- Courtesy Of Mary Martialay

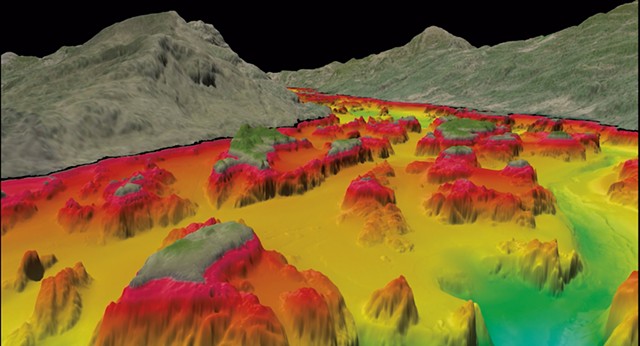

- Bathymetric map

Boaters on Lake George may be forgiven for motoring past the 10-foot-long floating sensor platform, moored in the lake's southern basin, without giving it a moment's thought. At first glance, the unmanned, yellow-and-white buoy bobbing gently in the waves looks like a swim dock or small pontoon boat, albeit a high-tech one that's outfitted with solar panels and a robotic winch.

In fact, this vertical profiler, as it's called, is constantly monitoring its aquatic surroundings from water surface to lake bottom. Sensors measure and record subtle changes in the water's temperature, pH, oxygen content, salinity and dissolved organic matter. The profiler is part of a network of 42 sensor platforms that, by year's end, will be fully deployed in and around the 32-mile-long lake.

Similar platforms on Lake George serve as weather stations, gauging air temperature, wind speed, barometric pressure, humidity and solar irradiance. Some use Doppler technology to track water speed and direction, creating 3D images of water currents, the movements of nutrients and the presence of invasive species. Still others monitor the lake's tributaries for their volume, temperature, turbidity, chlorophyll levels and other organic content.

Together, this web of sensors, linked by IoT (internet of things) technology, generates a river of digital data points — about nine terabytes annually — that flows to remote supercomputers. There, the data are processed, fed into predictive computer models and used in laboratories to create what is arguably the most comprehensive scientific understanding of any major body of water in the world.

All this is the work of the Jefferson Project at Lake George, a unique partnership among Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, IBM Research and the FUND for Lake George. Founded in 2013, the Jefferson Project is turning Lake George into what it calls "the world's smartest lake," with the goal of better understanding, protecting and sustaining this crown jewel of the Adirondack region. The multimillion-dollar collaboration was named for Thomas Jefferson, who visited Lake George in 1791 and described it, in a letter to his daughter, as "without question, the most beautiful water I ever saw."

Rick Relyea, the project's director, is based at RPI's main campus in Troy, N.Y., but he grew up in Clarksville, N.Y., and often visited Lake George as a child. As he explained in a recent interview, Lake George lends itself well to this level of research; neither too large nor too small, it's in the Goldilocks zone of "just the right level of complexity."

The project began in 2013 with a bathymetric survey that mapped the entire lake floor, confirming its topographical richness and diversity, Relyea said. Lake George contains more than 170 islands and is surrounded by mountains and valleys, making accurate weather and hydrological modeling challenging. Its ecosystem is home to a complex food web, ranging from microscopic organisms to large aquatic species.

Lake George is also nearly pristine, Relyea emphasized. Despite considerable development and human impact over the past 40 years and its proximity to major population centers, it's still one of the clearest lakes in the world. The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation has designated Lake George as Class AA Special, its highest water quality rating. This means the lake's water is clean enough to drink — and thousands of residents do just that.

Finally, Lake George has unparalleled economic significance to the North Country.

- Courtesy Of Mary Martialay

- Vertical profiler

"As goes the water quality of Lake George, so goes the regional economy," said Eric Siy, executive director of the FUND for Lake George, a not-for-profit environmental advocacy organization based in Lake George Village.

Environmental conservation in the Adirondacks has generated its share of controversy and rancor, but the Jefferson Project appears to be an exception. Siy noted that the project, which grew from a decades-long relationship between the FUND and RPI's Darrin Fresh Water Institute in Bolton Landing, N.Y., has enjoyed remarkable community support.

"Because Lake George is the economic engine for the region, it's the lifeblood for a $2 billion tourism industry," Siy said. "So all sectors were very concerned about what the science showed."

For years, what that science indicated wasn't encouraging. In 2014, the FUND and the Darrin Institute released a report called "The State of the Lake: Thirty Years of Water Quality Monitoring on Lake George." It identified three primary threats to the lake: invasive species, rising salinity due to road-salt runoff, and declining water quality and clarity. Together, those threats became the focal points of research for the Jefferson Project.

It's not easy to wrap one's head around the project's complexity. Over the past four years, Relyea noted, it has involved more than 250 people, including biologists, limnologists, chemists, engineers, hydrologists, computer scientists and undergraduates from multiple universities. Together, they've generated dozens of reports, journal articles, computer models and conference presentations.

To understand their work, consider just one piece of the puzzle: road salt.

Until recently, Relyea explained, road salt was a topic that had "flown under the radar" for most water quality researchers. But in 2014, the "State of the Lake" report revealed that the salt level in Lake George had tripled since 1980.

"What we didn't know," Relyea said, "was the impact of that level of salt on the plants and animals of the lake." Also unknown was how much salt was flowing into the lake from its tributaries, what could be done to reduce it and whether there were safer alternatives.

Since salt runoff tends to increase during and immediately after storms, researchers wanted to create a network of sensors that could not only measure the salinity of the lake and its tributaries, but also predict, react to and adjust to changing weather and lake conditions.

Harry Kolar is the Jefferson Project's associate director, an IBM Fellow and a physicist focused on environmental science based at IBM Research's headquarters in Yorktown Heights, N.Y. As Kolar explained, because they wanted multi-sensor platforms that were "smarter" and more sophisticated than what was commercially available, scientists and engineers at IBM and RPI designed and built them themselves.

"The sensor platform is very intelligent. It knows what's going on," Kolar said. Constantly communicating with one another, the platforms comprise a highly accurate network of weather stations. If an intense storm is approaching, for example, "We can give you a weather prediction within 333 meters of wherever you want to be in the entire watershed ... every 10 minutes for the next 36 hours," Kolar noted.

Responding to such stimuli, one platform can tell another to increase its salt-sampling regimen from taking measurements once every 15 minutes to once per minute.

The network allows the researchers to test the accuracy of their computer models, to which it is linked using artificial-intelligence technology. Based on what the sensors observe, they can determine the accuracy of models' predictions.

But even these high-tech tools provide only part of the picture. Researchers also wanted to know whether alternative forms of road salt, such as magnesium chloride or calcium chloride, would be safer for the lake's plants and animals.

- Courtesy Of Mary Martialay

- Outdoor tanks functioning as lake simulators

"The answer was, no one knew," Relyea said. That's where the Jefferson Project's laboratories came in. Researchers on RPI's Troy campus set up hundreds of large outdoor tanks to create "mesocosms," or lake simulators, to study and compare the effects of different road salts on aquatic species. (The tanks are also used to study the effects of invasive species and of excess nutrients from septic systems and wastewater treatment plants.)

Eventually, Relyea said, researchers concluded that road-salt alternatives were actually more harmful to the environment than traditional sodium chloride rock salt. These findings are now guiding the policies of townships surrounding Lake George in reducing their application of road salt and finding new ways to control snow and ice.

Kolar noted that the Jefferson Project is working with municipalities to put instrumentation on GPS-tagged salt trucks. The aim is to learn precisely when, where and how much salt they apply to roads — and then measure where it goes.

Those findings are crucial because, as the Jefferson Project discovered, Lake George's tributaries can carry as much as 100 times the salt that naturally occurs in the environment. Such data can be used to strategically reduce road-salt application, saving municipalities money without affecting road conditions.

"It's a clear win-win," Relyea said. "You make it better for the lake ... and you don't do it at the cost of more dangerous roads."

This confluence of state-of-the-art sensor technology, big-data analytics and laboratory research is also being used to tackle other complex threats to Lake George, Relyea noted. These include invasive species — Lake George already has the most rigorous mandatory boat inspection and decontamination program in the state — and excess nutrient loads from septic tanks, aging wastewater treatment plants, lawn fertilizers, and agriculture.

Harmful algal blooms, such as the blue-green algae that has hit Lake Champlain and other lakes in the region, haven't yet affected Lake George. That status allows it to serve as the "control lake" in a $65 million initiative, launched last year by New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, to combat such blooms on 12 regional lakes. It's but one example of how the Jefferson Project is extending its influence beyond its own watershed.

"From day one, the plan has always been to demonstrate that we can do this on Lake George and take everything we've learned and bring it to other lakes around the region and around the world," Siy said. "That's the power of what we're doing. We believe we now have a model for what it takes to protect a threatened water body and watershed."

As for those boaters who now motor past the floating sensor platforms without taking notice, one day they may be able to access the Jefferson Project's vast data stream and know, with pinpoint accuracy, when it's going to rain on the island where they're camping, which fish live in the area and how the water temperature is for swimming.

Now that's one smart lake.

Clarification, July 26, 2017: This story has been updated to fully identify Harry Kolar's title and credentials at IBM, as well as to clarify the description of the multi-sensor platforms used in the Jefferson Project.

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.