- U.S. War Department

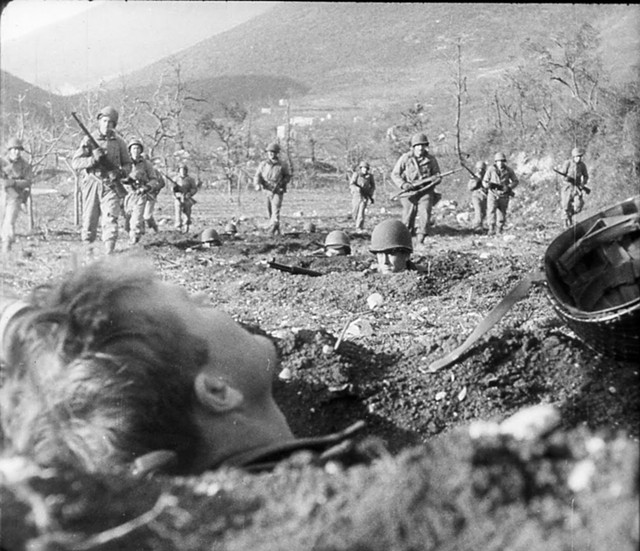

- Death and chaos in The Battle of San Pietro

Regardless of the answers to such trivia questions as this one, filmmakers employed by both the Axis and the Allies shot and developed an incredible amount of footage of the Second World War. Many Western viewers have a general familiarity with such Allies-produced propaganda films as Frank Capra’s Why We Fight series, and many have seen the flag-waving trailers that encouraged viewers to buy war bonds. (One of the better-known such shorts — as well as one of the most controversial; watch it after the jump and you’ll see why — features a crooning, patriotic Bugs Bunny.)

Less familiar to most American audiences are the short propaganda films produced by the Axis powers. Even today, English-subtitled versions of Japanese wartime propaganda films are fairly hard to find, and my cursory search turned up next to nothing. I have seen a few of these, in old 16mm prints, and recall that, above all, they were especially vicious, much more so than their American counterparts.

More familiar, and more accessible, are the films in the German Die Deutsche Wochenschau series. It’s fascinating to watch the films in this series and compare their methodologies to those of American propaganda films. It can be pretty eerie to see how similar they are to the wartime newsreels produced by Hollywood studios. (Some of these films are available on YouTube and other such platforms; to access the films in the official Wochenschau archive, one must log in, but can do so as a “guest” after entering minimal information.)

Many of the Axis films, too, may be characterized as single-minded, even obvious, in their politics. I’m more drawn to ambiguous, complex texts, which is why the WWII documentary to which I return most often is John Huston’s The Battle of San Pietro, released to general audiences in 1945. It’s a bleak, harrowing film that is steeped in bitter ironies — and a completely fascinating one. See for yourself: As a production of the United States government, The Battle of San Pietro belongs to the public domain, so the film has been released as part of numerous anthologies. Archive.org’s version, below, is full and complete.

Clark’s awkward intro was tacked onto the film by the War Department once its high sheriffs had seen the film made by Huston and his crew. Though produced by the U.S. government and intended to rally both troops and home front, The Battle of San Pietro is undeniably an antiwar film.

The story concerns the long and difficult Allied effort to capture the tiny but strategically important town of San Pietro from the occupying Nazi army. Huston’s camera lingers on such images as Allied trucks spinning their tires uselessly in foot-deep mud, mortars landing amid U.S. troops as they struggle to stay on their feet and, most chillingly, dead soldiers: half buried in muck, limbs cracked and disjointed by explosives, loaded unceremoniously into stark white body bags. More harrowing still, some of the dead soldiers are recognizable from shots earlier in the film, in which these men are shown joking around with their comrades.

- U.S. War Department

- The ruins of the titular village in The Battle of San Pietro

For much of the movie, Huston details, with extraordinary precision, the hour-to-hour efforts of the U.S. Army to surmount the hills that will allow them to overtake the occupying German forces. The Nazis, ensconced at the top of the hills that overlook the Liri Valley, have the strategic advantage, and the advance of the Allies is plodding and grueling. At one point, the voiceover informs us that the soldiers have been making small progress at great cost: For each yard they advance, they lose one soldier. It’s a staggering, sobering statistic. Though the Allies did eventually win this battle and take the town, it was at a huge cost: a great many dead and wounded, and the near-total destruction of San Pietro itself.

- U.S. War Department

- One of the film's many body bags.

The U.S. military was under no obligation to release the film to general audiences, yet release it they did. Perhaps military brass saw its grim, ironic realism as a potentially useful tool in “telling it like it is”; perhaps the film was far enough along in the production pipeline that the decision not to release it would have represented a wasted military expenditure.

This is a researchable question to which I don’t know the answer, but I’m glad, in any case, that the film was made and released. It brings a much-needed, and still relevant, ironic complexity to its depiction of World War II, which has, for too long, been regarded as morally unambiguous. As usual, especially with events as enormous and multifarious as those of a global war, the truth is stranger and more varied than most “official records” would have it.

Speaking of...

-

A New Film Explores Vermont’s Unsung Modernist Buildings

Mar 20, 2024 -

Burlington City Council Rejects Pro-Palestine Ballot Item

Jan 23, 2024 -

Rep. Balint Reverses Course, Calls for Cease-Fire in Gaza

Nov 16, 2023 -

A Film Critic Pays Final Respects to the Palace 9

Nov 11, 2023 -

Protesters Disrupt Balint Fundraiser to Demand Cease-Fire in Gaza

Nov 9, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.