was swept back in a wave that appeared poised to crash upon his gleaming forehead. He looked to be older than my father by a good three decades. His facial features were sharp and long and narrow, as if rendered by the same hands that wrought the Easter Island colossi. His eyes were dark and imperious. In one hand he carried a black leather bag. He held my father's gaze without moving or making a sound. They clearly knew each other; my father's eyes betrayed recognition and, I thought, great unease.

The stranger shut the door. Blood tracked along the edge of my jaw and down my neck.

"A word," the stranger said, entirely unaware of, or perhaps just unconcerned with, my presence.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.