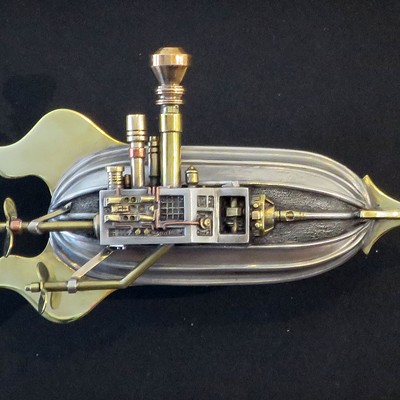

Perhaps you've seen him around Burlington: a stocky guy with neatly trimmed beard, often wearing a black top hat and suspenders over a button-down shirt and too-short black pants. Handmade metal art objects decorate his quirky attire: gleaming cuff links in bronze and steel; and an inch-long bronze and pewter pin resembling a steam-powered blimp with minute gears and a propeller that spins.

The figure, and the metal artist, is Mark Eliot Schwabe.

"He's his own best advertiser," said Kory Rogers with an admiring chuckle in a phone call. The Shelburne Museum design curator included Schwabe's metal airships and other figurines in the 2012 show "Time Machines: Robots, Rockets and Steampunk." Rogers called them "beautifully engineered."

Now 68, Schwabe started working in metal at age 14. Since then he has run the gamut of possibilities in his field, from making precious-metal jewelry for Cartier to fashioning licensed Star Wars models in pewter to creating large sculptures in steel, bronze and concrete. A series of his sculptures is currently on display at the S.P.A.C.E. Gallery on Pine Street in Burlington.

Schwabe titled the show "Ignecia," a word he coined based on "igneous," a term referring to volcanic rock. The title is also the name of the imaginary steel-and-concrete landscape featured in these 20-odd wall-hung and pedestal-mounted sculptures and accompanying black-and-white photos.

Schwabe calls the show a "morality tale" and has marked its narrative direction with arrows in red tape on the floor. The characters include representatives of Ignecia's sparse population, cast in bronze. "Innocents" are mammalian creatures, seen in watchful poses, that possess family values, the artist said. "Evil Doers" are havoc-wreaking quadrupeds that look like something out of a Tolkien fantasy.

The show culminates in a foot-high bronze model of Schwabe himself: a bearded, potbellied "Artist Champion." Taking a heroic stance, cape swishing and sword brandished, the artist has come to protect and defend the innocents.

That gesture illustrates Schwabe's delight in role-playing and stories. Dyslexia prevents him from "reading a book cover to cover," he said, but that hardly checks his imagination. In 2008, Schwabe joined the fantasy-art subculture called steampunk; its adherents dress as occupants of an imagined futuristic world that never moved beyond Victorian steam power. Tapping his temple, the artist noted, "There's no shortage of stories up here."

Schwabe got his start as a metal artisan with the family jewelry business. His father, the son of German immigrants, left school at 16 to apprentice with a platinum smith. After World War II, he adopted the new rubber-mold technology and made models for the costume jewelry industry. Soon the elder Schwabe was creating his own precious-metal jewelry and sculptures in the basement of his Long Island home. His wife ran the Manhattan showroom. Cartier was their biggest client.

Mark Schwabe, who was the family's diamond courier, began helping his father make these labor-intensive pieces the summer he turned 14. He absorbed every step of the process: making models and molds, lost-wax casting, assembling, polishing. Recently, at his South Burlington home, Schwabe retrieved miniature statuary from those days: intricately detailed knights on horseback attacking dragons no more than three inches high.

Schwabe studied psychology in college and worked for his father during breaks, then went on to earn a master's and an MFA in sculpture at the state universities of New York at Albany and New Paltz, respectively. His subsequent jobs in the Albany area — teaching at local colleges, heading a county arts council, supervising a jewelry factory — helped support his love of metal sculpting.

"It's an addiction," Schwabe explained. "I can't not make things."

- Matthew Thorsen

- Mark Eliot Schwabe in his studio

As a graduate student at Albany, he assisted Richard Stankiewicz, who had pioneered welded-steel sculpture in the 1950s and was one of the country's leading metal sculptors by the early '70s. Stankiewicz's found-metal works are held in major museums in New York and Washington, D.C.

Influenced by his teacher, Schwabe began creating large abstract sculptures. Vermont collector Mark Waskow, who owns more than 20 of Schwabe's pieces, has a seven-foot-tall steel-and-bronze work from this period.

"It's pretty spectacular," Waskow said in a phone call. "It's over human scale. If you're in the presence of its orbit, you get sucked in."

Waskow also owns many of Schwabe's "wearable sculptures," which include his steampunk jewelry. "There's a lot of really important small metal sculpture that happens to be called jewelry," he commented.

Schwabe has made several lines of small but exquisite sculptural work. "The Albany Collection" was a jewelry series modeled on architectural details in the capital city that caught Schwabe's eye. The artist retrieved a photo album and paged through snapshots he took while designing the line for an Albany jeweler, such as a gargoyle with twisted limbs that inspired a brooch.

Even Schwabe's commercial trinkets are small wonders. Among these are inches-long pewter "Star Trek" and Star Wars spaceships, freelance work he did for a pewter giftware company in Rhode Island. A highly detailed X-wing starfighter and Millennium Falcon grace his living room curio cabinet.

Schwabe created his larger works in Grafton, N.Y., where he had a spacious studio for 15 years. He gave up that space when he moved to Vermont in 2000 — a dream he'd had since 1970, he said. Schwabe showed some works at outdoor venues such as the Inn at Round Barn Farm in Waitsfield and Moosewalk Studios & Gallery in Warren, and he put others in storage.

His work recently caught the eye of Wendell and June Anderson, who have booked Schwabe for a June group show at their gallery-cum-home, the Bundy Modern, in Waitsfield. The midcentury Bundy's grounds used to be filled with modernist sculpture. Wendell said the "geometry mixed with the organic nature" of Schwabe's work appealed to the couple.

Schwabe moved into his current studio in the S.P.A.C.E. Gallery in 2009, at the start of his steampunk phase. He was one of the first applicants for the then-new venue, according to owner Christy Mitchell, who called Schwabe's work "subversive and fringe."

His nine-foot-square studio has a built-in, wraparound workspace and is packed to the ceiling with hundreds of metalworking tools that the artist made himself.

Schwabe didn't fabricate the works in "Ignecia" here — the largest is a garden sculpture measuring 27 by 20 by 18 inches. Made in the 1980s, those were first shown in 1988 in an Albany gallery and have not been exhibited as a group since. Schwabe had to pull them — minus a few that sold — from multiple storage places. "I have a storage problem, plain and simple," he declared.

The diminutive workspace accounts for the scale of his current work: the wearable sculptures, metal frames for wall hanging and "Markie Moose" pewter pins that he sells on Etsy. Schwabe also fabricates framable vintage cars, including a three-inch-long 1948 Chevy and similarly sized '62 Corvette. He corrals the tiny parts in the plastic caps of peanut-butter jars on his work table.

"He is toiling in a small studio in northern Vermont, relatively unknown, which is really a crime," commented Waskow. "If you look at a lot of metal sculpture, you can tell which ones are well-made." Schwabe's are.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.