- Matthew Thorsen

- Sara McMahon's Movement for Parkinson's Class

Jim Hester knows all about inertia and Newton's first law: A body in motion will stay in motion unless acted on by an external force. Back in the 1960s, the former aerospace engineer worked on the Apollo space missions, developing the engines that lifted the lunar module off the moon's surface.

Today, Hester, 71, applies his understanding of Newtonian physics to a more modest goal: keeping his body in motion while an internal force — Parkinson's disease — tries to slow it down. Five years ago, the Burlington resident was diagnosed with PD, a neurodegenerative disorder that can cause tremors, stiffness, loss of balance and coordination, and other physical and cognitive difficulties.

So far, Hester's PD has progressed gradually. The disease has slowed his reaction times and impaired his balance, making rapid movements more difficult. Sometimes it also takes his mind longer to process information, he says.

- Oliver Parini

- The Binter Center's Push Back PD program

Shortly after his diagnosis, Hester says, he received a valuable piece of advice from someone whose Parkinson's was far more advanced than his. "'Focus on what you can do, not on what you can't do,'" he recalls being told. "The mantra is, 'Use it or lose it.'"

Hester took those words to heart — and is now among a growing number of Vermonters with PD who are finding creative and fun ways to "use it." They're taking up recreational activities such as dancing, juggling, boxing, circuit training and even mime to keep their bodies active and their minds engaged.

Many have discovered these activities through classes developed and funded by the University of Vermont's Binter Center for Parkinson's Disease & Movement Disorders. The center was founded two years ago with a $2 million gift from Nancy Binter, a former UVM Medical Center neurosurgeon, and her husband, Bela Ratkovitz, a former neuroradiologist.* They named it for Nancy's father, Frederick Binter, who died of PD in 1996.

An estimated 1 million Americans, including nearly 2,000 Vermonters, are afflicted with the still-incurable disease, according to the Binter Center. PD is now the second most common neurodegenerative disorder in the United States, behind Alzheimer's disease.

- Oliver Parini

- Gary Martin in the Push Back PD program

Parkinson's will soon pose significant challenges to Vermont's health care system. The U.S. Census Bureau predicts that, by 2030, nearly one-third of the state's residents will be 60 or older, the prime age bracket for developing Parkinson's.

This small state has limited community resources for addressing the therapeutic needs of those with the disease, but that's where the Binter Center comes in. It operates on the principle that keeping older people active and engaged can have major payoffs — not only by reducing long-term health care costs, but also by helping Vermonters live longer and happier lives.

Moving to the Music

It's 10 a.m. on a blustery Wednesday, and Hester is one of 18 students who have just arrived at the Flynn Center Studios in Burlington for a Movement for Parkinson's class. Many enter the dance studio with slow, shuffling strides and careful, deliberate movements. About half rely on walking sticks or canes; a few cling to partners or aides for support. After hanging their coats and removing their shoes, the participants take seats in a circle of chairs.

Leading the class is veteran dance instructor Sara McMahon. For about a decade in the 1970s and '80s, she co-owned a dance studio above Nectar's called Main Street Dance Theatre. Later, she had her own professional dance troupe, Ketch Dance Company, which performed throughout New England.

These days, McMahon, who is also a psychotherapist, works with many people who have little or no prior dance training. She begins by directing her students to sit on the edge of their chairs, backs straight and feet flat on the floor. Her goal is to get halfway through the 90-minute session without a break.

"OK, toes directly aligned with the center of the ankle, the center of the knee and the hip joint. Soft shoulder roll ... elbow circle, arm circle and down, bringing the hands to the belly button," she says. The warm-up exercise is set to slow-paced piano music.

"Remember that starfish image I talked about? We have six limbs radiating from our belly — head and tail, arms and legs. Reach out, and stay out there. Big, big, big!" McMahon instructs. "Now take a deep breath in, let your breath out and let your body deflate, like a balloon. Good! Nice!"

Most of the students appear to be in their sixties or older; a few are younger, including a woman in her twenties. Their mobility and flexibility vary widely. Some are limber, while others are rigid, a signature trait of the disease. One woman in her mid-seventies can barely raise her arms to shoulder level. The twentysomething woman has an aide who moves her arms and legs to the music.

Next, McMahon moves on to the sun salutation and asks her students if they need to review the sequence. One woman remarks, "We have Parkinson's. We don't remember!"

"Yes, you do!" McMahon answers.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Sara McMahon

For 20 minutes, the students perform their reaching, stretching and rolling moves from a seated position. As McMahon explains later, that's about the only modification she makes for people with PD. At its heart, this class teaches students the fundamentals of modern dance.

"When people come in, I don't see them as people with Parkinson's. I see them as dancers," McMahon explains. "I don't say, 'This specific dance sequence works on balance.' All dancers need balance."

McMahon's interest in dance as therapy isn't solely professional. Three years ago, her husband, Gary Martin, was diagnosed with PD. Martin, who'd long been active — he was a taiko drummer and played in a rock band — eventually had to give up his psychotherapy practice because his verbal skills had deteriorated. His coordination has also suffered.

"My big thing is my balance," he says. "I fall backwards."

Fortuitously, around the same time as Martin's diagnosis, the Mark Morris Dance Group, an internationally renowned company based in Brooklyn, came to the Flynn Center for the Performing Arts. Back in 2001, Morris, in conjunction with the Brooklyn Parkinson Group, had developed a program called Dance for PD, which uses dance to help those with the disease improve their coordination, balance, cognition and physical self-confidence. The program is now taught in more than 100 communities in nine countries; it's the basis for McMahon's Movement for Parkinson's class.

On the morning of the Mark Morris show at the Flynn, McMahon attended one of the company's Dance for PD classes. She would go on to attend several more — and then start teaching her own class in Burlington, with support from the Binter Center, the Flynn Center and the Emily List Fund.* Since then, McMahon has expanded the program to Middlebury and Barre. She is considering adding classes in St. Albans and St. Johnsbury.

Forty minutes into the class, the students take a break, during which McMahon clears the chairs. The second half of the class is devoted to improvisation and interpretive dance, done to musical selections ranging from African drumbeats to slow jazz to "The Pink Panther Theme."

In one exercise, the students silently choose a partner from across the room, approach each other and engage in what McMahon calls a "moving conversation" with their bodies. Without exchanging a word, the dancers perform slow-motion swing moves, tugs of war, high fives, bows, hat tips and hugs before separating and returning to their respective places.

"You're creating your own mini moving sculptures," McMahon tells the class. "So let's see you use other body parts besides hands and arms. You have legs, hips, backs..."

One married couple meets and kisses. "Get a room!" someone shouts jokingly.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Sara McMahon's Movement for Parkinson's Class

In another exercise, McMahon instructs her students to approach the center of the studio and, one by one, to build an interconnecting sculpture with their bodies in poses of their own choosing. She doesn't leave them frozen in place for long — Parkinson's does that enough.

Soon the dancers release and separate. McMahon ends the class with a clapping and improv exercise set to Kool & the Gang's "Celebration."

Afterward, about half of the students linger to chat. For many, it's their only outing of the day. McMahon points out that the class' social component is a major reason why attendance is so high. It's an opportunity for people with Parkinson's to commiserate with others facing similar challenges.

Bea Jordan, 74, attends the class with her husband. She's part of a Parkinson's "cluster" in her family that includes her father, a brother, several uncles and an aunt. When asked if she feels different after the class, she answers without hesitation.

"I can move. I can really move," she says with a smile. "Sitting down all day long is not good. I ache. If I move, I don't ache."

Susan Leister was diagnosed with Parkinson's 15 years ago, when she was just 36. Working as a neurosurgical nurse at Fletcher Allen Health Care (now UVM Medical Center), she diagnosed herself with PD before her doctor did. Ultimately, the disease ended her nursing career.

But the headstrong Leister is not taking her PD lying down. She maintains a high level of physical activity — since her diagnosis, she's trekked to Peru's Machu Picchu and gone white-water rafting and zip-lining. She takes McMahon's dance class to help slow the progression of her symptoms.

"Sara really understands the parts of our bodies that aren't working, and she knows how to pinpoint what you need," Leister says.

The benefits of dance for people with Parkinson's aren't just anecdotal. A study published in April in the Journal of Neural Transmission measured the effects of Dance for PD on class participants. The researchers found measurable improvements in the students' physical, mental and emotional well-being, which they attributed to the skills that dance requires: motor planning and memory, visual focus, rhythm, posture and balance control. Those improvements included a 10 percent increase in students' overall mobility, a 27 percent improvement in their walking and gait, and a 19 percent reduction in tremors.

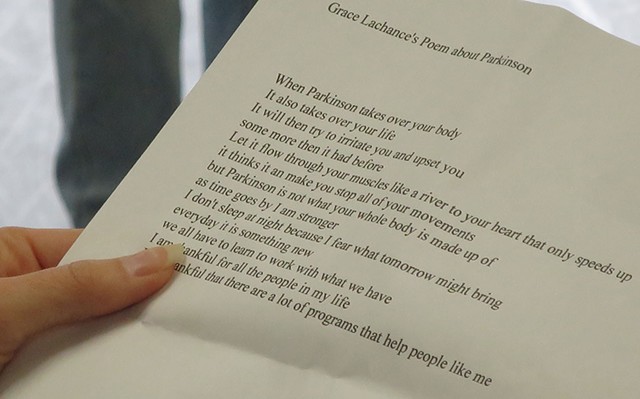

- Matthew Thorsen

- Grace Lachance's Poem about Parkinson

Equally important, the study quoted dance participants as describing their movements, and themselves, in terms not typically used by those with Parkinson's, including "graceful," "focused," "confident," "optimistic" and "fluid." The dancers also characterized themselves as "exhilarated," "much happier" and even "symptom free."

As McMahon's students leave the Flynn Studio, it's evident even to an untrained eye that they're more fluid and confident in their movements. As McMahon explains, the mere act of focusing their attention on how they move their bodies can reduce the "flatness or two-dimensional quality" of the disease.

In short, she says, they're no longer just people with Parkinson's, but dancers.

Mime on His Side

Rob Mermin needs no instruction in bodily self-awareness. The 65-year-old professional mime and founder of Circus Smirkus has spent most of his adult life studying the minutiae of his own movements through space. Now he's applying that training to help people with Parkinson's — including himself — stave off the disease's debilitating effects.

"Pretty much all my adult life has involved movement — doing acrobatics, doing mime, working in the circus," Mermin says during a recent interview in his Montpelier apartment. "So this is very ironic, for me to suddenly be diagnosed with a movement disorder."

Mermin was 19 when he literally ran away with the circus and traveled around Europe as a mime clown. He trained with world-renowned French mime artist Marcel Marceau, as well as with Marceau's own teacher, Étienne Decroux.

Mermin remembers coming home each day from mime class and meticulously analyzing his daily activities. As he washed his face, for example, he'd observe whether he brought his hands to his face or his face to his hands — then memorize those sequences and transpose them to the stage.

The mime first realized something was wrong with his body last year while he was shampooing his hair: His left hand wasn't moving as rhythmically as his right. When Mermin tried to juggle, he discovered his left hand couldn't throw or catch as gracefully, either. When he walked, his right arm swung normally, but his left arm hung limply at his side.

Mermin was finally diagnosed with Parkinson's. His doctor told him he was actually "ahead of the game" compared with most patients, thanks to his circus training.

"When you do mime onstage, you're aware of every gesture you're making," Mermin says. Every movement is planned, like a choreographed dance. But Mermin — who also attends McMahon's Movement for Parkinson's class in Barre — notes that mime differs from dance in that it re-creates everyday physical activities. Furthermore, while dance is meant to look graceful and effortless, mime creates the illusion of an invisible world by making the effort visible.

Today, Mermin no longer performs publicly — "My movements aren't up to my own standards anymore," he says. But he still creates a convincing illusion: An observer wouldn't guess he has a movement disorder. He remains meticulous about keeping those mental notes: where his weight is centered, where his arm rests, how he crosses his legs and which hand he uses to gesture. Mermin notices and compensates for his asymmetric symptoms: If he gestures with his right hand but not with his left on one occasion, he'll purposely use his left hand the next time.

"If I think about it, I do it," he says. "Parkinson's, for me, is like doing mime all day long."

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Professional mime Rob Mermin

And Mermin isn't keeping those skills to himself. Teaching comes naturally to someone who has spent much of his career instructing students in circus skills, both in Circus Smirkus and in college lecture series. In coming months, Mermin plans to offer a class in the Montpelier area to teach people with Parkinson's how to juggle. Rather than using balls, pins or beanbags, he'll start with less intimidating objects: plastic bags from the supermarket produce section. Inflated, the bags float lightly to the ground, which simplifies the juggling process. Mermin has dubbed the activity "baggling."

He notes that the throwing, bending and reaching involved in juggling are precisely the kinds of exercises that physical therapists recommend to PD sufferers to promote better balance, concentration and the use of both sides of their bodies.

Recently, Mermin worked one-on-one with a man with Parkinson's who had difficulties with his balance and frequent falls. For 10 minutes, Mermin's student kept three plastic bags aloft simultaneously. When they finished, Mermin observed that the student hadn't fallen once. As he focused on keeping the bags aloft, he also kept his PD symptoms at bay.

As a young man, Mermin says, he learned a valuable lesson from his mentor: Marceau saw mime as a metaphor for life. When a mime drinks from an invisible glass of water, it's not just a silly pantomime but a drink from the water of life. When a mime stands up from a chair, he's not just one man standing, but all humanity rising to its feet.

These days, Mermin applies Marceau's metaphorical worldview to his Parkinson's.

"You have to keep moving in life," he says, "no matter what."

Pushing Back

Pete Adams stands in front of a mirrored wall with both fists up, like a boxer. Beside him stand six other men and one woman, their arms and fists also in standard pugilist pose. As the music begins — the theme music from Rocky, naturally — UVM physical therapist Parm Padgett calls the shots from the front of the exercise room.

"OK, let's begin with the right hand. We're going to do jab, jab, cross, then come back to center," she says. "Jab, jab, cross! Come back. Jab, jab, cross! Now a little faster."

This is Push Back PD. The weekly circuit-training class, launched three years ago and funded by the Binter Center, was designed for people with Parkinson's. Classes are held twice weekly on UVM's Fanny Allen Campus in Colchester.

Push Back doesn't refer to participants as "patients" or "clients." They're "players." Their physical therapists, and the 10 graduate students from UVM's physical therapy and exercise sciences programs who assist them, are "coaches." Such semantic distinctions underline the philosophy that, while the program is physically demanding, it's also got to be fun to keep people coming back.

Adams is one of three players in this room who also take McMahon's Movement for Parkinson's classes; Leister, the retired nurse; and Martin, the dance instructor's husband, are the other two. For 15 years, Adams worked in the hospital's central sterile reprocessing department. There he prepared medical instruments for surgery — that is, until his Parkinson's made it impossible for him to differentiate their shapes and sizes.

"I just couldn't handle the mental part anymore," he says. "I got too damn slow."

You wouldn't guess that from watching Adams box. He jabs swiftly and with surprising agility for a 74-year-old who's been sparring with Parkinson's for 12 years.

In early November, Adams and several other Push Back players saw a CBS News report by Lesley Stahl about Rock Steady Boxing. The program uses boxing techniques to help people with Parkinson's — including Stahl's husband, Aaron Latham — fight the disease's debilitating effects. Padgett's class asked if she could add boxing techniques to their usual stretching and warm-up exercises, and today's jabbing session is one result. Padgett's colleague, physical therapist Maggie Holt, is now looking to get certified herself as a Rock Steady boxing instructor.

After the warm-up, Padgett divides the class into small groups, assigning two coaches to each. The players rotate through four workout stations: cardio, legs, core and wall. One group lies on the floor and does planks; a second stands against a wall and works on flexibility and posture; a third does leg and balance training; a fourth hits the cardio machines.

In that fourth group, Martin begins alternately walking and running on a treadmill. Like all the players, he wears a blue "gait belt" around his waist, which is tethered to a handrail to assist him if he stumbles or falls. Overseeing Martin is Emily Day, a second-year PT student at UVM.

- Oliver Parini

- Pete Adams

When Martin walks, he occasionally scuffs his feet, Day observes. However, when he runs on the treadmill, his gait and stride are normal. Why? One theory, she explains, is that Martin is tapping into a "motor plan" imprinted in his brain long ago, like muscle memory.

"Your brain takes over and says, 'Oh, I know how to do this!'" she says. "It's really good for us [students] to have an application for the things we've learned in the classroom."

As Martin runs, Day gently reminds him to swing his left arm more. As she points out, Parkinson's is a disorder of the brain, not the muscles, though muscles will atrophy if they're not used. The goal of this class is to prevent that from happening.

Padgett, who's taught this group for three years, says she's seen noticeable improvements in the players' strength, mobility and flexibility. At the beginning, many couldn't plank for more than five seconds. Now they do it for more than a minute. One man, who started the class last spring, initially had trouble keeping up with the others. Then he started walking regularly.

"He came back this semester, and he's like a whole new man," Padgett says.

Why aren't more Vermonters engaged in these forms of PD therapy? One major challenge the program faces, Padgett notes, is finding the resources to offer classes like this one to all the people who need them. Unlike one-on-one physical therapy sessions, Push Back isn't covered by health insurance plans. The Binter Center foots the bill — but, owing to limited space and resources, cannot offer the class to everyone who might benefit from it.

"It's not accessible to most people, unfortunately," Padgett adds. "If we could replicate this class, we could probably do two classes a day, every day."

Moving on to the leg station, Adams balances on one foot for more than a minute. Though he wavers from side to side, it's not for lack of balance. Actually, he's moving to the rhythm of the Greek dance music playing in the background.

"Pete's balance is legendary in this class," notes Rilke Greenmun, another PT student who's helping him.

"Can you tell these guys are sadists?" Adams mutters jokingly. Ironically, he reports later, one of the major symptoms of his Parkinson's has been a loss of balance.

Holt, the PT who coaches the Monday Push Back PD class, says it's crucial that Vermont invest in more programs like this in the coming years, as the state's population continues to age. It doesn't matter whether it's circuit training, boxing, dance or some other exercise, she says. What matters is keeping Vermonters in motion.

"The more we use our physical bodies all through our lives, the better we'll meet the demands of aging," Holt continues. "If you see someone who has Parkinson's, or you think they do, do everything you can to keep them at the gym. To walk away is the worst thing they can do."

*Correction December 2, 2015: An earlier version of this story misidentified one of the UVM Binter Center's founding donors. Her name is Dr. Nancy Binter.

Correction December 3, 2015: An earlier version of this story omitted several supporters of McMahon's movement classes.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.