- Luke Awtry

- Andrew Ryan preparing meals at Drifters

Kristin Baker, nurse manager in the emergency department at the University of Vermont Medical Center, opted to skip dinner one recent evening. She wanted to make sure the hands-on emergency crew got plenty to eat from the menu of chicken and rice with sesame and slaw, and rice bowls with hoisin-glazed tofu and vegetables.

"They're the ones running around in all the rooms, and putting on PPE and taking it off all day," Baker said. "The staff raved about it. People were really excited."

The dinner for 75 people, made and delivered by the Great Northern restaurant in Burlington, provided both sustenance and a morale boost for the doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists, technicians and other workers in the emergency department.

The April 9 event was also the inaugural meal courtesy of Frontline Foods Vermont, the local chapter of a national nonprofit that provides restaurant meals to frontline workers in the coronavirus pandemic.

"This was a treat because it was not only great food, it pulled a whole bunch of the staff together in one place at the same time," said Baker, who's worked in the emergency department for 16 years. "It was a moment of decompression. This has been very stressful for people. This [situation] is not normal."

Frontline Foods has a dual mission: to give business to restaurants that are closed during the pandemic (but open for takeout orders) and to feed health care workers, emergency responders and others providing essential services.

Sheramy Tsai spearheaded the founding of Frontline Foods' local branch. Now a school nurse in South Burlington, she formerly worked in the post-anesthesia care unit at the UVM Medical Center. Tsai said she read about the organization in late March and contacted its California founders with an interest in replicating the model in Vermont. The national group works in partnership with World Central Kitchen, a hunger-relief nonprofit founded 10 years ago by chef José Andrés.

In Vermont, Tsai worked with marketing specialist Kyla Paul to build a team of volunteers who would launch the local initiative. The core group of seven women and one man includes medical students who work on marketing and social media, as well as Anna Marie Gewirtz, former executive director of the Flynn, who is managing the fundraising effort.

"If you're from Vermont, you know that our community is just amazing," Tsai said. "Vermont just steps up."

By April 24, two weeks after the Great Northern's delivery to the emergency department, Frontline Foods Vermont had served 918 meals in the Burlington area and raised $88,100, according to Gewirtz. This amount includes pledged donations.

"We've had some amazing responses from Vermonters who are excited about this effort," Gewirtz said, adding that in her fundraising career "this is unlike anything I've ever seen."

The organization had received donations from 266 people around the state by April 24, and the average gift was roughly $200. In addition, a Vermont family foundation contributed $25,000, Gewirtz said. All of the money goes to the restaurants that are preparing and delivering the meals at an average price of $18 per meal, she said.

"I think people in this moment are all asking themselves how they can help," Gewirtz said. "Knowing what our frontline workers are putting themselves through every day — risking their lives to help the rest of us stay safe — is an extraordinary thing, and they absolutely deserve every piece of recognition and thanks we can give them."

Gewirtz praised local restaurants, too.

"We have such a vibrant restaurant community," she said. "And each one of us has a vested interest in keeping our favorite local restaurants alive and thriving."

Last week, Sugarsnap, a catering business in South Burlington with an affiliated farm at the Intervale, made and delivered meals for the staff at Birchwood Terrace. The nursing home in Burlington's New North End was the site of a coronavirus outbreak in early April.

Related Most Burlington Infections Tied to Nursing Homes, New Data Show

Becoming a Frontline Foods participating business was a simple and well-organized process, said Abbey Duke, owner/founder of Sugarsnap. She was talking to a volunteer organizer within days of filling out an online form, and soon Sugarsnap received its first order.

Duke delivered a lunch of roasted chicken thighs with lemon-rosemary sauce, spring vegetable risotto, roasted cauliflower and broccoli, and cookies to the Birchwood staff. Later, Sugarsnap returned with dinner for the night crew: braised brisket au jus, mashed potatoes, asparagus and brownies. The food handoff, made with safety precautions in place — masks and gloves — occurred outside the facility.

"It's one of those circular things," Duke said. "It's spending money in the local economy, which is great, and supporting small businesses and our frontline workers when having something comforting is a wonderful thing."

A resident of the New North End, Duke said she was "thrilled to have some kind of bright light" for people in her neighborhood who are working hard in a tough situation. As a catering company, she noted, Sugarsnap is set up for this kind of job.

"We know the drill," Duke said. "I'll do it as often as they want us to."

- Luke Awtry

- Andrew Ryan and Maddy McKenna delivering meals to Joanne Wallis (right) at the Community Health Centers of Burlington

In the Old North End, Andrew Ryan, chef-owner of Drifters café and bar, was preparing late last week to make lunch for a neighboring organization, the Community Health Centers of Burlington.

The open-faced meatloaf sandwich was offered with Vermont beef or in a vegan version (housemade seitan with white beans and mushrooms), served on house focaccia with roasted carrot gravy, crispy shallots, roasted potato wedges and a side salad.

Born and raised in Burlington, Ryan said he opened his small café on North Winooski Avenue to be part of the community and to feed it. Frontline Foods is an extension of that mission, he said.

"The community we live in supports and helps each other out," Ryan said. "I think Vermonters are more about community and spending locally than other places."

Nationally, Frontline Foods' network of 51 chapters has collectively raised $4.3 million and delivered 215,000 restaurant meals to people working on the front lines of the pandemic, according to the organization's website.

In Vermont, due to "extraordinary response," Frontline Foods raised its fundraising goal last week from $100,000 to $150,000 by May 15, Gewirtz said. "A few days ago [$100,000] seemed like a lofty goal," she added.

Phish is helping to reach that target. Last Friday, the band announced that the April 28 version of its weekly online event "Dinner and a Movie" will benefit Frontline Foods.

"If people feel compelled to give," Tsai said, "we will continue this organization as long as everybody wants to give and we have food."

Meal Train Coming

Shane Switser had no idea Meal Train was based in Vermont when he first used the online platform to organize food deliveries to Northeastern Vermont Regional Hospital. The owner of Pizza Man in Lyndonville was further surprised, and delighted, to learn that Meal Train president Michael Laramee is from Lyndonville and a 1994 graduate of the Lyndon Institute.

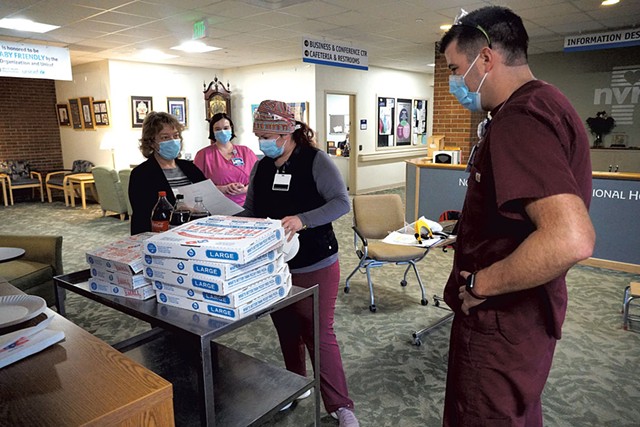

- Courtesy Of Northeastern Vermont Regional Hospital

- Pizza delivered via Meal Train at Northeastern Vermont Regional Hospital

In an email last week, Laramee told Switser that whenever he returns to his hometown to visit his parents, he eats at Pizza Man. It was a neat twist to a Meal Train experience that had already wowed the restaurateur.

"It's a cool community thing that we're doing," Switser said, referring to using Meal Train to arrange food deliveries to the frontline health care workers in St. Johnsbury.

"This was a no-brainer," he continued. "It's a win for the hospital. It's a win for the restaurants because people are calling restaurants and giving them business. And it's a win for the community that wants to give back to the frontline workers."

This use of Meal Train — restaurant deliveries to frontline workers — is a new way to employ the platform. But local communities around the country and world have used Meal Train more than 1.5 million times to organize meals for friends and neighbors since Laramee and Stephen DePasquale founded the company a decade ago. The two are 1998 graduates of the University of Vermont.

Meal Train has facilitated the delivery of some 42 million meals, Laramee said, averaging 10 meals per recipient. Common uses of the platform are organizing meal deliveries for people after childbirth or during an illness, he noted.

"It's innate to want to help people out after they've been through a significant life event," Laramee said. "It's human nature."

The idea for Meal Train grew out of a custom in Burlington's Five Sisters neighborhood, where Laramee lives with his wife and two kids. A group of neighbors would each make a meal for a family after the birth of a baby, he explained.

"That process became difficult to organize each time someone had a baby," Laramee said. "I thought there had to be a better way."

Meal Train was born of his "desire to solve this problem with technology," he said.

When the coronavirus pandemic first emerged, Meal Train experienced a decline in traffic, according to Laramee. He attributes the dip to people's uncertainty about how to use the platform safely before contact-free delivery became a common practice.

"People were nervous," Laramee said, "and they didn't know if this act that they wanted to participate in made sense."

Soon, he added, "insightful Meal Train users" started to use the service to bring together frontline workers, whom communities want to support, and restaurants that need business.

"That has been truly amazing over the past five weeks," Laramee said last week. "We've organized over 1,050 Meal Trains for different frontline employees all over the country."

By April 24, that number had increased to 1,152, with 25 to 30 new Meal Trains created per day for frontline employees, according to Laramee.

In the ongoing Meal Train for the St. Johnsbury hospital, nine restaurants in Lyndonville and St. Johnsbury provide meals on the weekends, when the hospital cafeteria is closed. The business is made possible through $3,000 in donations from community members, Switser explained.

"I called a bunch of my competitors and said, 'Hey, let's do this,'" he said. "It's not about any one place; it's about getting these people fed."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.