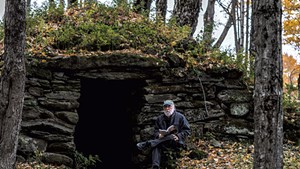

- Ken Picard ©️ Seven Days

- Receiving vault at Prospect Cemetery in Vergennes

Wander around an old Vermont cemetery, or glance at one as you drive by, and you might notice what looks like the entrance to an underground tomb. Dug into a hillside, it often faces north, flanked by stone or brick walls and secured with heavy wooden doors or locked wrought-iron gates.

What are these curious caverns? Subterranean parking garages for cemetery staff? Bargain-basement mausoleums? Cheese caves for ripening Vermont extra-creepy cheddar?

Actually, those crypt-like grottoes are called receiving vaults, and the fact that many Vermonters have never heard of them illustrates how far we've strayed from the age-old custom of tending to our own dead.

Receiving vaults, also known as public vaults, are some of the oldest structures in the state. Indeed, some historians theorize that ancient stone chambers found in eastern Vermont, believed to predate the arrival of European settlers in the 17th century, may have served as prehistoric receiving vaults.

Thomas Giffin is cemetery commissioner for the City of Rutland and president of the Vermont Old Cemetery Association. The nonprofit's name seems a little redundant, given that the vast majority of the 1,900-plus cemeteries in the Green Mountain State are decades or centuries old.

Giffin, a 10th-generation Vermonter who can trace his family's genealogy using old Vermont headstones, has seen his share of receiving vaults. He joked that he nearly ended up in one himself recently, after his appendix burst while he was working on a restoration project in a Weybridge cemetery. Seven Days caught up with Giffin by phone last week, during his convalescence.

Receiving vaults were long used to store the bodies of Vermonters who died during the winter, when the ground was too frozen to dig graves, Giffin explained. Traditionally, every community had one, and they were usually visible from public roads because they had to be easily accessible by horse-drawn carriage during the winter.

Receiving vaults were sometimes used during pandemics, too — to store corpses until gravediggers could catch up on their backlog or until public health officials deemed the bodies safe enough to handle for burial.

Among the most famous occupants of a Vermont receiving vault was Robert Todd Lincoln, who died at his family's Manchester home in 1926. The body of Honest Abe's son was stored for 597 days in the Dellwood Cemetery receiving vault in Manchester Village; in 1928, his widow arranged for his burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

Receiving vaults aren't unique to Vermont; many northern cultures that bury their dead have versions of them. Eastern Vermont is home to 52 ancient stone structures that might have served as receiving vaults. One of the largest, Calendar II in South Woodstock, aligns with the solstice sunrise. According to the New England Historical Society's website:

In 1975, a retired marine biologist from Harvard [University] announced his discovery: On Vermont's stone structures he found inscriptions in a dead Celtic language called Ogam. He concluded [that] Celts from the Iberian peninsula carved them around 1000 B.C. They all faced east and many had inscriptions. And some have symbolic markings, while others have Celtic place names.

A study done two years later by the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation concluded that the stone chambers were not used as burial vaults, kilns or ovens. Whether they were receiving vaults, worship sites or something else remains a mystery.

- Ken Picard ©️ Seven Days

- Interior of receiving vaultat Prospect Cemetery

Today, most of the receiving vaults in old Vermont cemeteries no longer serve their original function. If they're used at all, Giffin noted, they're more likely to house shovels, lawn mowers and weed whackers.

That doesn't mean the need for them has fallen by the wayside.

"They're an absolute necessity here in Vermont," said Randy Garner, president and co-owner of Day Funeral Home in Randolph. "At least half the year, a lot of our cemeteries are closed."

As Garner noted, some local cemeteries close by mid-November regardless of outside temperature. Others, such as the Vermont Veterans Memorial Cemetery in Randolph, take a "wait-and-see approach" to the weather, he said, performing burials as long as they can break ground. Delayed burials put a strain on mourning families, Garner explained, and cemetery staff don't want to push too many interments until spring and then have to play catch-up.

Once the ground freezes, where do bodies go? Some funeral homes have their own receiving vaults in a naturally cold section of their garage or basement, Garner said. He uses a freestanding one that's managed by the Town of Randolph. Unlike older receiving vaults, which may not be waterproof or safe from vandals, the town's concrete building is secure, with steel doors and a large room with racks that hold multiple caskets.

Families can use Randolph's receiving vault for a one-time fee of $50, regardless of the deceased's length of stay. Most funeral homes don't invest in refrigerated units for such long-term storage, Garner said, as the electric bill alone would be cost prohibitive. Plus, Vermont's winters do the job so much better for free.

The state's receiving vaults are likely to see less use in the future — and not just because a warming climate allows burials to happen later in the fall and earlier in the spring. These days, more Vermonters are getting cremated than interred.

According to Vermont Department of Health records, of the 6,027 people who died in the state in 2018, 4,435 were cremated and 775 were buried. Another 313 were listed as being in "temporary storage," which would include those in receiving vaults. The remaining 504 mortal remains were donated, entombed or shipped out of state, with the exception of those mysteriously listed as "other."

With burial numbers dropping like flies these days, cemeteries and funeral directors are the ones getting stiffed.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.