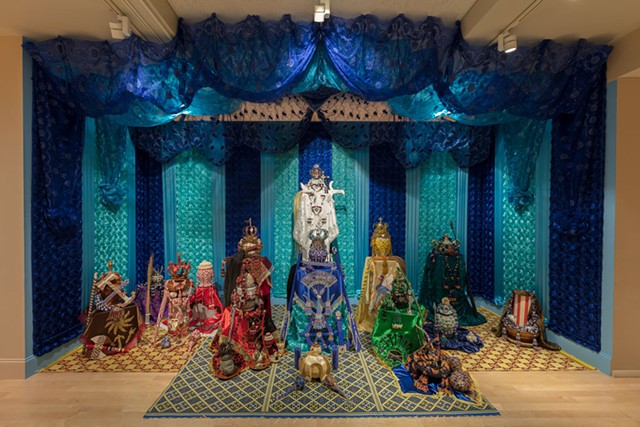

- Gallery view of Cuban Santería birthday altar by William Zapata.

Just past the entrance of the Fleming Museum exhibition "Spirited Things: Sacred Arts of the Black Atlantic" stands a vitrine containing a leather whip, a choker with a heart-shaped rhinestone padlock, and a plastic "male chastity device," all made in the early 2000s. For a show of religious art and objects created by Africans, African slaves and their descendants, this reference to the sexualized Western notion of the "fetish" might seem cheeky at best, strange and inappropriate at worst.

As one delves into the gallery and its abundance of contextualizing labels, however, it becomes clear that complex and exciting arguments about the fetish, race, slavery and reclamation are at the heart of the exhibition. The chief force behind those arguments is J. Lorand Matory, a scholar of West African and African diasporic religions and a professor of cultural anthropology at Duke University. His book The "Fetish" Revisited: Marx, Freud, and the Gods Black People Make is forthcoming in 2018. The professor offered a talk of the same name at the University of Vermont last week.

On display at the Fleming is a vast range of spiritual objects drawn from Duke University's Sacred Arts of the Black Atlantic collection. Among them are vessels such as a pink Cuban Santería soup tureen, sequined Haitian vodoun bottles and flags, and a full Nigerian outfit for possession by the god àngó. Though these are parts of syncretic spiritual practices that evolved geographically as distinct entities, every work shares an ancestor in Yorùbá.

- Cuban Santería/Ochá House of the God Elegguá from the South Bronx.

This religion of West African origin is devoted to a pantheon of spirits known in English as orishas. The Fleming offers several laminated charts featuring the various names of these deities in Yorubaland, Cuba, Brazil and Haiti.

While many objects are clustered by themes, such as "slave spirits" and "gender in the Black Atlantic," four site-specific altars anchor the exhibition. At the gallery entrance stands a "bóveda" altar in the style of Cuban and Puerto Rican practitioners of Spiritism. Matory himself constructed this altar, which includes framed photographs of his and his wife's ancestors, small personal objects such as a toy car and a souvenir bell, a Bible and fresh flowers.

A Haitian vodoun altar and a Yorùbá altar have been installed farther back in the gallery. The former includes five brilliantly colored sequin flags, or drapo, depicting vodoun deities known as Iwas, or Loas. Exhibition text explains that some of these deities are also saints in Roman Catholicism, a faith simultaneously followed by many vodoun practitioners.

The Haitian altar also displays several sculptural objects called pakèt kongo. These are considered to be living gods, made specifically for Matory by Haitian Chief Priestess Marie Maude Evans from cloth bundles of various ingredients wrapped in exuberant fabric, ribbons and feathers. (Evans will conduct a Haitian vodoun ceremony at the museum on October 12.)

- "Pakèt Kongo for Ogou"by Marie Maude Evans.

Occupying an entire gallery niche, from floor to ceiling, is a Cuban Santería birthday altar, or "throne," made by William Zapata. Vibrant blue fabric provides the backdrop for a family of elaborate beaded vessels, each constructed for a particular orisha with corresponding colors and objects. For example, fragments of coral adorn the vessel of the god/goddess of deep waters, Olocun.

This is not, of course, the first time African and African-descended religious objects have appeared in a museum. What distinguishes this show from others, Matory contended at his recent talk, is that historically most or all of these objects were "killed" first. The European practice of stealing and exhibiting African religious art, he said, is one of collecting the "wooden carcasses of African gods."

When Europeans began trading in African slaves in the late 1400s, Matory writes, they described Africans as worshippers of "fetishes," or objects to which supernatural powers are ascribed. The term implied a sense of backwardness; Europeans saw Africans' veneration of their religious objects as evidence that they were misguided, barbaric and less than human.

Later, both Sigmund Freud and Karl Marx adopted the term "fetish" to indicate an incorrect assignment of value — sexual fetishes for Freud and "commodity fetishism" for Marx. Their racist assumption, Matory said in his lecture, was that to fall prey to such thinking was to be "just as foolish as an African" who doesn't understand why or how "fetishes" actually hold power. But, he said, worshippers of such objects and the gods they represent "are highly articulate about how gods are made — they literally say that they are making a god."

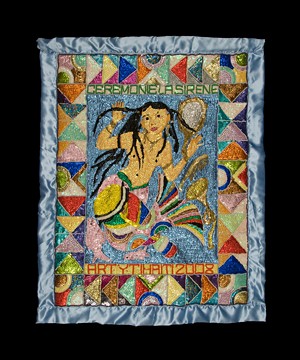

- Flag (Drapo) for Lasirènby Yves Telemak.

Seen in this light, the spiritual artworks on view testify to the agency and resilience of black populations oppressed for centuries by white Europeans. Indeed, the sheer quantity of types of objects speaks to practitioners' talent for embodying their gods and keeping them alive in a multitude of ways. Exhibition text indicates that many of the materials, such as cowry shells and rum, were initially exchanged for slaves, making their use a form of reclamation.

That brings us back to the BDSM gear at the show's entrance, where exhibition text points out that the enactment of sexual fetishes frequently takes the form of a master-slave relationship. Matory pointed out that "white middle-class populations dress themselves in black skins" to enact such power play, referring to the popularity of black leather in BDSM practices. With this in mind, the "tender and terrible" religious objects on view tell a story not only of spiritual survival through slavery but of a centuries-long history of the interplay of objects and racialized power relations.

In contrast with traditional exhibits of such objects, Matory considers the altars in "Spirited Things" to be living embodiments of spirit. As he told his audience at UVM, "The gods you will meet in the gallery have been fed — in Burlington — and they're alive." In this sense, the professor is engaged in reanimating and reconsidering spiritual traditions for a general audience. Mats and instructions are provided for visitors who wish to honor the orishas.

As Matory said at his lecture, "If you want to see the orishas, you will have to prostrate yourself."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.