- Courtesy Of Middlebury College Museum Of Art

- Bauhaus workshop installation built by Ken Pohlman

Last year, museums around the world mounted special exhibitions marking the centennial of the Bauhaus — an experimental and profoundly influential school of art, design and architecture founded in Germany in 1919.

In fall 2019, Middlebury College assistant professor Erin Sassin offered a class in the history of art and architecture department called "Exhibiting the Bauhaus," in which 17 students plotted their own exhibit about the famous school. Their focus was its original intent: experimental learning, unfettered by hierarchical distinctions between craft and art.

Besides learning about the Bauhaus' 14-year existence before it closed in 1933 under pressure from the Nazis, Sassin's students studied its curriculum, trying out creative prompts devised by its teachers a century ago. And they discussed how to engage present-day museumgoers in similarly interactive modes of learning.

The result of their work is the imaginative exhibit "Weimar, Dessau, Berlin: The Bauhaus as School and Laboratory," which opened at the Middlebury College Museum of Art last Friday. A reception this week features a talk by Sassin and a performance of dance and music by Middlebury faculty members Laurel Jenkins and Matthew Evan Taylor, respectively.

The show's cocurators were Sassin and Sarah Briggs, a graduate fellow of the Serge and Vally Sabarsky Foundation in New York, which loaned many of the works. They helped the students devise the curatorial narrative and drafted wall texts, along with other aspects of the show.

That narrative focuses on the radical ways in which the Bauhaus fostered artistic innovation, and how these changed under different directors and as the school moved from Weimar (1919-25) to Dessau (1925-32) to Berlin for the last year of its existence.

As its subtitle suggests, the exhibition is organized similarly to the Bauhaus' workshops and classes, with sections on printmaking, interior furnishings, life drawing and sculpture, theater, music, and surface form. On display are 52 works — prints, lithographs, photographs, sculptures, posters, furniture and more — produced by both "apprentices" and "masters" — the Bauhaus lingo for students and professors. Other than one book from Middlebury's collection, all of the works are loaned.

Wall text notes that the Bauhaus had no architecture workshop, despite its legacy being most closely associated with architecture. Instead, Bauhaus students gained experience in the field through the commissions and teaching of the directors — Walter Gropius, Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe — all of whom were practicing architects.

In that spirit, the center of the Middlebury gallery features an architectural installation: an open-structure "workshop" room built by exhibition designer Ken Pohlman. Its main wall evokes the structural grid of the glass curtain wall that Gropius designed for the studio and workshop building of his Dessau campus. That building, completed in 1926, became one of the Bauhaus' most recognizable visual signifiers.

The workshop room is dedicated to the Bauhaus' half-year Preliminary Course, required of all its students. Lithographs by its master teachers, Johannes Itten, László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers, hang there.

Equally compelling are the student-created responses in paper and other materials to the German teachers' prompts. A central worktable invites visitors to make their own responses, and similar participatory prompts appear below the wall texts introducing each section of the exhibition. In the theater and music section, for example, visitors are invited to "Make a movement with your body (big or small). Draw the shape or shapes of that movement."

- Courtesy Of Middlebury College Museum Of Art

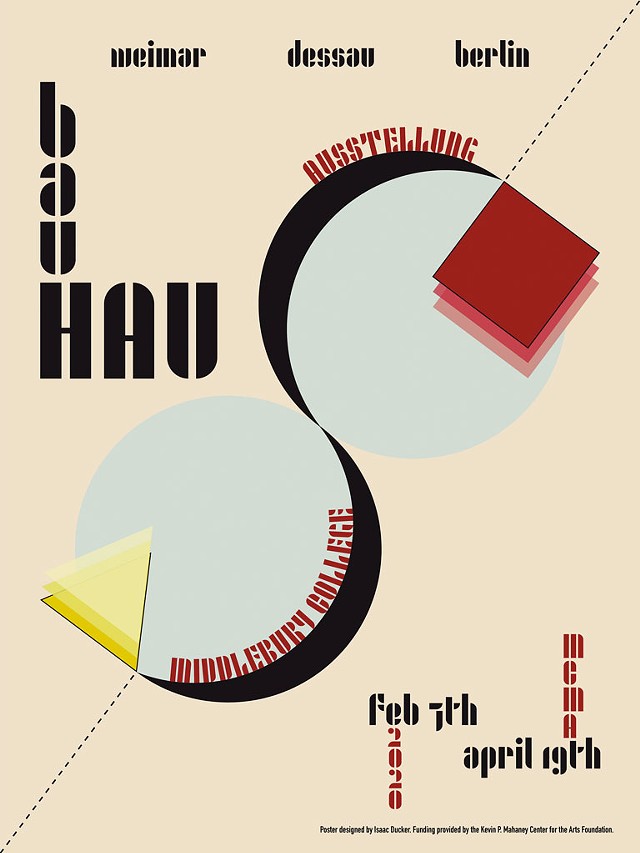

- Postcard designed by Middlebury College student Isaac Ducker

Among the Middlebury students' other original creations on view are a virtual-reality tour of the Dessau campus (screening on a video loop) and a row of postcards designed to promote this very exhibit. The latter were created in the spirit of the Bauhaus' two-month Ausstellung, or international exhibit, which drew thousands of visitors in 1923.

At a side station labeled "Play. Experiment. Create. Discover," students have equipped an activity table with replicas they made of designer Alma Siedhoff-Buscher's 1923 set of colorful wooden sailboat building blocks and sculptor Josef Hartwig's 1924 wooden chess set. The geometric shapes of the latter are an elemental demonstration of form following function.

Play was a central part of Bauhaus student life, an aspect captured in two photographs in the Middlebury exhibit. One is by Bauhaus student T. Lux Feininger, whose father, Lyonel, was master of the printmaking workshop. It shows three raucous student musicians horsing around: A trombonist plays while balancing on a tipping ladder held up by a buddy wearing a banjo, which a third friend is strumming.

Bauhaus student Edmund Collein took the shot "Bauatelier Gropius" (aka Gropius' Bauhaus Atelier, 1927-28), which depicts his classmates crammed individually or in pairs into stacked wooden cubbies, peering around at one another or brandishing spoons and teacups. Sassin, who joined Briggs to give this reviewer a tour, declared the photo one of her favorite items in the exhibit.

"I love the zany clothes," Sassin said. "They look so contemporary; they look like art students today."

The Bauhaus students ended up giving Gropius the photo as a parting gift. Still, Sassin pointed out, "[They] often made fun of the stodgy masters."

The exhibit amply demonstrates how imaginative those masters were. Marcel Breuer, a Bauhaus student who became master of the cabinet-making workshop in Dessau, pioneered furniture made from the new seamless tubular steel being used in bicycles. On loan from the Gropius House in Lincoln, Mass., are Breuer's model B5 chair (1926-27), with its distinctive seat material stretched around the tubing and held with crossties underneath; and a set of his model B9 nesting tables (1925-26).

Beside them sit a chrome floor lamp by Marianne Brandt, head of the metal workshop from 1928 to 1929, and Peter Keler's iconic Bauhausian cradle from 1922. The latter is formed from a basic circle and triangle, which were then assigned colors according to the theory of Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky, master of the wall painting workshop through 1925. On a separate wall, Kandinsky's 12 "Kleine Welten" ("Small World") woodcuts and drypoints encourage viewers to puzzle out those theories, which associate particular shapes and colors. Some of the works are colored, others black and white.

- Courtesy Of The Sabarsky Foundation

- "Kleine Welten V" by Wassily Kandinsky

Similarly inspired by Kandinsky's color-form theory, the exhibition design team devised a graphic for the show: an intersecting blue circle, red square and yellow triangle. "Because it is the Bauhaus, we're going a little crazy," Pohlman explained.

A few of the pieces are surprises. Theater and sculpture master Oskar Schlemmer practically saw the human body as an arrangement of geometric shapes — witness his "Triadic Ballet" on YouTube. The poster advertising it appears here. The exhibit also features a 1934 woodcut portrait of Schlemmer by one of his friends, German expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. The work's distorted lines look out of place in an exhibit celebrating the Bauhaus aesthetic.

For different reasons, artist Paul Klee's pedagogical sketchbook from 1925, detailing his theory of form based on the relationship of point, line and plane, surprised this reviewer. Known for an idiosyncratic style inspired by the spiritual, children's art and the mentally ill, Klee appears to have been instrumental in shaping the Bauhaus' elementary theory of "surface" (i.e., two-dimensional) forms. "Students and masters alike regarded Klee's instruction ... as foundational for applied work," the wall text notes.

Sassin and her Middlebury students refer briefly in their texts to the enormous impact of the Bauhaus on art, architecture and industry worldwide. "Weimar, Dessau, Berlin: The Bauhaus as School and Laboratory" is itself a measure of that impact; clearly, the pedagogical side of the pioneering school still inspires students today.

As Briggs explained, the framers of the German school "wanted students to generate original thought. [This exhibit] is really what the Bauhaus was all about."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.