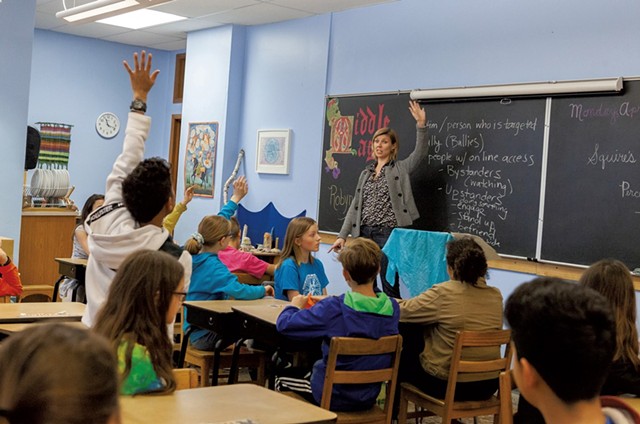

- COURTESY OF CYBER CIVICS

- Lake Champlain Waldorf School students Maggie Goff, Sebastien Mateo Baker-Djele and Juliette Macon (left to right), during a Cyber Civics lesson last school year

In this virtual age, let's sink our hands into what is real.

In this age of light-speed communication, let's learn how to use our inner voices.

In this age of increasingly powerful machines, let's learn to use the incredible powers within.

Once a week, middle schoolers at Lake Champlain Waldorf School in Shelburne recite these words, adapted from an article by education professor Lowell Monke, before their Cyber Civics class. Verses like these, learned by heart through repetition and delivered in unison, are a common way to begin and end classes at the independent preK-12 school, says sixth-grade teacher Rebekah Hopkinson, who began teaching Cyber Civics last school year. The words act to orient students to the work at hand, ground and focus them, and tap into their inner lives.

At first, it may seem incongruous that a class focused on technology begins with such a decidedly heartfelt and low-tech sentiment. However, that would be to miss what's at the core of Cyber Civics. Developed in 2010 by Diana Graber, a California Waldorf charter school parent with a master's degree in media psychology and social change, the three-year middle school curriculum posits that the most important digital literacy skills are, in fact, social and behavioral skills.

During the curriculum's first year, which can be taught entirely without technology, students mull over thorny questions like how their online actions impact the reputations of others, why the attributes of online communication may contribute to inappropriate or bullying behavior, and what to do if they witness or become the target of online hate speech. In the second year, students learn how to find, retrieve, analyze and use online information. And in year three, the focus is on media literacy and how to use critical thinking skills to evaluate media messages.

The curriculum's focus on social and behavioral skills as the foundation for media skills is in line with the Waldorf philosophy, said Hopkinson. Of the 300 schools across the country and abroad currently using Cyber Civics, 130 are Waldorf schools — including one other in Vermont, Upper Valley Waldorf School in Quechee.

Founded by artist and scientist Rudolf Steiner in the early 20th century, Waldorf education aims to help students cultivate their intellectual, emotional, physical and spiritual sides through a strong focus on classical academics and the arts. Students study Greek and Norse myths and medieval history and take part in regular handwork lessons, where they learn skills like knitting, weaving and crocheting. In Waldorf schools, computers and digital technology are virtually absent from the elementary school curriculum. And Waldorf schools suggest that families limit technology use at home as well. Even so, said Hopkinson, the omnipresence of technology is an undeniable reality, and it's important for schools to address it.

She harkened back to the words of Steiner, who said it's the job of the Waldorf teacher to teach the children of today. "And so it's our duty to have the spiritual courage to shift and to change with the times," she said.

She recalled a pair of lessons last school year in which students were asked to examine their "digital diet." For 24 hours, they tracked how they spent time on a weekend day, breaking it down into categories like physical activity, sleep, eating, television, gaming and iPhone use. Subsequently, students went "cold turkey" with technology for 24 hours. In reflecting on the experience, many expressed that it was easy for them to control their own behaviors around technology, but more difficult to avoid screens in their daily lives. "'I couldn't get away from it, even though I really tried,'" she recalled them telling her. "That was really revealing." It also hammered home the point, she added, that, "Unless you remove yourself from society, this is not a choice."

Cory Waletzko, who has been teaching Cyber Civics at the Upper Valley Waldorf School for two years, put it this way: "Digital technology is such an enormous part of our changing world. We would be remiss as a school to not be having students talking about this technology and the impact it can have on our lives."

The curriculum begins with a unit that puts digital technology on the timeline of human history, enabling middle schoolers to see that it's just another human tool that has both benefits and drawbacks, like trains or televisions, for example. When students are introduced to the concept of digital citizenship, discussions center around what it means to be a citizen in any group, whether it's a soccer team or a church or an online community. In these ways, it aligns well with the Waldorf concept of developing an understanding of the big picture before moving to the particulars, said Waletzko.

Last May, Hopkinson led her sixth graders in a Cyber Civics lesson called "A-Okay or No Way," part of a unit that tackled online identity, the risks associated with sharing personal information online and hate speech. According to the curriculum, the lesson was designed to get students to start thinking about the balancing act between sharing aspects of their identity and maintaining their privacy.

Hopkinson launched into the lesson by asking the class, "What is a selfie?"

"It's a funny take on yourself," one student replied.

"Is it something new?" continued Hopkinson.

It's about five to 10 years old, a student guessed, adding that people have been making self-portraits for a long time. The class talked for a minute about a few self-portraits they'd seen previously by Vincent Van Gogh, M.C. Escher and Frida Kahlo, and what the images revealed about the artists.

Then Hopkinson bridged the past to the present with a question: "How can posting personal information online impact your digital reputation?" Students volunteered different scenarios gleaned from previous lessons. If a friend tagged you in a video in which you were toilet-papering a house, that would be bad for your digital reputation. But if a friend tagged you in a photo in which you were doing community service or participating in a rally, that could bolster it.

After watching a short video that underlined the point that online privacy can be affected by others, the class did a short exercise where they had to decide for themselves whether different scenarios were acceptable by moving to signs around the room labeled "A-Okay," "No Way!" and "Maybe."

"Mike" uploading a photo of his dog on his social media account was met with a resounding "A-Okay," while "Laurie" using her mom's login and credit card number to order a dress without permission got a unanimous "No Way!" Other scenarios were murkier, and spurred discussion. Faced with a situation in which "Joe" made online videos, posted them on a site and, when no one liked them, opened a fake account to like and comment on them, the group disagreed. It's dishonest, several students said. But, said one boy, "it's not like you're harming others."

- COURTESY OF CYBER CIVICS

- Soni Albright teaches Cyber Civics at the City of Lakes Waldorf School in Minneapolis

No definitive agreement was reached which, it seemed, was just what the lesson aimed to teach. After all, said Hopkinson, one of her main goals is to help students understand what they encounter online, to be aware of the risks and to weigh them against the rewards.

"The conversations my students have around ethical considerations in digital spaces reveal that most kids want to do the right thing," Hopkinson said. "But the right thing isn't always clear." Cyber Civics allows students to grapple with these issues from an ethical and critical standpoint in class, before they're faced with decisions online, so that they can interact with media in positive ways.

It's not just kids who are grappling with issues around technology use. Hopkinson said that a primary reason the school decided to introduce this curriculum was because parents were regularly asking for support when it came to managing their kids' technology use. "Parents don't know where to start because it's such an overwhelming topic, and I think parents themselves are feeling overwhelmed and addicted," she said.

Last year, while teaching the curriculum, Hopkinson held several informational evenings for parents to explain both the curriculum and the content of Graber's book. "What seems to rise to the surface during these meetings is, 'How can I set limits for my child when I, myself, am still trying to figure out my relationship with my phone?'" she said.

She believes that Cyber Civics gives parents the opportunity to reflect on their own relationship with technology. "I think that, in the teaching of kids — because parents are so invested in their children forming healthy habits — there's the opportunity to examine their own," she said, "so that parents can be more conscious of their own behavior, so they're actually modeling what digital citizenship could look like."

Waletzko of Upper Valley Waldorf School recalled the experience of students going without technology for 24 hours. Some of the adults in their lives also opted to go tech-free for a day. The experience showed her students that "adults around them are striving, just as they are." And families shared with her that "they were able to reconnect with each other" after doing the exercise together.

Amy Brennan is the parent of a 13-year-old daughter in Hopkinson's class, as well as a 9-year-old and 4-year-old who attend Lake Champlain Waldorf School. She said she felt "excited and relieved" when she learned at the beginning of last year that the school would begin using Cyber Civics. She described her generation of parents as "the guinea pigs" and the first to understand "how impactful this technology can be," both in positive and negative ways. Having educators who are helping to give kids a sense of responsibility around technology makes her feel supported as a parent. After a year of the curriculum, she's confident that her daughter has already begun to develop skills that will help her understand the impact of her digital footprint and how she behaves online.

"I trust she will be going into this with understanding," Brennan said, "and know that she can navigate it better now."

As a parent of a 3-year-old son herself, Hopkinson says teaching this curriculum has made her less scared and restrictive about using technology around him. She sees herself as a digital mentor and frequently employs a technique Graber suggests. When using her phone, she narrates her actions aloud so her son can see how technology can be used to do productive things, like find recipes. "And when I am mindlessly checking out, scrolling through my news feed, that is a check for myself, so that's been a very useful tool," she said. With Cyber Civics, she hopes to empower her students, not only to understand what they're presented with when they visit a website, sign up for a social media platform or communicate with someone online, but to create their own social norms around technology.

Right now, she said, we can go to a live theater performance and see people on their phones, or go to the grocery store and see young children staring at screens while riding in shopping carts.

"Maybe those are the norms we want to see, but it's going to be up to this generation to decide that," she said. "I think that if their consciousness is raised to where they feel that they can shape the future of digital technology, that would be a success."

Parent Pointers

- Diana Graber

In her 2019 book Raising Humans in a Digital World: Helping Kids Build a Healthy Relationship with Technology, author and educator Diana Graber — creator of the Cyber Civics curriculum — gives parents practical tips for helping children navigate the increasingly online world. Here are a few of the key takeaways from her book.

- Graber cites researcher Alexandra Samuel, who suggests there are three types of digital parents. The digital limiter is focused on minimizing their children's use of technology; the digital enabler trusts their children to make their own decisions online; the digital mentor plays an active role in guiding their kids onto the internet. Samuel found that the children of digital limiters were twice as likely to access pornography and post rude or hostile online comments than children of digital mentors. If adults don't act as technology mentors, Graber asserts, "kids will be left trying to figure out vast digital spaces without the adult role models or guides they need. Or, even worse, when they do find access to technology, they may binge on the forbidden fruit they were shielded from."

- When using your smartphone or tablet around young children, narrate your actions in real time, Graber says. For example, "I'm not sure what to make for dinner tonight, so let's look for a yummy recipe together," or "The zoo is so much fun! Can I take a picture of you, so we can look at it later to remember what a good time we had together?" Not only does this help kids understand what technology is used for, "it reminds you that you may be using it more than you need to."

- Empathy, Graber asserts, is a critical skill that young people need to navigate their online social lives. But how do parents raise empathetic kids in a world in which digital communication — with its "lack of eye contact, facial expression, human touch and voice intonation" — is ubiquitous? Graber shares insights from educational psychologist Michele Borba, who recommends a host of actions parents can take to foster empathy, including setting up digitally unplugged family time: teaching kids to look into others' eyes; reading books and seeing movies that are emotionally charged; and connecting emotionally with your children during mealtimes, bedtime and car rides.

- Graber suggests creating developmentally appropriate "digital on-ramps" to introduce children to technology slowly and thoughtfully. These focus on the meaningful, productive and creative uses of technology in order to foster positive lifelong tech habits. Some of these on-ramps include:

- For ages 0 to 2, videoconferencing with a loved one while your child sits on your lap.

- For ages 3 to 6, sending texts and photos together to relatives and friends.

- For ages 7 to 9, using creative apps, like a digital sketchbook, together or keeping a digital journal while on a family trip.

- For ages 10 to 12, showing your kids how to download and read e-books and music, or doing school research together.

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.