Paij Wadley-Bailey was the kind of fearless and charismatic person who could win over an audience. Seven Days creative director Don Eggert remembers gatherings in the late 1990s where the exuberant LGBT and antiracism activist would warm up the crowd. "She loosened people up and invited them to participate," he recalled.

She might break the audience into sections and assign each group a sound to make or words to say. Eggert remembers an LGBT event at the First Unitarian Universalist Society at the top of Church Street where Wadley-Bailey, a lesbian, instructed one group to say "bull dagger," elongating the U in bull. Another group was assigned the term "big old queen."

Wadley-Bailey played conductor, giving the audience their cues. Terms that might have been used as insults were transformed into a kind of music. "Each of the rhythms kind of came together to make a spoken-word song," Eggert explained. "She said, 'Look what happens when all of our voices come together. Isn't it beautiful?'"

Wadley-Bailey died on August 18, 2016. She's one of eight individuals we chose for our annual end-of-year feature on Vermonters who died during the past year. Others include a doctor who helped reform Vermont's health care delivery system, a drummer who gave his final performance a few weeks before his death, a renowned potter who worked in an isolated Northeast Kingdom town and a centenarian who grew up on a dairy farm and met her husband at a square dance.

None of these individuals is famous — like Prince or David Bowie or any of the other celebrities who departed in 2016 — but each Vermonter led a life that was remarkable in its own way. Together, their profiles reveal the wide and wonderful variety of people who, by birth or by choice, have made this state their home. It's quite a chorus.

— Cathy Resmer

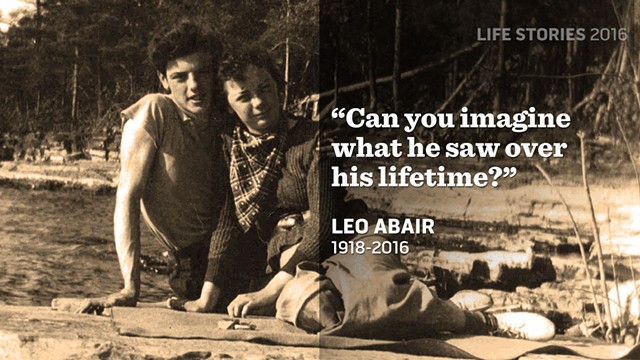

Leo Abair, 1918-2016

As Lake Champlain swelled to historic levels in the spring of 2011, 93-year-old Leo Abair sprang into action. The decorated military man directed family members, friends and neighbors as they built a buffer to save his lakeside home from rapidly rising floodwaters and whipping winds.

"Ever the commander, the Colonel stood at his post in the sunroom and oversaw the operation for three weeks until the water finally subsided," recalled daughter Marilee Abair Cain.

The Colchester property was a dream home, nicknamed "Broadlake," that Leo bought with his late wife, Mary. They'd wanted a place to gather with their nine children — a clan that has grown to include 15 grandchildren and 17 great-grandchildren. Leo, a quintessential patriarch of the "greatest generation," who lived through the Great Depression and World War II, died at Broadlake this summer at the age of 98.

He was the youngest of eight, born in Winooski in more modest circumstances at the family home on Weaver Lane, which was back then a dirt road behind the Winooski Block building. His parents' first vehicle was a horse and buggy.

"My father provided us with food; he raised a garden, chicken and cows," Leo recalled in a 2012 interview with his grandson, Matt Ketcham, for a school project. "That was our food for the year. My mother would can all of the vegetables we didn't use, and that would be our supply for the winter. Milk was such a commodity back then that we didn't drink it ourselves; we sold it to the neighbors."

Leo met Mary Elizabeth Leddy in 1935 and, according to family legend, told a friend, "That's the girl I'm going to marry." They wed in 1942, before he left home to serve in the Army Air Corps.

Leo had gotten his pilot's license as a civilian. The army recruited him to fly small, unarmed single-engine planes — known as "L-birds" — behind enemy lines in the Philippines to help direct artillery fire. His wartime heroics earned him a Silver Star for valor; he also received an Air Medal for meritorious service for his actions under fire during the Battle of Manila.

Like many of his generation, Leo didn't talk much about the war after returning from overseas. But he translated his flying skills into a career with the Vermont Army National Guard, becoming the outfit's first pilot. He stayed on flight status to earn an extra paycheck and, over the years, served as state maintenance officer before rising to chief of staff to the adjutant general. He retired in 1977 with the rank of colonel. Leo later helped found the Vermont State Guard, an all-volunteer organization that assists the National Guard. He retired from that as a major general in 2000.

Bill Keogh, who was a member of Leo's Vermont National Guard staff, remembers his boss as a leader and a good delegator. "He was easy to work with," said Keogh, 86. "He didn't tell you how to do something or how not to do something — he just said do it."

Leo oversaw a burgeoning brood at home. "Everybody knew he was a big-deal military man," said son Alan. "But at home, he was just Dad, running herd on nine kids."

A lifelong piano player, Leo instilled a love of music in his children, several of whom pursued musical careers. Singer and songwriter Phil Abair, the youngest, plays keyboard and bass guitar. He's the leader of his own band and has appeared onstage with members of Phish. He said both he and his father performed aboard the steamboat Ticonderoga: Leo as a teen when the ship cruised Lake Champlain, and Phil decades later for a wedding at the Shelburne Museum, where the boat now resides on land.

Leo and Mary moved to their Colchester home in 1971, then spent winters in Florida after Leo retired. Broadlake became the family's place for summertime fun, holidays, birthdays and all sorts of outdoor events — including, of course, beachside concerts.

"It was the gathering place — every Sunday, pretty much," said Alan. "We'd all end up out there and end up around the piano, usually, before the day was done."

Mary, described by daughter Marilee as Leo's "companion and dearest friend for 75 years," died in 2008. "They were high school sweethearts," said granddaughter Molly Abair. "It was a lifelong love affair."

As a widower, Leo played golf, visited Florida, filled out crossword puzzles, and hosted family and friends. Long an early adopter of new technology, he used Skype, Facebook and games such as Words With Friends to stay in touch with faraway loved ones.

"It was really amazing to see him stay up to speed on all that changing technology," said Molly. "Can you imagine what he saw over his lifetime?"

Before his death, Leo arranged for his family to retain ownership of his lakeside home so they can continue to gather there. His greatest legacy, Leo's kin agree, was the close-knit family he left behind.

"Papa and Grammy are profoundly missed, but the fond memories they left us outnumber the grains of sand on Broadlake beach," Molly said. "The truth is, we are all better people for having them in our lives."

— Sasha Goldstein

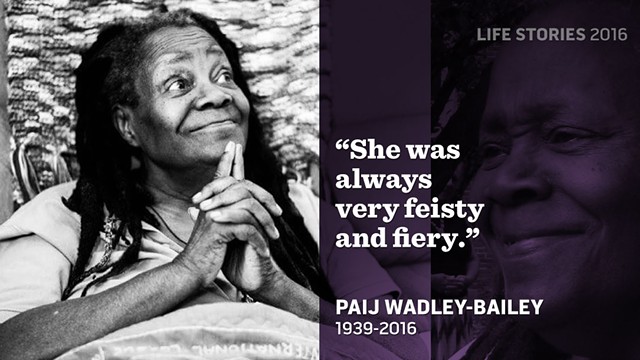

Paij Wadley-Bailey, 1939-2016

The night Barack Obama was elected president, Paij Wadley-Bailey got down on her knees in front of the television set and exclaimed, "We did it! I can't believe we did it. This is history right here!"

She was watching the returns that night at the home of friends in Worcester. One of them, Sara Baker, recalled the occasion in an email.

Paij was a black lesbian who dedicated her life to social and political activism and welcomed a wide range of people into her sphere. The election of Obama was, for her, a significant milestone and a joyful occasion, according to Baker, a teacher in Moretown.

"Paij wanted the world to celebrate diversity," Baker wrote. "Really celebrate it — not just tolerate it."

Paij ended her life on August 18 at the age of 77 — swallowing a "potion," to use her word, in her Montpelier home. She obtained it using Vermont's "death with dignity" law, which allows a person who is terminally ill to hasten death. Complications from diabetes had forced her to undergo daily dialysis treatment, which she did for about a year. After stopping treatment, she lived for two more months before deciding it was time to die. Paij donated her body to medical science, and asked Baker to accompany her remains from Montpelier to the University of Vermont Robert Larner College of Medicine in Burlington.

"She was a woman who believed that our lives are self-directed," said her daughter, Denise Bailey, a lawyer who lives in Montpelier. "We fight for our rights. We support the people we love. She planned her death to include as many people who loved her as possible."

Paij was born Panchita Anne Wadley on January 7, 1939, in New Haven, Conn. She grew up in that city, one of six siblings in a family of activists. Her father worked in a factory; her mother raised the kids and cleaned houses. The Baptist church was a central feature of the family's life.

Paij married as a young woman and had four children of her own before separating from her husband, Richard Bailey.

In the mid-1970s, she moved to central Vermont to study social ecology at Goddard College. Paij found her niche and stayed, said Denise, her oldest child. In Vermont, she came out as a lesbian, recognizing an identity she always knew was hers, she told her daughter. Coming out was a matter of finding an "affirming community."

Not everyone was supportive. "Her life was not easy, because of discrimination against people of color and against lesbians," Denise said. "My mother was very outspoken, so she called racism out whenever it occurred. She got a reputation for that."

Yet in a rural, predominantly white state, Paij touched and befriended scores of people through the life she made as a teacher, community organizer, singer, board member and activist. A 20-minute walk through Montpelier could take 90 minutes if you were walking with her mother, her daughter recalled. Everyone wanted to stop and talk to her.

"She was one of the most fun people I know," said Denise. "She was always very feisty and fiery. If she had an idea, she could organize something in half an hour."

Paij's work encompassed a range of issues and organizations. She cofounded the Vermont's Anti-Racism Action Team and its Reading to End Racism program; she was the first coordinator of the LGBTQA Center at the University of Vermont; she was a board member of the Peace & Justice Center in Burlington and Vermont Access to Reproductive Freedom; she did antiracism trainings with the RU12? Community Center (the precursor to Pride Center of Vermont); and she was active with the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom and the Raging Grannies.

Paij's activism is best understood as a whole and cohesive endeavor, suggested Rachel Siegel, executive director of the Peace & Justice Center. "Those groups don't seem disparate to me, including all the work she did around queer rights. It's all connected in that it's anti-oppression work."

In classrooms and workshops, Paij was adept at facilitating discussions centered on issues that can be particularly challenging to address, said David Shiman, emeritus professor of education at UVM.

"Paij could engage and challenge people around racism issues in a way that would draw people in, rather than push them away," he said.

About a dozen years ago, Paij helped organize an event that honored Juneteenth and Stonewall. The dual celebration marked the 1885 commemoration of the end of slavery and the 1969 Greenwich Village uprising that helped galvanize the gay rights movement. The event featured a big soul-food dinner in Burlington City Hall Auditorium.

"We wanted to make sure people understood that people of color had been standing with queer people for generations, and that it's important for queer people to also stand with people of color," said Christopher Kaufman Ilstrup, a philanthropic adviser at the Vermont Community Foundation and former director of RU12?.

"She was an amazing teacher for a generation of young activists," he said.

Last summer, Paij planned one final event — a celebration of her life that took place outside her apartment building the day before she died.

The last song to play was Patti LaBelle singing "Over the Rainbow." Wadley-Bailey danced to the song in the garden. Then she danced her way inside and upstairs to home.

— Sally Pollak

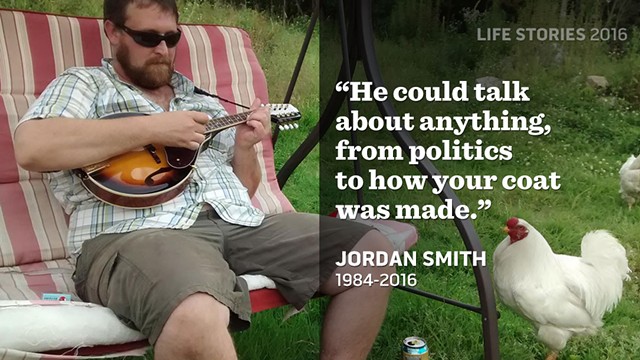

Jordan Smith, 1984-2016

Lamoille Ambulance Service EMTs Matt Lucier and Jordan Smith were partnered on a busy 24-hour shift. The phones were off the hook with unusual calls — fights and drunks and psychiatric meltdowns. En route to an incident, Lucier looked out the window, wondering why the night had gone mad. A huge moon lit up the sky. "Oh, it's a full moon," he said, turning to Jordan. "Must be why people are acting so crazy."

"Nope," Jordan said, grinning. "It's not a full moon."

Lucier pointed to the sky.

"Not full," Jordan repeated. "It's a waning gibbous."

Lucier assumed Jordan was bullshitting. They argued for 20 minutes until Lucier's iPhone confirmed that it was, in fact, a waning gibbous.

Jordan just nodded, with a told-ya-so grin.

That's when Lucier realized something all who knew Jordan learned early on: You don't win arguments with Jordan Smith. When the Groton native took an interest in something — astronomy, rare-breed chickens, raising goats — he studied it with fervor. Even on topics he knew little about, he'd talk anyone under the table.

"Everything that guy ever told me sounded true," recalls Scott Lavertu, who worked with Smith at the Groton Volunteer Fire Department* — one of several fire-and-rescue units Jordan was part of over the years. "He could talk about anything, from politics to how your coat was made."

Lavertu was part of the search party that looked for Jordan on March 4, after he went out for a late-night snowmobile romp and didn't return. Lavertu and fellow firefighter Phillip Palmer — who had known Jordan his whole life — followed snowmobile tracks to a hole in the ice on Ricker Pond, where the 31-year-old had released his final breath.

It was a sudden and tragic end to a life that friends, family and colleagues describe as "out of the box" and "not fitting the mold."

Even before Jordan was born, Brent and Pam Smith sensed that their fourth and youngest son would be different. "There was something about him," Brent said, speaking with Seven Days earlier this month. "I think you had the same feeling," he added, looking across the table at his wife.

Pam nodded. Jordan grew from a precocious chatterbox child into an impertinent teen, well-known to school and local authorities. His parents thought, Maybe "different" means he'll end up in jail.

Jordan never wound up behind bars — he had run-ins with the law but managed to talk himself out of some 15 speeding tickets.

And if he was happy to contradict anyone, Jordan did so with disarming spirit and a ridiculous, unforgettable laugh. "Jordy could work with anybody," recalled Dorothy Knott, a member of the Groton-Ryegate volunteer FAST (First Aid Stabilization Team) Squad ambulance service, which Jordan was leading at the time of his death.

Indeed, Jordan worked with lots of people in his various professional stints as a cook, car salesman and electrician. Emergency services were one constant in his life — family was another.

As a creative jack-of-all-trades, Jordan could have built a life anywhere. But he chose to live a mile from his parents and across the road from his brother, Aaron Smith. When he met Sara Bissell in 2002, he committed instantly and ferociously. The couple married in 2005 and remained together through several homes and dozens of hobbies and jobs.

In September 2015, Jordan parlayed his experience as a journeyman electrician into a teaching job at River Bend Career & Technical Center in Bradford. "When he got [that] position, he'd found his home," his father recalled. "He'd found exactly what he wanted to do for the rest of his life."

Jordan's good-humored empathy for all made him a great mentor. It also helped him recruit new members for the FAST Squad. He knew that recruiting youth was vital to ensure effective emergency services in his aging community.

At River Bend, 17-year-old Lilian Colby recalled meeting Jordan on a break between classes. "I was getting a soda from the vending machine," she said, "and I see this guy cantering down toward me." Who is this person? she thought.

Before she could ask, Jordan introduced himself. "I'm on the FAST Squad," he said. He'd heard she wanted to join but was intimidated by the group's older, longtime members. "Don't worry," he said, "We'll protect you."

A few days later, Colby asked for an application. Fast-forward a year, and she's one of the squad's most dedicated volunteers.

At Lamoille Ambulance, Lucier credits Jordan with his career. "He's probably the reason I'm still an EMT," Lucier said. He recalled falling behind on paperwork on a busy shift. Afterward, Jordan spent hours guiding him through the reports, clarifying the process with a mantra: "His big thing was KISS — 'Keep It Simple, Stupid.'"

Jordan's friends and colleagues continue to look to him for advice — in Groton and beyond, cars bearing "What would Jordy do?" bumper stickers recall his unflappable approach to work and life. Now, when faced with a tough situation, Lucier asks himself that question.

The answer is always the same: "He'd handle it with a smile on his face and a positive attitude," Lucier said. "And then it's like, OK, let's give that a shot."

— Hannah Palmer Egan

Correction, January 10, 2017: An earlier version of this story conflated the names of two sources for the story. Their names are Scott Lavertu and Shaun "Stetty" Stetson.

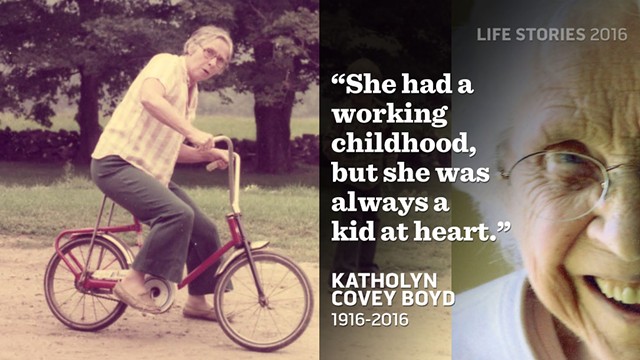

Katholyn Covey Boyd, 1916-2016

Katholyn "Kay" Boyd spent all 100 of her years in Vermont. Her life story illustrates many of the changes that have taken place over the last century as the state has shifted from a place filled with one-room schoolhouses and small-scale dairy farms to a landscape dotted with ski resorts and ravaged by Tropical Storm Irene.

The youngest of 10 children, Kay grew up on her family's dairy farm in West Brattleboro. Her education stopped after the eighth grade. She met her husband, Verne Boyd, at a local square dance and moved with him to his family's farm in Wilmington, two towns over. The couple raised two children, Carl and Ada.

"We were basically a subsistence farm," Carl explained. "They lived with what they had. They didn't owe anybody any money; all the bills were paid; we had a place to live and plenty to eat."

Bronchial asthma, also known as "farmer's lung," limited Verne physically most of his life, so Kay picked up the slack. She milked cows, cut hay, drove tractors, loaded hay bales, and boiled sap for syrup to sell.

"It was a tough life and required a lot of effort on her part," recalled Carl. "But she was always there. I never heard her complain."

In fact, Kay retained a whimsical, mischievous spirit — her obituary described her as "an incurable prankster."

"She had a working childhood," said Carl, "but she was always a kid at heart."

Kay loved dressing up for Halloween, he noted, assembling outfits from the trove of clothes and items collected in their old farmhouse. For reasons no one entirely understood, she would sometimes bust out her costume again on Thanksgiving. And she enjoyed tormenting her young nieces and nephews when they visited. At night, they were always a little nervous about setting out on the barely illuminated walkway to the Boyds' outhouse — when they had to go, Kay would scurry into the attic, open a window, drop a boot behind them and laugh when they ran away terrified.

When kids gathered in the yard in the summer to play hide-and-seek, a sole front porch light illuminating the rural blackness, they could always count on Kay to enter the fray.

And though some farmers, desensitized by owning livestock, have little interest in household pets, Kay doted on a menagerie of cats and dogs. Among her favorites were a terrier named Vickie and a black cat — jokingly called Misery — that had six or seven toes on each of its front paws.

Money was always tight, but the Boyds made sure their son had a car when he was a teenager and was able to go to college.

The death knell sounded for the Boyds' dairy farm in the 1960s, when milk processors no longer wanted to receive milk in 40-quart cans. They began to insist that farmers install large tanks in their barns to hold milk until a truck could come and pick it up. The new tanks were pricey and needed to be cleaned with gallons of hot water. But back then the Boyds didn't even have hot water for their home.

So they sold their 50 cattle and, along with their closest neighbors half a mile away, went into an entirely different business. They built and ran the North Star bowling alley, providing a venue for weekend gatherings and birthday parties in an area that had relatively few social options.

With her husband's health failing — Verne died in 1977 — they sold their stake in the bowling alley. She supported herself by picking up work at shops in Wilmington and Brattleboro and lodges at Mount Snow resort in West Dover.

Kay continued to show up at local square dances into her mid-seventies. And she played in candlepin bowling leagues into her nineties, rolling the two-pound, palm-size ball with a trademark style.

"She rolled a real slow ball, but she was very accurate," said North Star Bowl's current owner, Steve Butler. "She was very, very good."

In late summer 2011, Tropical Storm Irene flooded the bowling alley. At first, Butler was unsure if he would ever reopen. When he finally did, in 2012, there was only one person he wanted to roll the ceremonial first ball.

Kay was by then confined to a wheelchair, but she didn't hesitate to accept the invitation. With an onlooker capturing the moments on video, she crept toward the lane, leaned as far forward in her chair as she could without falling over, swung a tiny blue candlepin ball between her legs and set it off on a slow trip down the center of the lane.

— Mark Davis

Osman Bulle Ibrahim, 1949-2016

This fall, while attending a wedding in upstate New York, Osman Bulle Ibrahim fell ill. His relatives say the 67-year-old Somali Bantu elder — known among his community as Osman Bulle — was rushed to the hospital when he returned to Burlington on October 2. He died early the next day, leaving behind his wife, Halima Yarrow, and five children.

No obituary appeared in the newspapers, but, as news of his death spread through the Somali Bantu community in the U.S., approximately a thousand mourners offered their condolences. Some traveled to Vermont from across the country to pay their respects. For about a week, his family and neighbors in Burlington's Old North End put up visitors from as far away as Arizona and Texas.

Most of these out-of-state visitors had known the Bantu leader since they were refugees in Kenya. Osman's teenage son, Abdisalan, doesn't remember much from that time. The Burlington High School senior was only 6 years old when his family resettled in Vermont in 2004. He's heard about those years, though, and calls his father "a great man" and "a leader."

Khadija Osman, an older relative, remembers more of his legacy. "He used to help people come to America," she explained through an interpreter.

Osman Bulle was born in Somalia's Middle Juba state. A high school graduate, he worked for the department of agriculture. When civil war broke out in 1991, the Bantu, an ethnic minority who had long faced discrimination and marginalization, bore the brunt of the violence. Osman was among those who fled to the Dagahaley refugee camp in the Kenyan town of Dadaab.

Dagahaley was divided into blocks, with some 500 people living in each one. Osman was one of several block leaders. He attended meetings, distributed food and goods, and solved disputes.

"He was like a village leader," said Mohamed Abdi, former executive director of the Somali Bantu Community Association of Vermont.

The people in charge of the blocks were usually chosen based on one of three criteria: level of education, ability to speak English and leadership skills, Abdi said. Osman spoke little English, but he knew how to lead and held the position for a decade.

"I grew up under his leadership," Abdi noted.

Daniel Van Lehman, who was a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees field officer in the Dagahaley camp between 1992 and 1994, said discrimination against the Bantu by the Somali clan continued in Kenya. As a block leader advocating for Somali Bantu human rights and protection, Osman would likely have been threatened or subjected to intimidation, he noted.

"Many Bantu just kept their heads down and just got by in the camps," he wrote in an email. "Bantu representatives like Osman needed courage to carry out their work."

Despite the harsh living conditions at the camp, Osman demonstrated his entrepreneurial skills and thrived. He ran a small restaurant where people could drink tea and eat samosas. His nephew, Noor Bulle, said Osman was generous with his customers and never demanded payment. Osman later opened a convenience store in the camp that sold candies, sugar and tea.

His most pivotal role was helping Somali Bantu to be considered for resettlement to the U.S., a process that started in 2000. Osman was the conduit between the camp leadership, the UNHCR and international agencies, and his community.

The elder conveyed accurate information about the process to his people. He made sure they got to their interviews on time and were notified of the results. He encouraged families to learn conversational English and attend orientation classes. For those who failed their interviews, he fought for them to be given a chance to reapply, Abdi recalled.

The Somali clan tried to bribe Osman, said Noor. They wanted him to allow them to falsely claim Somali Bantu identity so that they could be considered for resettlement. But he said his uncle held his ground.

Osman used to tell them, "No, this is for my people. This is an opportunity for my people. I don't need your money."

He continued to be an advocate for his people after he moved to the Green Mountain State. In addition to working at IBM, Vermont Teddy Bear and, later, Walmart, Osman attended meetings with police chiefs and other community leaders to discuss the social challenges that the Bantu face.

Former Burlington Police chief Mike Schirling, director of BTV Ignite and soon-to-be secretary of the state's Agency of Commerce, described Osman as "a bridge" between Vermonters and their new Somali Bantu neighbors. As a community elder, Osman "helped to build relationships and understanding on topics that are often complex," Schirling wrote in an email. "That kind of work builds trust and helps to enhance community safety."

Mohamed Muktar, one of the hosts of the weekly news program "Somali Bantu TV," remembered Osman as a "storyteller." When the elder was at the broadcast studio, he shared stories about life in Somalia and the history of the Bantu people.

He urged Muktar to continue his work as a journalist, reporting and commenting on Somalia's current affairs. He would say, "Don't stop. It's going to benefit the younger generation."

— Kymelya Sari

Karen Karnes, 1925-2016

In 1998, potter Karen Karnes lost nearly everything. A kiln fire burned down her studio and the home she shared with her life partner, Ann Stannard, in the small Orleans County town of Morgan.

For her 2008 documentary Don't Know We'll See: The Work of Karen Karnes, Berkeley filmmaker Lucy Massie Phenix captured the artist sifting through the charred remains. In one powerful scene, Karen opens the kiln to reveal fired pots that survived the conflagration. "It's just how I was hoping it would look," she says.

Not that there was any doubt her work would endure. Collectors of her pottery include the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. During her long career, Karen garnered a Tiffany fellowship and a medal of excellence from the Society of Arts and Crafts in Boston, among other accolades. Governor Howard Dean listed them on her 1997 Governor's Award for Excellence in the Arts.

She and Stannard rebuilt their home in Morgan; Karen died there this summer at age 90.

Phenix said that Karen's pottery expressed fundamental humanity. "I always felt that her pots were really true," said the filmmaker, "that there was something unforced and un-self-conscious. They were just [an] outgrowth of something in her."

Karen's artistic drive emerged early. The daughter of Russian and Polish garment workers and union organizers, she grew up in the United Workers Cooperative Colony, aka the "Coops," in the Bronx. On her own, she applied and was accepted to Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts.

"She just kept making and following her own inspiration," Stannard said. "She was never influenced by other people or what they wanted or needed."

Karen began working with clay after meeting her future husband, David Weinrib, at Brooklyn College. In the late 1940s, the couple lived and made ceramics in a tent in Strasburg, Pa., and then traveled to Sesto Fiorentino in Tuscany.

One piece Karen made in Italy appeared in a recent nationally touring exhibition, "Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957." Karen and Weinrib were potters-in-residence at that North Carolina experimental art school from 1952 to 1954, working alongside artists Josef and Anni Albers, John Cage, Merce Cunningham and Robert Rauschenberg, among many others.

"Karen's work is a perfect marriage of Asian aesthetics and fidelity of material, a quietness, with a really modernist sense of form and purpose," said Massachusetts potter Mark Shapiro, who edited A Chosen Path: The Ceramic Art of Karen Karnes. "I think she might be one of the really great examples of those two tendencies in postwar culture."

Karen was also an early pioneer of salt-glaze and wood-firing techniques. Her organic works certainly differ from the abstract-expressionist sculptures of her Black Mountain contemporary Peter Voulkos.

"There were a lot of men of that period who were the loudest guys in the room," Shapiro noted. "Karen was always really quiet — and yet she was at the forefront." And she didn't succeed through political maneuvering or ladder climbing. "Her only strategy was to listen to her inexorable inner creative voice," he said. "It's a very moving and unusual thing."

As Black Mountain College began to dissolve in the mid-'50s, Karen cofounded the Gate Hill Cooperative in Stony Point, N.Y., and remained there 20 years. During that time she gave birth to her son, Abel, and separated amicably from Weinrib. Karen supported herself and Abel by selling her pottery.

In 1979, she and Stannard, a British artist, moved with several friends to Danville, Vt., and homesteaded off the grid. In 1983, the two women established their own studios and home in Morgan, where Karen worked, read and generally kept to herself. "Karen was a very inner, silent kind of person," Stannard said.

Though she never taught formally, Karen was an influential mentor. "She was very important to young students — young women particularly," Stannard noted. "She didn't do teaching as such — she earned all her living through her clay. [But] she would give them a lot of time when she met them at shows or craft fairs. And people would come to the house to speak with her."

Karen was a role model not only for women. "We took courage from her," Shapiro said. "She stood for some kind of artistic fierceness and integrity that we all aspire to [but] can't quite embody. She never let anything stand in the way of her work.

"She was a feminist icon, as far as I'm concerned," he added. "But she would never say it. She just did it."

— Rachel Elizabeth Jones

Mike Witham, 1951-2016

The term "celebration of life" is often a euphemism for "funeral." For drummer Mike Witham, stricken with terminal esophageal cancer, it was a way to announce his final show.

Held at the Barre nightclub Gusto's, "Mike Witham's Celebration of Life While Still Living" on Sunday, September 25, was equal parts rock concert and Irish wake — with the notable exception that the deceased was not yet dead. Mike made an unusual entrance — the 65-year-old lifelong Vermonter was rolled in on a red Radio Flyer wagon with lit sparklers in his hands. And there was a loud rock band playing.

"It was surreal," said Mike's daughter, Jessie Foster, of the party. "There was a lot of love. But there was a lot of sadness, because we knew we were getting toward the end."

Foster is the only daughter among the drummer's five children from his two wives. She estimates that between 150 and 200 people attended. Many had been Mike's bandmates at various points over the years, including members of the Guys, the Fantastix, the Cheever Brothers and his most recent outfit, Donna Thunders and the Storm, to name a few. Other notable local musicians in attendance were country singer Tim Brick, rebel rocker Jimmy T. Thurston, drummer Jeff Salisbury and bluesman Ray "Blind Man" Burke, among many others.

"My dad's No. 1 phrase was, 'Rock-and-roll never forgets,'" said Foster. "Rock-and-roll doesn't forget. We came together to celebrate him and good music. That's what musicians know how to do."

And it's exactly what they did. The party featured a 50-50 raffle to benefit cancer research and a presentation to Mike of cymbals signed by attendees. But the centerpiece of the evening was the epic, nightlong jam session onstage. And the highlight was when Mike overcame the physical debilitation from his disease to man the kit one last time.

He managed to play a handful of tunes that night — no small feat for someone in the very last stages of cancer. At one point, Foster noticed her father uncharacteristically lagging behind the beat, clearly tiring. She ran to the back of the bar to grab his good friend and longtime collaborator, guitarist Kurt Pearson, and ushered him to the stage.

"Kurt plugged in and it was like a surge of energy," recalled Foster. All of a sudden, Mike was back in the pocket. "My dad's face lit up and he got right back on beat," she said, adding that, at the end of the tune, he begged, "One more, one more!"

"It was like putting a wilting flower in a vase of water," said Donna Moran, the lead singer of Donna Thunders and the Storm. "He just sprung back to life."

"Music can really revive a person," said Foster.

She called the party Mike's "last moment of fame."

"It let him know what he meant to a lot of people," she said. "And not everybody has the opportunity to do that. He paved the way for a lot of musicians. And they told him that."

Mike was a fixture in the central Vermont music community for decades, having played his first gig at age 11. He ran a music shop, Witham Music, out of his home in Barre for 35 years. He taught drums and played in countless bands. He was also an artist and an avid collector of everything from old parade drums — some dating back to the late 1800s — to World War II memorabilia. His collection was so impressive that Moran describes his house as a museum.

"He was a borderline hoarder," Foster joked. "Oh, and he collected hats. So many hats."

"No one had style quite like Mike," said Moran.

"He would describe himself as an entertainer," said Foster, when asked to characterize her dad. "He was an artist through and through. He walked to the beat of his own drum, and he created that beat."

It seems he did, even posthumously.

Mike went to the great gig in the sky, drumsticks in hand, on October 17. His memorial service was held on October 29 at the First Presbyterian Church in Barre. It was called, fittingly, "The Final Curtain Call." And here, too, Mike made an unusual entrance.

"He said he wanted to be late to his own funeral," explained Foster with a laugh. To oblige the request, she and the family waited a few minutes past the funeral's appointed start time. Just when mourners were beginning to get fidgety, they brought Mike's ashes into the sanctuary — carried inside a snare drum.

— Dan Bolles

Dr. Henry Michael Tufo II, 1939-2016

Carleen Tufo always told family and friends she'd never marry a doctor. That is, until a junior medical student walked into her patient's hospital room — she was a pediatric nurse in Chicago at the time. The med student discovered that the boy, who was about to undergo surgery, had a heart murmur. Even the doctors had missed it. Had the surgery proceeded, the defect likely would have killed him.

"That's when I realized he was brilliant," recalled Carleen of Henry Michael Tufo II, who became her husband of nearly 53 years.

Colleagues, patients and friends remember Dr. Tufo as a gifted diagnostician of difficult medical problems, whether afflicting individual patients or the entire health care system. Trained in an era when physicians were often disparaged for becoming administrators — as University of Vermont Medical Center CEO John Brumsted put it, "going to the dark side" — Henry considered it "almost a duty" for physicians to assume those leadership roles.

Henry, who died October 19 at age 77, played a seminal role in reforming Vermont's health care delivery system, first at the University Health Center, which he led for 24 years, then at health care software company IDX Systems. But throughout his career at the highest echelons of Burlington's medical establishment, Tufo remained committed to his first love: treating patients. He continued to do so until his diagnosis of Parkinson's disease in 2008.

"Henry believed that it was impossible to stay on top of the psychological and systemic side of things unless you were in touch with patients," said journalist and health policy analyst Hamilton Davis, the doctor's longtime patient and friend. "He was determined to do that, and no one ever could talk him out of it."

Henry was born in Chicago on July 5, 1939, to Italian immigrants. Early on, he seemed destined for a career on the stage, performing in school plays and, later, in radio and television shows including "The Gene Autry Show," "Super Circus," "One Man's Family" and "Hawkins Falls." However, his father's sudden death from a heart attack when Henry was 12 inspired him to become a doctor.

When Carleen and Henry met in 1963, she said neither was looking to get married.

"It took him five dates to kiss me," she recalled. "Six months later, we were engaged."

Henry enlisted voluntarily in the Army Medical Corps during the Vietnam War, after completing his residency at the University of Illinois. He served stateside until his honorable discharge in 1971.

According to Carleen, Henry's stint in the Army taught him that medical tests were useless if the results were lost or if physicians didn't follow up on patients. From then on, she said, he dedicated himself to ensuring that patients "didn't fall through the cracks."

In 1970, the University of Vermont College of Medicine recruited Henry to establish one of the first integrated health systems in the country. There, he adopted a holistic, patient-centered approach to care; patients could see and comment on their own medical records, which were written in simple laymen's terms.

"As a practitioner first and foremost, Dr. Tufo ... always put the patient, the family and their needs above all else," said Brumsted.

Often, those needs came before those of Henry's own family. His wife and kids said it was commonplace to wait for him to come home — or to join him on medical calls.

"I spent more nights sitting in cars in front of people's houses, or in the emergency room, or in the priest's room," Carleen recalled.

"That's just the way it was," added Tufo's son, Henry Michael III. "Dad was busy doing these things for his patients, and we just had to be patient."

Henry's daughter, Gabriella "Gabe" Tufo Strouse, insisted they weren't jealous of their dad's patients. "We knew how much he loved them, and he was also so present with us," she said.

Gabe has fond memories of racing wheelchairs up and down the halls of the hospital with her brother. Once her dad arrived home, the family had dinner together almost every night. Tufo would then read to his kids, often falling asleep by their sides.

Though as children Gabe and Henry Michael couldn't fully appreciate the importance of their father's work, after his death Gabe said she was overwhelmed by the outpouring of sympathy from his former patients.

"To this day, people come up to me and say, 'Your father saved my life,'" Gabe noted. "He really believed in his patients and took time to listen to them."

As for Henry's own diagnosis of Parkinson's, he "basically approached it as a challenge," said his son.

Just weeks before his death, Henry met with Davis at the former's summer cabin on Thompson's Point in Charlotte, where they talked health care policy for more than two hours. Though Henry was deeply fatigued, Davis said his mind was as sharp as ever.

It's a sad irony that what ultimately claimed Henry's life was a lymphoma, diagnosed too late for treatment. Gabe said it was the only instance when she felt cheated out of time with her dad.

"At the end, when he retired," she recalled, "he said, 'It was a great ride.' And I believe that."

— Ken Picard

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.