- Chelsea Edgar

- Joan Morris

If you've been to a Broadway production of The Lion King, you've seen Joan Morris' textiles. Her hand-dyed fabrics transform the ensemble cast in Act 2 — during the "Can You Feel the Love Tonight?" scene — into a lush, fantastical rainforest. Those costumes began life far from the stages of Manhattan — in Morris' studio in Hartford, where she has lived and worked for the past 35 years.

Over the decades, Morris has taught and exhibited in places as far-flung as Japan and the Republic of Georgia. But you don't need to buy a plane ticket — or even schlep down to New York — to catch a glimpse of her work. Since 1988, she has been the master dyer in the Dartmouth College theater department, creating one-of-a-kind pieces for student productions.

Morris specializes in shaped-resist dyeing, a technique that involves stitching, bunching or otherwise contorting fabric to control the spread of pigment, which can produce a mind-boggling array of patterns and effects. She also co-holds the patent on a process for applying precious metals to fabrics. "No one else had been able to figure it out for thousands of years," she quipped.

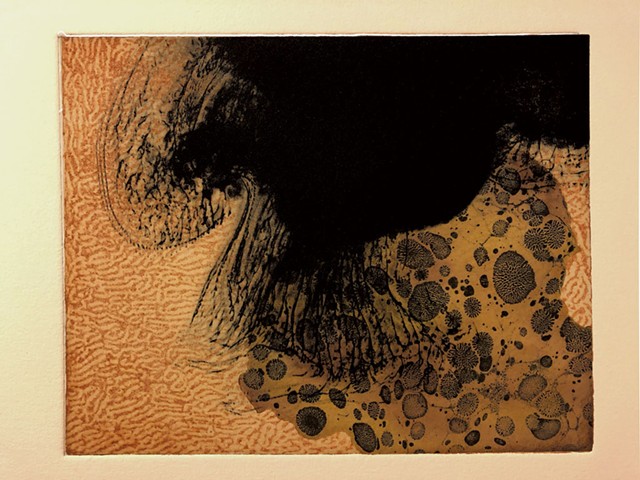

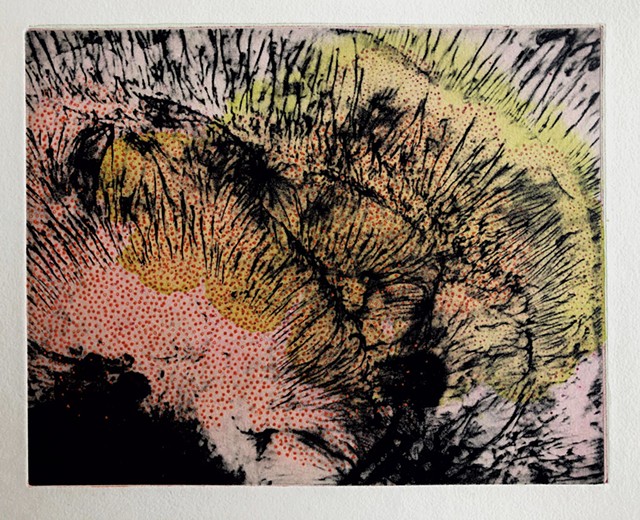

Several years ago, Morris said, she felt an inexplicable compulsion to begin making prints, which ultimately led her to the work currently on view at Two Rivers Printmaking Studio in White River Junction. Titled "You Are the Music," the show offers a glimpse into Morris' process — a palimpsestic layering of textures, colors and materials.

These prints don't represent a departure from her textile work so much as an evolution, the renaissance of a practice she began in high school. Decades later, the work is enriched by a lifetime of experience.

Seven Days talked with Morris about her latest work, the importance of saying yes, and how hitchhiking to use Dartmouth's showers might have led to an international career in textiles.

You've spent most of your career working with textiles for theater. What moved you to start making prints?

Three years ago, a very old, very important friend moved away. I was unexpectedly flabbergasted, and then a few other things happened afterward that caused this opening in me — a catharsis, really. In response to that, I found myself creating these automatic drawings with ink in water, which were impermanent and so amazing to me that I started taking photos of them.

I had already been making prints for a couple years, and I decided to delve into a series based on those captures. The title of the exhibit comes from a line from T.S. Eliot's "Four Quartets": "...you are the music. / While the music lasts." It's about temporality, a meditation on time. Pretty much everything I do is about temporality, about trying to capture something that's moving past us.

- Courtesy Photo

- Untitled work by Joan Morris

Something about these prints seems both totally spontaneous and also incredibly, painstakingly controlled. How do you achieve that effect?

The way I work, as an autodidact, is that I know what I want or need to make, and then I learn how to make it. That's how you learn in theater: Basically, if you don't know how to do something, you don't have very long to figure it out, or else you're probably not going to have a job. So I started by picturing what I wanted the images to look like, and then I figured out how to do it.

I knew when I was making these images that I didn't want them to be just black and white; I wanted to introduce other textures. I used a technique called chine-collé, which is a way of taking a very fine, absorbent Japanese paper called kitakata and wetting it, putting it on an inked plate, and then putting rice flour on top of the paper, which absorbs the moisture and becomes a paste. Then I put my printmaking paper over the whole thing. When I peel that off, the kitakata has glued itself to the wet printmaking paper, and the intaglio has printed onto the kitakata.

You never went to formal art school; who or what have been your greatest teachers?

I went to a public high school in Long Island with an incredible art program: I had a printmaking teacher, a drawing teacher, a painting teacher and a sculpting teacher. On my own, I was sewing, weaving, gathering plants for dyes, batiking, everything. I learned how to sew and handle different textiles from my mother, probably as a way of being with her. She was a dressmaker, and her mother was a dressmaker, so it was passed down. It's a great way to learn, being at the knee of someone older than you; you get to be the beneficiary of tacit muscle memory.

The shaped-resist techniques that I use are probably an extrapolation of something that began in eighth-century India or China or Japan. The textile world is an open-knowledge system; traditions constantly evolve, because if they were frozen in time, they wouldn't survive. So shaped-resist dyeing speaks to me as something that can be unpacked and unpacked and unpacked. Really, all the things I make are thousands of years old.

How did you end up working at Dartmouth? I'm assuming most colleges don't have a "master dyer" staff position.

After I graduated from high school, I went to community college in Long Island for about a minute. When I turned 18, I moved to Vermont to be part of a meditation commune in Fayston. My boyfriend at the time was part of that commune, so I got myself up to Vermont in my ancient Volkswagen, with all my plants, and he broke up with me before I'd even unpacked my car. I was heartbroken, and that caused a huge cascade of events that moved me forward in my life.

Eventually, I left the Fayston commune and moved to another one in Perkinsville. We had no running water or electricity, so once a week I would hitchhike by myself to Dartmouth to take a shower.

Meanwhile, I was still spinning, plant dyeing and weaving on my own, but I didn't know how to make a dress from a picture. Then I learned that there was a class in pattern making and draping in the Dartmouth College theater department, and the instructor let me audit. At the end, she asked me if I wanted a job in the costume shop. That was 35 years ago.

Now, I work three days a week and have the other four days for my own work, which has been an unbelievable gift. Talent isn't the biggest thing in the whole constellation — timing and connectivity both matter a lot in how you make a career.

- Courtesy Photo

- Untitled work by Joan Morris

Speaking of connectivity, how the hell does one end up making textiles for Julie Taymor's Broadway production of The Lion King?

At Dartmouth, I was working with this amazing scenic designer and professor, Georgi Aleksi-Meskhishvili. He had worked with Julie Taymor on Salome in St. Petersburg, Russia, and he really liked my work. At one point, Julie asked him if he knew "a dyer of special effects," and he recommended me. So Julie and I ended up meeting in New York, and she showed me her renderings of these beautiful, elaborate jungle costumes for a scene in The Lion King — Act 2, Scene 8, "Can You Feel the Love Tonight?" She asked me, "Do you think you can do this?" And I said, "Yes, I do."

That's how it's always gone for me: I say yes to the gig, and then I figure it out.

For the next few months, I worked on the textiles every night — basically pulling all-nighters — and FedExed designs every day. Julie would send the fabric sample back, cut in half so she could keep her own record of what we were working on, with notes.

The thing that I do in textiles is really this marriage of determinacy, intention and indeterminacy, by which I mean the unseen elements of the dynamic outer world — heat, concentrations of materials, fluid dynamics, chemistry. I'm not chagrined when things don't work; I learn from it.

So we went back and forth and developed this vocabulary of design, and once we'd arrived at where she wanted to be, she had me create the textiles for the costumes in that scene. I thought I would only be doing it once; then The Lion King ran for 22 years, and it's still running.

When you're working on something that big, how does it feel to come to an end?

After I finished the work for the first production, I thought, Great! I can finally get around to painting my house. And then one day, I was in my studio in Hartford, and my fax machine started spewing out papers about all these other productions that were going to open all over the country. All of which is to say that I don't plan too far ahead, because I know that everything has its own life; everything takes the time it takes.

I always try to live the way I lived when I was young — resourcefully, organically, everything pieced together.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.