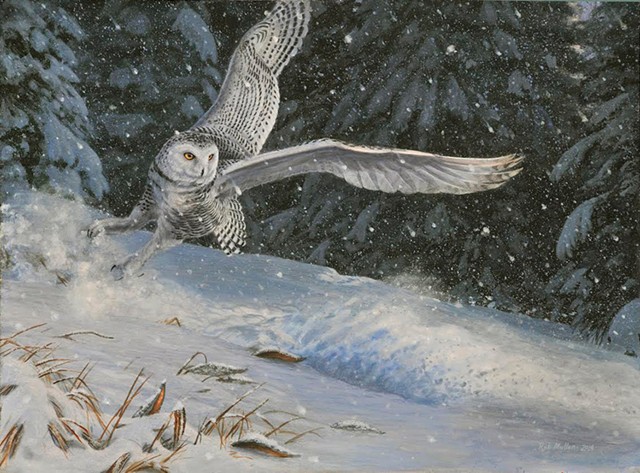

- "Snow Squall"

Vermont is teeming with artists who paint pets, farm animals and critters from the woods. But there may be only one who has painted a charging bear — that is, the bear that charged him on a remote river in Alaska. That would be West Bolton artist Rob Mullen.

The Vermont native earned a biology degree from the University of Vermont in 1978. He worked as an illustrator and advertising artist in New York City ("the hands for the Mad Men," as he puts it). At the age of 30, "to stave off getting old and boring," he writes, Mullen organized a canoe trip in northern Canada. It was the beginning of a lifelong engagement with wilderness, conservation and art.

Over the past couple of decades — having left advertising and returned to Vermont — Mullen has developed a reputation as a wildlife and wilderness artist. Now 59, he's represented by Robert Paul Galleries in Stowe.

In 2005, Mullen founded WREAF — the Wilderness River Expedition Art Fellowship — which offers nature artists immersion experiences in the wilds. (In 2013, it was adopted as a program of the Vermont-based Center for Circumpolar Studies.) "WREAF crews live their art on extended and self-supported river expeditions in some of the most rugged and remote regions of North America," he writes. The program's focus is the boreal forest, the northern swath of heavily treed land that covers 60 percent of the landmass of Canada alone. Mullen most certainly walks the talk.

The name of his website, Paint N Paddle Studio, may sound placid, but it's misleading. You need only click on "Expeditions" to find evidence of Mullen's multiple trips into uninhabited corners of Alaska and northern Canada. It's easy to get pulled into his riveting accounts of these challenging and often-dangerous adventures.

That grizzly attack happened during a solo journey in 2013, the second of three trips whose goal was to circumnavigate Alaska's western Brooks Range. Mullen had endured grueling climbs, drenching rains and a nearly impenetrable alder thicket — not to mention several bear encounters — by the time he managed to aim his canoe down the beautiful Reed River. Moments later, a grizzly charged out of the blue — less than 25 feet away. Mullen describes the moment on his website:

With no pause, he leapt into the river and charged straight at me along the shoal. I responded with dumb shock and frantic denial. As my world descended into surreal slow motion, a strange steely calm arose, brushed aside my stubborn disbelief and crushed my spasms of ballooning panic. The canoe spun to the left and the next thing I knew I was intently focused on pulling the carbine clear without the sight hood catching on the pack.

Mullen pointed his rifle to the side of the bear's left ear and fired. Luckily for him, the gunshot achieved his goal. The bear paused, gave Mullen a "dirty look," he says, and began to swim away. But not before the artist, with incredible presence of mind, grabbed his camera and videotaped his attacker.

That's how Mullen was able to paint the mean-faced bear in "Alaska Cold Rush" with such chilling accuracy. During a visit to his home studio, he displays the painting and points to a small rock on the bank behind the bear's head. "That's what I aimed for," he says.

Some might have aimed to kill, but Mullen's respect for fellow creatures runs too deep. "As fellow Earthlings, their differences and similarities to us are endlessly fascinating," he writes. "Face to face with a bear or caribou out on the windswept tundra of Labrador (where they typically have no knowledge or fear of humans), or a salamander in the pond behind our house, I get a tangible sense of being in the presence of an almost alien stranger whose perception of the world is profoundly different from ours, but no less valid."

- "Alaska Cold Rush"

In addition to capturing creatures on his treks — not only bears but caribou, wolves, whales, fish and numerous birds — Mullen says he particularly likes to paint rocks and water. He's good at it. But the technical skill of his paintings is only part of their appeal; the images also serve as reminders that millions of acres of unspoiled wilderness remain in North America.

Mullen's longtime focus on the boreal forest has led to collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History, as well as with the Canadian Boreal Initiative. He's worked with a Smithsonian director to develop an extensive wilderness exhibit for that institution. That effort has been stymied again and again, but Mullen remains confident that the exhibit will happen eventually.

Meantime, he's working on a book featuring wilderness, wildlife and landscape artwork by some 30 artists. Its working title borrows from Tolkien's Middle-earth: Boreal Wilderland.

Concurrently, Mullen is engaged with a conservation controversy in his own back yard: trapping at Preston Pond. Extending onto his family's property, the ancient body of water is "the central jewel," Mullen says, of the Bolton Town Forest, which in turn is a key property of the Chittenden County Upland Conservation Project. Mullen insists that traps set just yards away from popular hiking trails present a danger to humans and their dogs as well as to the forest's wildlife.

His passion for local land, its issues and its creatures has presented a paradoxical challenge to this seasoned outdoorsman. "I am facing my fear of painting home," Mullen says. "Getting it right has always been intimidating."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.