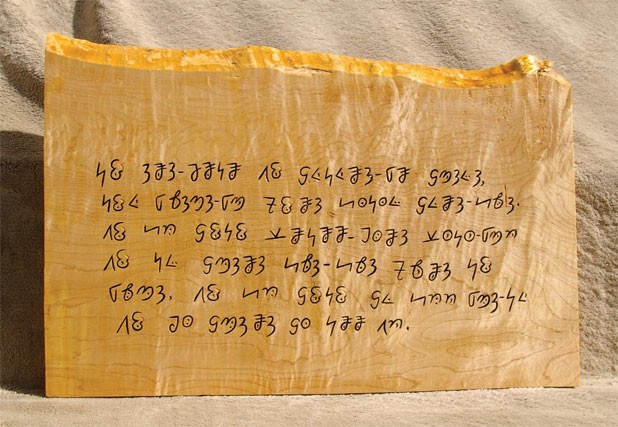

- "Bassa Vah" by Tim Brookes

The dynamics of globalization are always complex and often contradictory. Last weekend, a fascinating and poignant exhibit at Winooski’s Champlain Mill managed to elegantly evoke a seldom-considered aspect of cultural shifts on the planet.

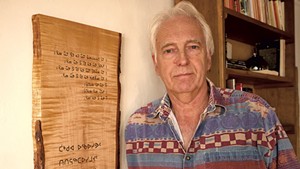

“Endangered Alphabets” brings together samples of 14 writing systems that originated in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and the Americas. Each has been carved onto a slab of Vermont curly maple by Tim Brookes, a travel writer and Champlain College professor. All but one of the alphabets has already fallen out of everyday use or is on the fast track to oblivion.

Bugis, for example, can now be read and written by only a few transvestite priests on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, Brookes explained as his carvings were being hung last week. To the brand-besotted American eye, Bugis’ characters may resemble Nike swooshes accompanied by diagonal sets of dots. Like many alphabets, Brookes notes, Bugis derives its appearance from the material originally used to produce it. Because it was cut into palm leaves, Bugis includes neither circles nor long, straight lines, both of which would have ripped the writing surface.

Anyone who’s ever sent a coded message for a lover’s eyes only may take the demise of Tifinagh personally. This Berber-language alphabet, used by a dwindling number of North African nomads, looks like a combination of Greek and imaginary mathematical symbols. The language it was created to convey is still spoken by more than a million people, but the alphabet itself is being supplanted by Latin or Arabic script. Tifinagh remains useful, however, as a way “to keep the Berbers’ secrets,” notes a wall text alongside the sample of this alphabet. Lovers write letters in Tifinagh, Brookes’ text informs. Directions for finding water may also be inscribed in Tifinagh on desert rocks.

Other alphabets represented in the show include Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Balinese, Bassa Vah, Baybayin, Cherokee, Inuktitut, Khmer, Manchu, Mandaic, Pauauh Hmong and Samaritan.

There’s also Maay Maay — the exception here because it isn’t endangered. This Somali Bantu alphabet uses the same Latin characters as does English and every other European language. Brookes included an example of written Maay Maay as a shout-out to the various groups of refugees who have settled in Winooski. He also intends to suggest that Maay Maay, and other languages spoken by recent immigrants, may be “locally endangered.” Somali Bantu kids growing up in the Burlington area “will soon be speaking ‘American’ only,” Brookes predicts.

Indeed, hundreds of languages are fading into extinction worldwide. Half of today’s 6000 human languages have fewer than 10,000 speakers, the United Nations estimates. And most of those will have vanished by the end of this century.

The global dominance of English, Chinese and Spanish — abetted by their prevalence across the Internet — is hastening the doom of these languages. Naso, for example, will most likely not survive long after its 2000 current speakers die off, since young members of this indigenous group in Panama regard Spanish as a far more practical tongue.

The diversity of alphabets, which number only about 100, is even more imperiled. Within a decade or so, up to one third may no longer be in use, Brookes says.

At the same time — and here’s where globalization gets tricky — new alphabets are being created, while at least one on Brookes’ endangered list (Cherokee) is enjoying a renaissance. His blog on his project’s website notes that a professor in India has created scripts for seven hill-tribe languages that until now existed only in oral form. Brookes learned about this initiative during one of his regular scrolls through omniglot.com, a bounteous guide to the world’s languages and writing systems.

Omniglot illustrates many alphabets by displaying their respective translations of Article One of the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.” Brookes uses the same passage on his pieces. It took him months to find someone — via the Internet — who could write the declaration’s opening section in a particularly obscure script, such as Bugis.

A series of serendipities starting about 18 months ago led Brookes to undertake an endeavor no one else in the world has thought to attempt. “I’d never describe myself as a wood carver,” he says, but he did develop the practice of giving family members Christmas gifts of maple boards that he had inscribed initially with practical wordings and later with Chinese ideograms. That morphed into creating reproductions of endangered alphabets after Brookes became smitten with the appearance of Malayalam, a language he encountered while researching a book in India. A search for information about Malayalam brought him to omniglot’s compendium.

“Endangered Alphabets” is certain to attract attention far beyond Winooski. Brookes is self-publishing a book about the project in June, and the show has been booked into three venues in Britain, with inquiries from other countries now zipping into Brookes’ email in-box. It remains at Champlain College’s Emergent Media Center in the Champlain Mill until mid-June.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.