- Matt Mignanelli

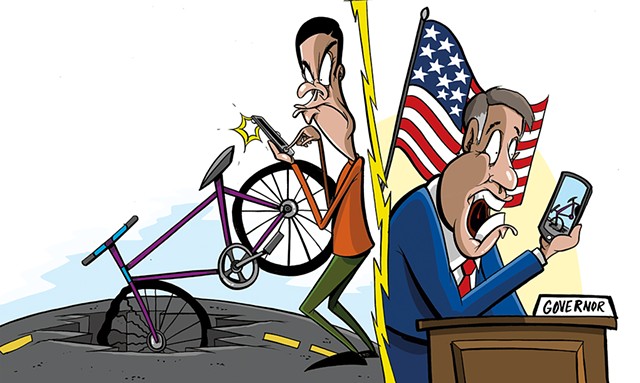

When floodwaters isolated his Norwich neighborhood July 2, Jacques Fordy knew he would be unlikely to reach a state road crew by phone on a holiday weekend. So he tweeted directly at Gov. Phil Scott.

"My neighborhood is cut off from the town, no DOT crews in sight, work on Monday. Send in the boys?" he asked @GovPhilScott at 9:42 a.m.

@GovPhilScott My neighborhood is cut off from the town, no DOT crews in sight, work on monday. Send in the boys? #Vermontstrong

— Jacques Fordy (@BuddhaliciousF) July 2, 2017

At 11:42 a.m., he got a reply from the governor's Twitter account, asking for his location and saying, "Thank you for alerting us."

Less than three hours later, the Agency of Transportation tweeted: "Road should be reopened within an hour or so."

Fordy was pleased with the response. "I chose Twitter because, unlike government, it doesn't have hours," he said. "Twitter was the most effective way to get my message out."

Earl Handy learned the same lesson July 27, when he publicly tagged Mayor Miro Weinberger and the Burlington Department of Public Works.

"@BTVDPW we have about a six inch crater/sink hole forming in front of the diner, due to last weeks work, please come fix @MiroBTV #steamroll," Handy's 7:40 a.m. tweet said. He included a photo.

@BTVDPW we have about a six inch crater/sink hole forming in front of the diner, due to last weeks work, please come fix @MiroBTV #steamroll pic.twitter.com/5YVsMHWAk8

— Earl Handy (@handyslunch) July 27, 2017

At 8:53 a.m., DPW responded: "This patch is on today's work plan."

A minute later, Handy replied, "Working on it now! Thanks."

"Social media's a powerful thing," Handy said afterward.

Government agencies have long used social media to tout their programs and inform the public. Now, more consumers are using those channels to reach out to their government. They are asking what documents they need to register a car and inquiring how much a state park cabin costs per week.

As Handy and Fordy found, using Twitter or Facebook can boost a complaint to the top of the pile.

The trend means government staffers have to up their customer service game. Unlike private emails or phone calls, many social media inquiries are there for all to see. The potential to publicly shame elected leaders is high.

This tactic has been common for several years in the business arena, said Elaine Young, professor of digital and social media marketing at Champlain College. Her advice for government officials: Embrace rather than dread the phenomenon.

"It's the world of customer service," she said. "Meet them where they are."

Young, who has followed social media since its infancy, said smart business owners have turned even the harshest public rants into opportunities to show off their customer service prowess.

If a United Airlines traveler vents to Facebook friends about flight delays, "That's a PR nightmare. You have to show you're responsive and you are on it," Young said. "The ultimate goal is, the person goes back on Facebook and says, 'United solved my problem.'"

"People are becoming increasingly more comfortable connecting on social media," said Alison Kosakowski, who oversees Twitter, Facebook and Instagram accounts at the state Agency of Agriculture, Food & Markets. "I think over time we'll see more."

Kosakowski said the governor has asked state employees to make social media — and customer service in general — a greater priority. Her boss, Agriculture Secretary Anson Tebbetts, a former WCAX-TV news director, "is a big proponent of social media," she said. Last month, for instance, he encouraged the agency to spread the word on social media about goats stolen in Randolph. News outlets jumped on the story.

Kosakowski said a growing number of people are using Twitter and Facebook to contact the agency. "They're in a regulatory pickle, or they saw something that didn't look right," she said.

The Scott administration has not set specific social media rules, according to Rebecca Kelley, the governor's spokeswoman.

"The governor and our office [have] relayed where we think it's a useful tool, such as for constituent service, and emphasized the importance of responsiveness — regardless of channel — but there's not a directive on how to manage channels or whether or not to have them," Kelley said.

Indeed, Young said, social media is not an appropriate avenue for all government interactions, such as those that involve individual social services cases.

But when its use is appropriate, Young said, she doesn't think government agencies will find the work overwhelming. Over time, the tweets will replace phone calls, she said.

Kosakowski said social media catch-ups are part of her workday. "You check a couple times a day," she explained. "A flow kind of develops."

At the Agency of Transportation, where the @511VT Twitter account boasted 8,493 followers as of press time, keeping up with the online conversation is challenging, said Jacqui LeBlanc, the interim public outreach manager.

The agency typically posts information about traffic delays and road closures. The public's questions and comments related to those threads usually go unanswered at night and on weekends, which the agency's Facebook page clearly states.

Providing information via social media is a start, but government could do more to engage with audiences, Young said. That, she said, requires injecting personality into the accounts.

So far, she said, she hasn't seen the governor and other state leaders showing their true colors online. "The person that they are is not coming through," she said. "I'd love to see them do more."

One state social media account that stands out, she said, is the secretary of state's Twitter handle, aka @VermontSOS, which had 1,381 followers. The account offers an edgy mix of humor and information, she said.

She noted the office's lighthearted but apt response August 8 to a Twitter post about Ben & Jerry's cofounder Ben Cohen weighing in on the debate on election fraud. "I scream, you scream, we all scream ... for VOTING RIGHTS," @VermontSOS tweeted.

'I scream, you scream, we all scream for...' VOTING RIGHTS!

— VT Sec. of State (@VermontSOS) August 8, 2017

🗣🍦 https://t.co/fjj2DR7O1D

"They're really kind of upping the game," Young said. "They're putting personality behind government. It allows me to feel even more closely connected. They're actually telling me things."

Some public officials, including Weinberger, tweet regularly themselves. Others usually leave that task to staff members. The governor occasionally authors his own tweets, but usually his communications staff handles the load.

Secretary of State Jim Condos doesn't do the tweeting on his official office account. He doesn't even give himself access, he said, fearing that his responses could be too outspoken.

But maintaining engaged Twitter and Facebook accounts was a conscious decision, Condos said. He sought advice from the National Association of Secretaries of State on that and other communications strategies. Running the accounts is a low-key, in-house operation: Deputy secretary Chris Winters and chief of staff Eric Covey tweet in their spare time.

Winters and Covey haven't shied from making frank, quirky or irreverent responses to commenters.

"We put ourselves out there, knowing we will be subject to scrutiny, but it often generates some good conversations," Winters said.

Take a July 9 exchange, made after President Donald Trump — the tweeter in chief — announced he'd discussed forming a cybersecurity unit with Russian President Vladimir Putin to prevent election hacking.

"Please don't. We don't need that kind of 'help' with our elections," @VermontSOS wrote, dissing Trump. The tweet drew 60 "likes" and 25 retweets.

Please don't. We don't need that kind of "help" with our elections. https://t.co/LuhNWBBIlW

— VT Sec. of State (@VermontSOS) July 9, 2017

Politico later tweeted a report that the president didn't expect the cooperation to occur, prompting @VermontSOS to reply, "Oh good. Probably because we said 'please.'"

Winters said he worries that if he goes too far, his boss will be accused of being partisan, but he has yet to delete a tweet or block a follower.

"I can honestly say: no major regrets so far," Winters said.

Engaging over such hot-button issues can get dicey, but doing so also creates that sought-after personality, Young said. Government, like businesses, must walk a careful line between being edgy and offensive, but they shouldn't be afraid to occasionally provoke, she said.

"It takes some sophistication," she said. "There are going to be points in time when they're going to piss people off."

Anybody who has dipped a toe into Twitter or Facebook knows that social media, which allows users to comment swiftly and anonymously, is a breeding ground for pissed-off people.

Michael Charter, who manages the Twitter and Facebook accounts for the state Department of Motor Vehicles (aka @VTDMV, with 2,112 followers), said he is aware that when he posts links to articles on certain topics — babies left in overheated cars among them — comments will turn harsh.

"We generally let it happen," he said. "If it gets too out of hand, we will delete or block people."

But Charter said he uses the opportunity to correct people who are spreading inaccuracies.

"Somebody the other day wanted to know why people are crossing double yellow lines to pass bikes," he said. It's legal to cross a double yellow line in Vermont when it's safe, and motorists are required to give bicyclists a four-foot clearance, he noted. "When I'm able, I provide links to the legislation," he said.

Eventually, Young said, consumers will likely expect more social media interaction from their government. But will it be the fastest, most accurate way to solve their problems? That depends.

The DMV's Charter said questions posed via Twitter or Facebook likely will get no quicker a response than those made by phone. Kosakowski, at the Agency of Agriculture, agreed. Typically, she receives social media messages and passes them to an appropriate staffer to answer, the same process as when handling a phone inquiry.

But it's hard to argue with the quick response Fordy received about his flooded road or that Handy got after reporting the sinkhole.

Handy said the mayor stopped by the diner after his tweet and told him about the SeeClickFix app, which allows city residents to report and track responses to problems such as potholes, graffiti and traffic light outages. The city has used the program since 2012 and is expanding it to include more public works projects.

Handy said he downloaded the app and will use it next time he spots a problem. But he hasn't forgotten the power of tagging a government official on Twitter when all else fails.

"You know they got it," he said.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.