- Matthew Thorsen

- Joanna Scott with daughters Bree and Genevieve

The couple, who live in Milton, had some unique scheduling challenges. Jake, a merchant marine — like renowned Vermonter Captain Richard Phillips — worked on tugboats and oil barges along the East Coast and in the Gulf of Mexico. He was on duty for roughly two weeks a month and at home for two weeks.

Joanna worked full time as a family and consumer sciences teacher at Milton Middle School. When he was home, Jake could care for the baby. The rest of the month, Joanna would need to get her daughter ready and drop her off in time to make it to school by 7:20 a.m.

“Trying to find a place to get Genevieve in by seven o’clock was, like, really tough,” remembers Joanna. “The big issue for me was accessibility.” She couldn’t find any openings for an infant locally, which meant she would have to travel to another town to drop off her daughter, then double back to go to work. And though they technically wouldn’t need care during the two weeks when Jake was at home, they would still have to pay for that full-time spot in a childcare center.

Getting help from family members wasn’t an option; all of their relatives lived out of state.

After Genevieve was born, the couple hired one of Joanna’s former students to stay with their daughter in their home — or sometimes at the young woman's place in Georgia, which wasn’t ideal. “We got through the year,” Joanna says of the arrangement, “and Genevieve was safe and cared for.”

For the 2015-16 school year, Joanna asked for a one-year, unpaid leave of absence. She and Jake had sold their house just before Genevieve was born and downsized, moving into an apartment on a rental property they owned in town, closer to Joanna’s school. They calculated that they’d be able to afford Joanna’s leave, given that they wouldn’t be paying for child care.

When Joanna got pregnant with Genevieve’s sister, Bree, during the summer of 2015, she started trying to line up child care for a toddler and an infant. “I could not find a spot for both kids here,” she says. “I would have had to go outside of my town, or drop Bree off at one place, and Genevieve at another.”

One competitive center had two openings, but to secure the spots, the Scotts would have had to start paying for both of them right away. Joanna remembers thinking, “There’s no way I’m paying for six months to hold a spot for a child that’s not even born yet.”

Joanna had to sign her contract for the next school year in March of 2016, around the time Bree was born. She waited until the last minute to make the decision. “I remember being in the birthing center with Bree and discussing ‘Am I going back or not?’ with my family. We had looked for child care, went over our finances,” she says. Jake made more money than she did. It would be easier to live without her salary than without his. “All signs were pointing toward, ‘don’t go back to work.’”

So she didn’t. She turned down her teaching contract to stay home with her kids.

Some parents voluntarily opt out of the workforce when their children are born. But others, like Joanna, are forced out because they can’t find child care. It’s a common but complicated problem that multiple organizations in Vermont are now highlighting and hoping to fix.

Cary Brown, executive director of the Vermont Commission on Women, points out that many in the state are currently sounding the alarm about the shortage of workers. Why not help parents who want to work stay employed? “If we’re worried about our workforce declining,” she says, “we need to take advantage of the workforce we do have.”

‘Such a common thread’

- Matthew Thorsen

- Joanna, Bree, Jake and Genevieve Scott preparing dinner together

According to the group, more than 70 percent of Vermont children under age 6 have all parents in the workforce, meaning that they likely need care. But half of those infants and toddlers don’t have access to regulated child care providers, and nearly 80 percent lack access to high-quality providers — those with four- or five-star ratings in the Step Ahead Recognition System maintained by the Vermont Department for Children and Families.

Let’s Grow Kids campaign director Robyn Freedner-Maguire says it’s impossible to know exactly how many Vermont parents make this difficult choice — the Vermont Department of Labor doesn’t keep those statistics. But when a two-parent, heterosexual couple can’t find child care, chances are, it’s the mom who leaves her job or cuts her hours. According to a national study of individuals with at least honors-level bachelor’s degrees, cited in Sylvia Ann Hewlett’s Off-Ramps and On-Ramps Revisited, women are three times more likely than men to make that choice.

Freedner-Maguire says she’s heard this same concern from women all over the state. A mom herself — she and her partner have three school-age kids — Freedner-Maguire has heard from many women who’ve left jobs, moved to part time, or refused raises for fear of losing child care subsidies.

“It is just such a common thread,” she says. “I have not met very many women, in particular, who don’t have some kind of story.”

Opting out of the workforce has numerous negative consequences for women and their families, Freedner-Maguire adds. Joanna is familiar with them all.

Leaving her job meant that she gave up the seniority she’d built in the Milton school system, and she lost retirement benefits and what she would have paid into Social Security. She let go of access to health insurance (though her family is covered through her husband’s employer). Joanna also lost the salary increases she would have earned as she completed training and staff development.

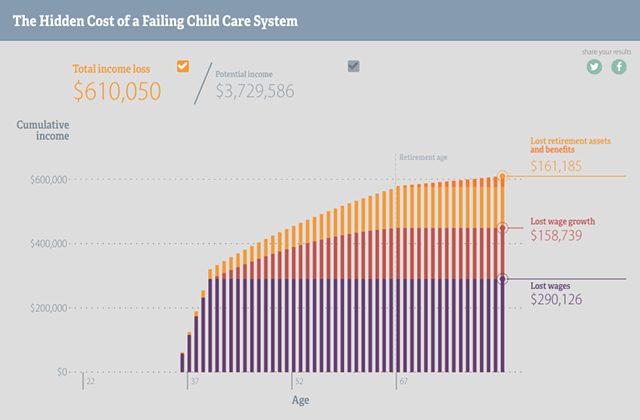

All those losses add up. According to the Center for American Progress’ “Loss in Earnings” calculator, a woman earning Vermont’s median income — $56,990 a year — who gave birth to or adopted a child at age 35 and remained out of the workforce until the child was eligible to enroll in kindergarten, would face a projected loss of $610,050 over her lifetime. That figure includes lost wages, lost wage growth over her career and loss of retirement assets.

That’s an eye-popping number. But it still doesn’t measure the true cost to these parents — or to Vermont.

‘She was a great educator.’

- Courtney Lamdin / Milton Independent

- Former Milton teacher Joanna Scott poses for a photo with students in her Healthy Living class at MR Harvest Farm in South Hero during a field trip in October 2013.

The two eventually moved to Vermont, where Jake had spent summers with his dad, who had since died. At that time, Joanna decided to pursue a teaching career and determined that she wanted to work with middle and high schoolers. After the move, Joanna enrolled in a graduate program at the University of Vermont and later transferred to the Teacher Apprenticeship Program run by Champlain College.

She got her teaching license in the spring of 2009 while working as a substitute in the Milton school district. That led to her full-time gig there as a family and consumer sciences teacher, starting that fall.

A passionate advocate for teaching kids about cooking and nutrition, Joanna made a significant impact on the district in a few short years, as evidenced by stories in the town’s weekly newspaper, the Milton Independent. In 2013, editor Courtney Lambdin chronicled a field trip Joanna took with a few dozen eighth graders to a local farm, where the kids helped harvest vegetables for the cafeteria.

A 2014 story celebrates a team of Milton middle schoolers who won a top prize in the state’s Jr. Iron Chef competition — Joanna coached a team and initially helped launch the initiative in Milton. Another article spotlights a series of community dinners that Joanna helped organize in 2013-14, when she served as the district’s wellness coordinator — a position she created for herself by winning a grant for a yearlong, district-wide wellness initiative.

Even more remarkable: Joanna’s job took her all the way to the White House, where she and some of her students helped plant a vegetable garden.

First Lady Michelle Obama invited them. Milton food service director Steve Marinelli caught the attention of Obama’s Let’s Move! Campaign with a blog post about the district’s self-serve fruit and vegetable bar. Joanna, acting as wellness coordinator at the time, was a partner in Marinelli’s work; when the kids and Marinelli traveled to Washington, Joanna went as a chaperone.

As she recalls, they had just two weeks to fundraise and prepare for the trip. “It was quite the whirlwind,” she says.

When the group returned to D.C. to help harvest the garden, Joanna stayed in Milton to host then-governor Peter Shumlin at Milton Elementary and Middle school; he came to sign a budget bill that boosted funding for school lunches. The Milton Independent dubbed May 28, 2013, a day of “state and national recognition for Milton’s burgeoning school food program.”

Marinelli credits Joanna with starting that program. His former colleague, whom he describes as “a community champion,” was on the committee that hired him. “Joanna really planted the seed of nutrition here,” Marinelli says. “We just kind of carry it on.”

When Joanna assesses the impact of leaving her teaching job, she considers the toll of giving all of that up. “Leaving education was a blow,” she concedes. “I left a program I had worked really hard on developing.”

And she had plans to do more. Inspired by her year as the district’s wellness coordinator, Joanna entertained the idea of becoming a principal or an administrator. She enrolled in a master’s program in educational leadership at UVM and needs just a few more classes to earn her degree. She’s still paying off her student loans.

Joanna often gets teary talking about her decision to leave teaching. “The kids at school taught me so much,” she says. “My colleagues taught me so much.”

Veteran Milton High School consumer sciences teacher Joanne Davidman was sorry to lose Joanna. “She was a great educator in every sense of the word,” says Davidman. When she heard her junior colleague was leaving, “I was so disappointed for the kids,” she says.

After Joanna departed in 2016, the district eliminated the middle school consumer sciences program. Health education was shifted to the physical education department. No one teaches classes in which middle schoolers learn life skills like cooking, sewing and budgeting. Even if Joanna wanted to go back, her job doesn’t exist anymore — she lost the opportunity to work in her community at a job she loved.

Would the district have eliminated that program if Joanna had stayed on? “No,” Marinelli says, “absolutely not.”

It’s an example of the ripple effects that a lack of access to child care can create.

Change The Story VT — an effort to improve economic security for Vermont women — gathers data on the impact of family-care responsibilities, which women disproportionately shoulder. The initiative is a partnership among the Vermont Commission on Women, Vermont Works for Women and the Vermont Women’s Fund. Nevertheless, Jessica Nordhaus, director of strategy and partnerships at Change The Story, points out that lack of access to child care is not just a women’s issue. “It’s an issue for us all,” she says.

‘This crazy tug-of-war’

- Matthew Thorsen

- Jake, Bree and Genevieve Scott piling into the car

Brown, of the Vermont Commission on Women, points out that it’s “very, very common” for women in this situation to sacrifice compensation for flexibility. “This is part of why we have a wage gap” between what men earn and what women earn, she says.

Neither of Joanna’s girls is enrolled in full-time child care, though Genevieve attends preschool at the Saxon Hill School in Jericho on Tuesdays and Thursdays, from 8:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. The Scotts pay for tuition using funds provided by Act 166. On the weeks when Jake is working, Joanna makes the 28-minute trip to drop her off, and returns to pick her up.

Joanna wishes a comparable preschool were closer to home, but she raves about Saxon Hill, a parent cooperative, where she says Genevieve gets “stellar” care.

Joanna still puts in up to 30 hours a week at her job. To find time for work meetings and answering emails, she relies on a patchwork of care that includes local teens who sometimes come over after school to play with the kids. She can also drop off the girls for two hours in the playroom at her fitness club. She might use the time to work out, or to attend meetings at the nearby YWCA office in Essex Junction.

The health club option isn’t ideal, but it helps. “I use it as kind of a Band-Aid,” she admits.

At 7:20 a.m. on a Monday morning in April, when Joanna would have been preparing for the day’s classes, the 38-year-old mom is instead cleaning out her blue Town & Country minivan for the day’s travels. It’s a week when Jake is working, so she’s the sole parent on duty.

- Matthew Thorsen

- Joanna and Genevieve Scott collecting eggs from their backyard hens

She mentions that she woke up at 4:15 a.m., when a smoke alarm started chirping. It had woken up the girls, too, but they’d gone back to sleep, so Joanna had had more time to cook, clean up and answer a few emails.

After dumping ingredients into a crockpot for the night’s dinner — a Tex-Mex concoction with ground beef, tomatoes, onions, corn and beans — she admits that all this multitasking sometimes makes her dizzy. “It’s all this crazy tug-of-war between kids, job, house, self,” she marvels. She sounds determined, not bitter.

To manage it all, Joanna carves out time to plan her days. “I have to schedule to schedule,” she says with a laugh. “That’s my life.”

Once the girls wake up, Joanna cheerfully and patiently helps them get dressed and eat breakfast while she packs clothes and snacks. They’re headed to the health club while she goes to a 10 a.m. meeting about helping children of Vermont’s migrant workers attend summer camp.

Joanna makes herself a large iced coffee to drink on the road. When Genevieve says it looks yucky, Joanna calmly chides her: “Don’t yuck someone else’s yum.”

Joanna had hoped to be on the road by 9:30 a.m., but by the time she gets everything packed up and the kids in the car, she’s running a few minutes late. Once she’s on the road, she pauses to assess herself. “Now I check: Do I have underwear on? Do I have a bra on? OK, brush teeth? Check,” she says with a smile. “I find humor helps.”

Though her life may sound chaotic, Joanna recognizes that she’s more fortunate than many other women in her position. “I’m privileged,” she says. “I have a car. I have a bank account.” She points out that she and Jake were lucky to have a rental property that helped finance her decision to leave teaching.

Though Jake describes Joanna as “basically a single parent” during the weeks when he’s working, she’s quick to correct him. According to Change The Story, the poverty rate for families headed by single women is 37.5 percent — five times the rate of married couples. For those women, accessing affordable, high-quality child care is much, much harder.

‘Get involved.’

- Matthew Thorsen

- Genevieve Scott with mom, Joanna

The Vermont Commission on Women, Change The Story VT and Let’s Grow Kids are all advocating for a number of measures designed to help increase access to affordable, high-quality child care. They want to raise the amount of money families receive through the state’s child care assistance program; make it easier for child care workers to access higher education, which will improve the quality of care; and create a family leave insurance program that will give workers some paid leave.

Change The Story is also reaching out to employers to explain that family-friendly workplace policies — such as being flexible with scheduling and allowing employees to work remotely — can result in fewer sick days, better retention and increased productivity.

Ready to take action?

To sign the Let’s Grow Kids petition, and receive updates about related news and volunteer opportunities...

Most importantly, these groups are focused on identifying and organizing women who are most affected by the child care shortage. Let’s Grow Kids mobilizes volunteers to speak with community organizations such as Rotary groups and with lawmakers. Busy moms who don’t have time to volunteer can sign a Let’s Grow Kids’ petition, available at letsgrowkids.org. It reads:

To sign the Let’s Grow Kids petition, and receive updates about related news and volunteer opportunities...

“I support prioritizing children and increasing public investments in high-quality, affordable child care to ensure every Vermont child has a strong start.”At the beginning of each legislative session, the organization presents lawmakers with signatures from across the state.

Says Freedner-Maguire, “We really need to deepen legislators’ understanding of how challenging it is for Vermont families, and especially for women in the workforce.”

Joanna has recently started volunteering with Let’s Grow Kids. She’s helping to start a Milton/Georgia Action Team — a group of passionate community members who organize locally to strengthen the movement for high-quality, affordable child care.

“I encourage everyone to take initiative, get involved, be it small steps or large leaps in their communities,” she says.

Joanna’s current community involvement also includes organizing a Stand Against Racism event for the YWCA at the Statehouse, volunteering with the Milton Artists Guild, serving on the governing board of the Saxon Hill School, putting together a YWCA Vermont Women’s Weekend at Camp Hochelaga in August and launching a new Navigating Diverse Identities Mentorship Training with the nonprofit Milton Community Youth Coalition.

She’s able to fit all of this in around taking care of her kids. Occasionally that means FaceTime-ing with a committee from the minivan, while one daughter naps and the other watches a video. “Sometimes DVDs and lollipops make it happen,” Joanna says.

She hasn’t ruled out going back to education. Her teaching license expires in June, and she plans to renew it. “I will keep the door open,” Joanna says. “I’m still a teacher.”

Calculating the Cost

The Center for American Progress’ “Loss in Earnings” calculator adds up what parents lose when they are forced to leave work due to the lack of affordable, accessible child care.A 34-year-old woman earning Vermont’s median income stands to lose $610,050 over the course of her lifetime.

- Center for American Progress

- Earns an annual salary of $56,990 a year

- Plans to welcome a new child at the age of 35

- Will remain out of the workforce for five years

- Began working at age 22

- Contributes five percent to an available 401(k) and her employer also contributes five percent

- Will retire at age of 67

- Has a life expectancy of 82 years

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.