- James Buck

- Polly Motley

It was a performance of contrasts. Head held high, hand on the railing, Stowe artist and educator Polly Motley surveyed the marble staircase, reached for a tread with her foot and hovered elegantly before taking a sure-footed step. Seconds later, she faltered, missed the next tread and crumpled in a heap against the balusters. She exuded refined poise one minute, fearful weakness the next.

Motley's October 3 dance performance at the University of Vermont's Fleming Museum of Art embodied the contradictory experiences of women — from more than a century ago. She and three UVM students were performing works inspired by "The Impossible Ideal: Victorian Fashion and Femininity," one of the museum's new exhibitions.

- Courtesy Of The Fleming Museum Of Art

- Iridescent blue silk dress with mother-of-pearl buttons from 1878

Voluminous silk dresses, boned corsets and high-heeled shoes, as well as photographs and advertisements from popular magazines of the era, show how fashion both reflected and influenced women's behavior and beliefs. The exhibition, which draws primarily from the museum's collection, also chronicles shifting popular attitudes.

"There was a lot of ambivalence during the period," said museum curator Andrea Rosen.

The Victorian era, named for the reign of the United Kingdom's Queen Victoria from 1837 to 1901, is known for fashion that exaggerated women's physical form and restricted their mobility. White women of the urban leisure class, in particular, wore extravagant gowns and were expected to wield power only in the home — and only in support of their husbands.

Yet debates raged in mainstream periodicals regarding whether women should have the right to gain an education, to work outside the home or to divorce. These debates extended to fashion and health, said Rosen, including disagreement on the use of corsets, a few of which are on exhibit at the Fleming.

- Courtesy Of The Fleming Museum Of Art

- Leather and wool gabardine boots, circa 1910

"The bra wasn't really invented or didn't become popular until early in the 20th century," she said, "so nearly every woman wore a corset. That was their foundational undergarment."

Some used it to draw in their waists by about three inches, Rosen detailed. "The tight lacing that we think of — drawing it in by six to 12 inches — was a small minority but a very visible one. That practice was debated in the press."

Women's magazines published numerous letters to the editor from fashion-conscious readers extolling the elegance of small waists, and male and female doctors countered with letters that warned of health risks, Rosen noted. Not until the late 1800s did new fashions popularize more natural waist sizes.

One garment in the Fleming exhibition epitomizes women's shifting roles and identities. Worn by Ellen Miller Johnson for her graduation from UVM in 1878, the iridescent blue silk dress has a moderately cinched waist, no hoop skirt and a manageably short train. "It represents this cusp when more institutions of higher learning are becoming accessible to women," explained Rosen. Johnson became "a teacher at Brigham Academy, a new modern high school of the time. But when she married, she ceased working. That was very common in the era."

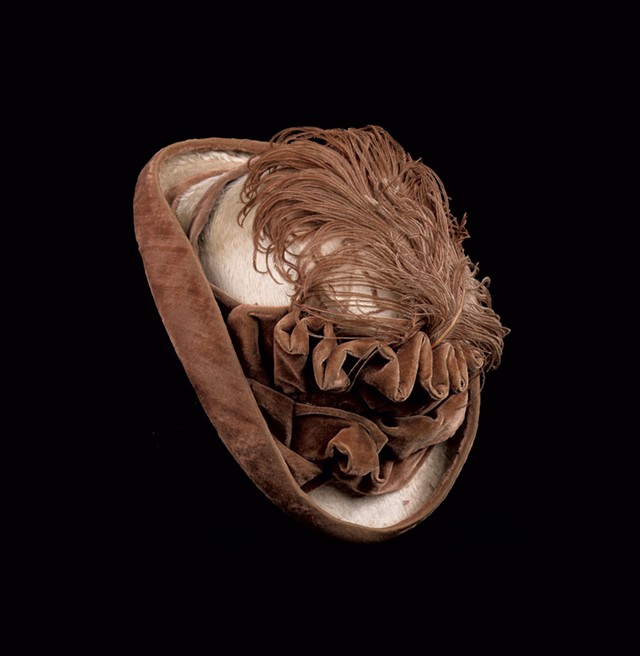

- Courtesy Of The Fleming Museum Of Art

- Velvet hat with ostrich feathers, circa 1900 to 1910

Other items represent more conservative lifestyles: a purple silk carriage parasol with a folding handle of wood and ivory, a velvet hat with ostrich feathers, a Chinese silk fan. These were the accoutrements of women who were unlikely to step outside limited, prescribed spheres.

But leave it to artists to forge ahead. Among the most famous women to challenge prevailing fashion was Isadora Duncan, born in California in the late 1870s and considered the founder of modern dance. She traveled the world performing barefoot in loose tunics patterned after images depicted in ancient Greek art. At the time, her attire was considered scandalous.

"Isadora Duncan grew up in the Victorian era," said Rosen, "so think about all she had to overcome to be bold enough to say, 'I'm good to go around in this sack with no corset on.'"

In last week's performance, UVM student Anna Gibson wore a Duncan-inspired dress as she twirled with delight, lifting her arms and gazing to the sky as if relishing hard-won freedom. UVM student Chloe Schafer danced in a heavy, floor-length dress with fitted bodice and petticoats to an African American folk song. She stumbled under the burdens of life, grabbed her dress fabric and shook it in frustration. A third student, Ariella Mandel, sang the American folk song "Home Sweet Home" and read poetry by Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman.

- Courtesy Of The Fleming Museum Of Art

- Carriage parasol of silk, beads, wood and ivory

"I researched real women [of the Victorian era], and what we were doing is based on some of these characters," said Motley of the performance. Schafer portrayed a southern woman who is "not necessarily a happy plantation owner's wife or daughter," added Motley. "She could be a fourth-generation person from West Africa whose ancestors have intermarried, so she looks very white, but her heart is with the poor people."

Both Motley and Rosen emphasized the importance of acknowledging the experiences of U.S. women at all socioeconomic levels during the Victorian era.

"Despite the fact that our collection is largely what was worn by the upper-middle-class white women, the Victorian woman encompassed a much more diverse representation of identities," said Rosen.

Asked what she hoped viewers would take from the dance performance and the exhibition, Motley replied, "Maybe they'll think a little bit beyond the Victorian era as being an era only of aristocratic, refined women. It was a lot more than that."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.