- Sean Metcalf

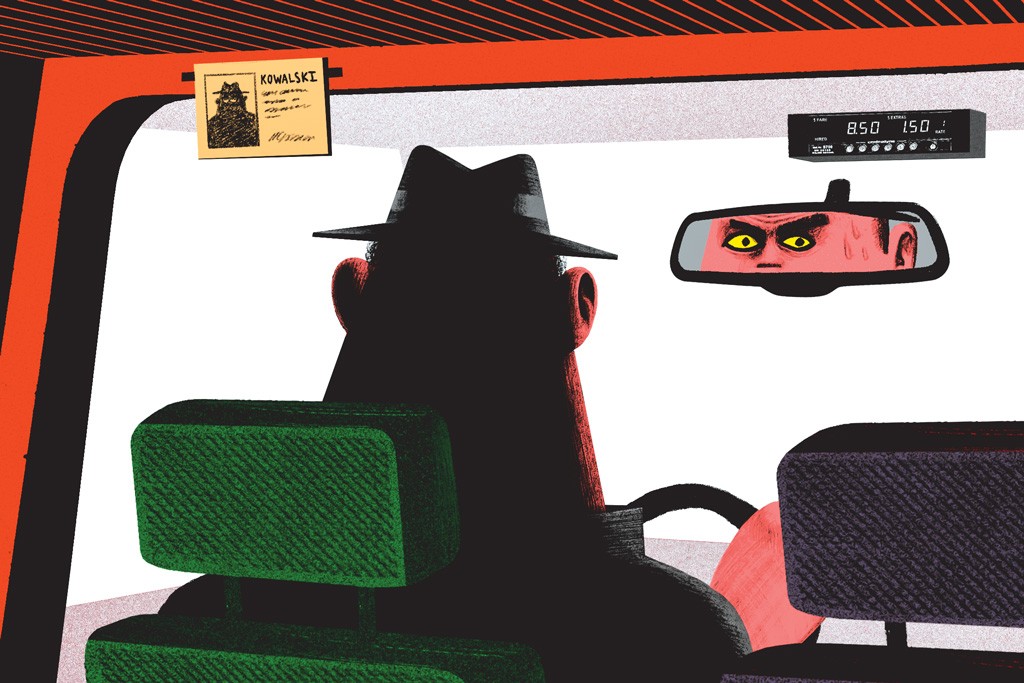

One driver peddled drugs out of his cab. Another posed a lewd question to a 14-year-old girl. A third continued to pick up passengers after getting busted for driving under the influence of drugs. Allegations of misconduct in Burlington's cab industry have so accelerated that one of the regulators recently sent out a plea for help.

In a May 12 email obtained by Seven Days, Isaac Trombley, who runs the Taxi Administration Office at the Burlington International Airport, asked city hall officials: "Does somebody need to get hurt in order for this to become a priority?"

It's no secret that Burlington's taxi industry lacks supervision. But eight months after Mayor Miro Weinberger's administration drafted a report to address it, the problem only appears to have gotten worse.

One company in particular triggered Trombley's email: Blazer Transportation, owned by Ricky Handy, who's been in the taxi business since 1980. Trombley declined to comment for this story, but in an email to other officials last December, he wrote: "This man runs his company the way he sees fit and is constantly challenging our operation, rules and regulation." In his May 12 email he noted, "It has been FIVE months and my office has gotten absolutely nowhere with the violations associated by this company."

The list of Blazer's alleged transgressions include allowing an employee to drive after his license was suspended for a DUI; dispatching an unlicensed driver to pick up people at the airport; doubling up passengers; and charging more than the legal rate. Officials claim that all of these violations took place at the airport, the only spot where taxis and contract vehicles are supervised.

In his email, Trombley added that a Blazer driver told him one coworker was selling buprenorphine out of his company vehicle while another regularly drank on the job.

Asked about the complaints, Handy delivered a lengthy telephonic tirade about the taxi officials, calling them "off-the-wall dictators" who "don't understand what they're doing." He denied charging higher rates but acknowledged grouping separate passengers in the same vehicle, arguing that the city doesn't have the authority to prohibit that. He called the unlicensed allegation a "moot point" because the errant driver has since obtained one.

As for the other complaints, Handy bounced the blame back on those accusing him of disregarding the rules.

While he knew that one of his drivers was going to have his license suspended for a DUI, he insisted he couldn't be expected to know exactly when — "I'm not a walking, talking DMV computer," he said. Taxi officials, he suggested, should have been on top of it. And the allegations about drivers drinking and dealing drugs on the job? "We don't promote drinking and driving, but that's not my business," Handy said. "If they catch some guy drinking, throw the book at him."

Chris Handy, who helps his dad run Blazer, said of the complaints: "The funny thing is, not one of these are about the driver that I fired." He said he recently terminated an employee for repeatedly making inappropriate comments to passengers. The driver told one fare that the glove compartment was "full of condoms." He asked another, a 14-year-old girl, which Red Sox player she'd like to sleep with. Last Handy heard, some other taxi company had hired the man.

According to city ordinance, the taxi licensing board has the power to suspend or revoke licenses for individual drivers and for taxi businesses. Police can also write tickets for violations. So why haven't they cracked down on Blazer?

Jeff Munger, an airport commissioner who chairs the licensing board, explained that nothing can be done without a hearing, and it's proven difficult to schedule one. Handy has canceled twice due to illness and an extended vacation, effectively sidelining the issue for months.

For years, Munger and his colleagues have made the case that they lack the time and resources to enforce the rules and have no way of overseeing drivers who don't come to the airport. In December 2013, he sent a letter to the Burlington City Council that warned: "Anyone can put a magnetic sign on a vehicle as a taxi, operate in the city and never get 'caught.'"

In response, Mayor Weinberger asked City Attorney Eileen Blackwood to draft a report proposing solutions. Almost a year later, she came up with 10 recommendations, one of which encouraged the city to analyze taxi complaint data and, depending on the findings, hire an "enforcement officer."

In the last few weeks, Weinberger finally took action on one of Blackwood's recommendations. He hired a taxi administration officer who will license drivers at Burlington City Hall, removing that responsibility from airport staff. He or she will also be the point person for customer complaints.

His administration has not, however, strengthened enforcement. "The wheels seem to run awfully slow, and that kind of concerns me," Munger said. When she got Trombley's exasperated email, Blackwood referred the issue to the Burlington police.

Blazer may be the latest offender, but it's not the only taxi company that has challenged the regulations.

Last November, the taxi licensing board summoned the owners of Big Brother Security Programs, which primarily transports students with special needs and people with disabilities, to a hearing. The board wanted to know why the company, which started up last summer, wasn't abiding by Burlington's vehicle-for-hire law.

Citing multiple federal and state statutes, co-owner Shelley Palmer argued that Big Brother falls outside city jurisdiction. "If you look at our vehicles, they say 'not for hire' on them," he told the panel.

After the hearing, Munger explained that they would rely on guidance from the city attorney's office to determine whether Palmer was right. "Nobody on this panel knows anything about Title, you know, 20 or Title 49. We're not lawyers."

More than five months later, the company is still "under review," according to Gregg Meyer, the assistant city attorney who advises the licensing board.

In the meantime, one of Big Brother's drivers was charged with driving under the influence. When Christopher Williams, 54, dropped his son off at the Taft School around 9 a.m. on April 7, someone called the Burlington police to report that he was visibly intoxicated. Williams, whose case is still in court, told police he had transported students for the Milton school district earlier that morning.

The taxi drivers would welcome more enforcement — provided it's applied to the ride-share company Uber. They're upset that Uber drivers don't go through the same application process, nor do they follow the same rules — insurance requirements, cleanliness standards, consistent fares — that the city mandates for traditional taxi drivers.

Blackwood has determined that Uber is violating Burlington ordinance, but her office is focused on creating a temporary operating agreement with the company, which it expects to finalize next month. Weinberger said he's going to gather stakeholders in July to discuss possible changes to the taxi ordinance. The mayor added that he's open to beefing up enforcement if stakeholders agree it's necessary, but he's reluctant to "spend money enforcing things that don't need to be enforced."

Uber may be ignoring the law, but when it comes to licensing drivers, its standards may be higher than the city's.

Burlington taxi and contract drivers must apply for special licenses. The Taxi Administration Office runs background checks on all candidates, searching records in the Vermont Crime Information Center, the Vermont Department of Motor Vehicles database and a nationwide database. Licensed drivers must submit to random drug tests and have to reapply for their licenses — including new background checks — every year.

Any one of 13 possible infractions results in an automatic denial, including if a driver owes back taxes, has committed a sexual offense or operated a vehicle while under the influence. The ordinance also gives taxi officials leeway to deny an applicant who they believe poses a risk to the public.

Uber completes annual background checks on its drivers, too. Like the taxi administration office, it searches state motor vehicle databases and a national criminal database. Instead of relying on state databases, the company said it dispatches people to check courthouse records in all counties where the applicant has lived.

According to its website, Uber rejects applicants if they have been convicted of a number of offenses — including DUIs, reckless driving, violent crimes and sexual offenses — within the last seven years. The company also turns down people who have had their licenses suspended in the last three years.

In an interview, Uber general manager Billy Guernier said it also reviews earlier infractions in states that allow it, and Vermont is one of those. Roughly 30 percent of the Burlington-area wannabe drivers have been turned down, Guernier said.

If an Uber applicant fails a background check, they are denied — end of story. But Burlington's screening process is less rigid: Rejected applicants can appeal the decision.

When they do, a quasi-judicial board, which consists of a rotating police officer and two airport commissioners, has sole discretion to make a final judgment. A review of city records dating back three years shows that they nearly always grant licenses to appellants. The panel denied just three appeals between October 2011 and December 2014, according to documents provided by the city attorney. The other 42 appellants prevailed.

Held in a small airport conference room, the hearings are so rarely attended that when a reporter showed up at one, Munger had to ask whether it was open to the public.

Applicants can bring a lawyer, but they rarely do; sometimes a friend, relative or employee comes along as a character witness. The panel listens to their testimony, asks a few questions and then deliberates behind closed doors.

Several Blazer drivers got licenses this way, including Chris Handy and Stephen Hutchins, the latter of whom spent nearly 18 years behind bars for drug trafficking. Part of an infamous smuggling operation, he was arrested in 1991 in connection with $700 million worth of hashish found floating in the St. Lawrence Seaway. Nearly three years out of prison, Hutchins told the panel last July that he was "a different man."

The panel members say their top priority is public safety, but they also believe in second chances. "We hate to deny somebody getting a job or keeping a job," said former city councilor Bill Keogh, the other airport commissioner who sits on the panel.

"Some of the folks were guilty of just being young and misbehaving," Munger noted. "That's why we hold these meetings — to sort of ferret out: Was this just somebody who was young and crazy, or was this a pattern?" Even if someone has multiple convictions, if the crimes are old enough, the board might choose to look the other way.

For instance, in 2011 the panel granted a license to a man with 28 motor-vehicle violations, including three DUIs and a conviction for possession of narcotics. His Vermont driver's license had been suspended 22 times. But, the panel noted, he appeared "honest and forthcoming" and his driving record had been clean for roughly six years.

In 2012 it gave a license to a man convicted of reckless driving and "resisting an officer" in 2007. He had several other minor convictions, and his Vermont license had been suspended 16 times, most recently in 2008. Taxi administration officials also reported at the time that he'd already been driving a contract vehicle without a city license. They deemed him "a hardworking young man who is indeed trying to turn his life around."

What does it take to get rejected for a taxi license? In 2012, the panel denied an applicant who was convicted of domestic assault the year before and had several pending drug charges. At the hearing, he admitted to using cocaine.

This story was corrected on 5/22/15 to accurately reflect the charge mentioned in the first paragraph, driving under the influence of drugs.

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.