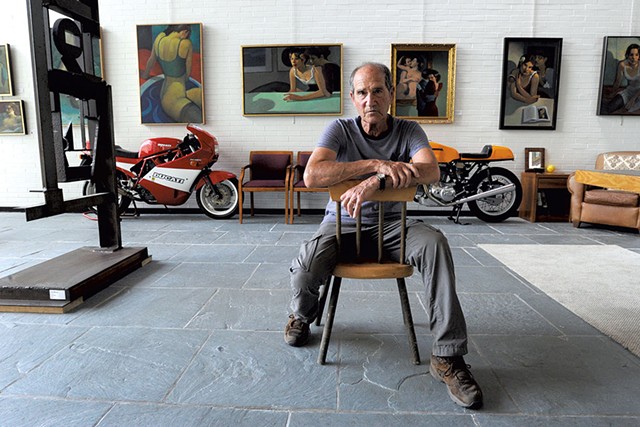

- Jeb Wallace-brodeur

- Billy Brauer at the Bundy Modern

"Dumb luck" brought Billy Brauer to Vermont, as he tells it. In 1968, as a young man, he came up from New York City, accompanying his cousin to a New Year's party. "[Vermont] was deserted," he said. "I thought, This is terrific." Three years later, Brauer bought his Warren house for "next to nothing," and he's been living, working and teaching in the Mad River Valley ever since.

Just a few miles from Brauer's studio, at the Bundy Modern in Waitsfield, the exhibition "Billy Brauer: 50-Year Retrospective" celebrates the artist's career with a selection of 30-some oil paintings, as well as early etchings and studies in oil and charcoal. Brauer is known for his paintings of erotically charged female figures — particularly his highly successful, commercially reproduced series of dancers. Accordingly, most of the paintings on view at the Bundy depict women alone or in pairs. The exhibition includes several self-portraits, too; one pencil drawing was made when the artist was just 10 years old.

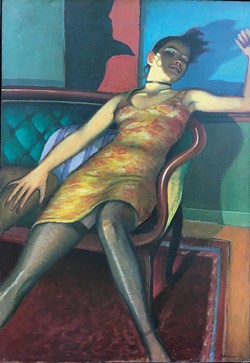

Most of Brauer's female subjects are sultry, lithe and conventionally beautiful, often shown in mysterious fragments and reflections. They are frequently engaged with an unseen entity; sometimes their bodies are presented as aspects of landscape. Mythical characters appear regularly, such as Echo, Thisbe and Europa. Art historical factors are evident in both style and content — specifically, the single light source favored during the Renaissance and the rich palette.

"I'd do these paintings that I thought were like Renaissance paintings," Brauer said. "But with my training as an illustrator, I'm much more of a designer. I got a chance to combine the two."

By contrast, some of Brauer's less opulent oil studies feature more ordinary bodies. His etchings sometimes gently gesture toward the grotesque with figures such as "Sophia," a snake lady; and carnival performers. Brauer noted that when he works from his imagination, as he does in his paintings, the piece "can get more weird."

Many of the paintings at the Bundy are on loan from local collectors. Bundy co-owner June Anderson reported a major spike in gallery attendance, which she attributed to Brauer's hometown popularity and his national reputation as a commercial artist. In previous years, Brauer was represented primarily by the Chase Young Gallery in Boston and the Patricia Rovzar Gallery in Seattle.

Brauer is 78 but hardly looks it; he's fit, an avid golfer. For the past 40 years, he has taught Thursday night drawing classes in Montpelier, making the 50-mile round trip regardless of weather. Only recently did he get his first cellphone — but luckily, he said, he's never needed one to call a late-night tow truck.

In conversation, Brauer is as likely to point out perceived flaws as successes in his own paintings. With his unassuming nature, it's easy to see why generations of students have sought him out as a teacher. Brauer recently spoke with Seven Days at the Bundy about his work and career trajectory.

SEVEN DAYS: Can you talk about your arrival in Vermont?

BILLY BRAUER: I didn't know people like this existed. [Coming here] was the first time I ran into people who had some sort of ecological sense. The locals were so accepting. I was this hippie from New York City, and, considering what we all looked like, I can't believe that they were so nice to us. So welcoming and helpful — no wise-guy stuff.

When I came here, I was a subsistence farmer. I was married to a weaver. I raised sheep. I heated with wood until 20 years ago. I always maintain that if you don't have any money in New York City, you're poor. If you don't have any money here, all it means is you have to live a different kind of life. Do a lot of stuff yourself. But you aren't poor. Actually, Vermonters used to say that to me: "We never had any money, but we didn't know we were poor until you guys came."

SD: You've said you knew from a fairly young age that you were going to be an artist. What did that look like for you?

- "Erotic Dreams of Lenore"

BB: I don't know if I knew it, but it was what I could do. You tend to do what you do best. [There was] no encouragement from my parents at all. I finally went to art school, which is all I wanted to do. Then it was great.

I was just talking to this couple from Ottawa about Norman Rockwell. I told them that was the only thing I had in the house growing up, the Saturday Evening Post. I couldn't wait to see the illustrations. When I found out Rockwell was from here, that was even more amazing.

I went to the School of Visual Arts in New York City. I became a printmaker first — well, I was an illustrator. Then I got involved in printmaking, doing etchings. A lot of these [at the Bundy] are from the '70s.

As an illustrator, I did a lot of album covers, a lot of sports stuff. I did work for Golf Digest — instructional drawings, golf paintings. But then I got hooked up with Chase [Young] Gallery in Boston. That was my first big move. I bet I was with them for 10, 15 years. Then I went to Seattle. This woman called me up and said, "I can sell your work." I said, "I've heard that before." She said, "Send me the paintings, and I'm gonna sell them." And she did. So I did shows with her for 10, 12 years. Consequently, I'd work from show to show. That's like [making] a painting every two weeks.

What happened was, this dance piece ["Night Dance"] was the precursor to a whole bunch of other dance paintings. I had a show at Chase, and I'd say, out of 20 paintings, 10 of them were these ballroom-dance things. And they just, phhht, disappeared the first night. I did that for maybe two years, and then I didn't want to be the guy who did the dance paintings anymore.

But some company out in San Francisco wanted to do prints. I'm a printmaker — a real printmaker. To me, reproductions are not prints. I don't care if you sign them and say you number them — that's bullshit, they're not prints. So I said, "You put type on it and I'll do it, and call them posters." And that's what we did.

That was a bonanza. I had no idea. I thought it would be fun to have a lot of posters hanging around. [But] my first royalty check, I thought, This must be a mistake. [Because it was such an unexpectedly large sum.] What finally happened was, big companies like Target bought a whole bunch of them. The posters are still going. Every once in a while, I still get a check.

SD: What do you think accounts for the works' broad appeal?

BB: "Tango" is the only [original painting] left [of those that became posters]. All of them were really beautiful ... They gave me a chance to [paint] what I like, which is women's backs. I always had the guy pretty much hidden. You never see his face — he's just presenting her. They're sensual, not sexy. Women like them, and men like them. They were big.

SD: Have you always focused on women and the female form?

BB: Yes. Pretty much so.

I sold "Dancing With Bronzino" to someone here in the valley. Her housecleaner saw it and went to Wendy — the woman who is now my wife — and said, "There's this painting that looks just like you. Did you pose for it?" She said no.

I was in the middle of a painting, and I wanted someone who was tall with a long back, and someone suggested Wendy. So she came and posed for me, and we wound up going to the Mozart Festival; five years later we got married. That was 17 years ago, something like that.

Then people said all the other [subjects] looked like Wendy, which they probably do. This was before I knew her. I call it the "Cinderella complex" — I already had the glass slipper, and I was looking [for the owner]. That's pretty much the way it worked out.

SD: Do you have a favorite or most-returned-to historical or mythical female figure?

BB: I've done so many paintings of Thisbe. She fell in love with a crack in the wall. Pyramus is on the other side. Thisbe's great for me. The woman and the wall and something on the other side of it — that's all the stuff I like to do. That's the best part about mythology, if you're a representational painter. I don't consider myself a realistic painter. If I have to design something, I can have something floating and get away with it if it's in mythology. Otherwise, you can't.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.