Vermont's tech economy is growing. It isn't Silicon Valley — yet — but anecdotal evidence suggests an increasing number of local tech companies are calling Vermont home. Ditto techie events, from hackathons to code camps, business pitch competitions to mini maker faires.

Advances in technology are playing a role in this shift — it's easier than ever to connect and share information in Vermont — but it's people who make the network work.

We talked with seven of them who've found their niches in various corners of the state's tech industry: schools, businesses, community organizations. We asked them what they're passionate about and why, and where they think Vermont's burgeoning tech scene is headed.

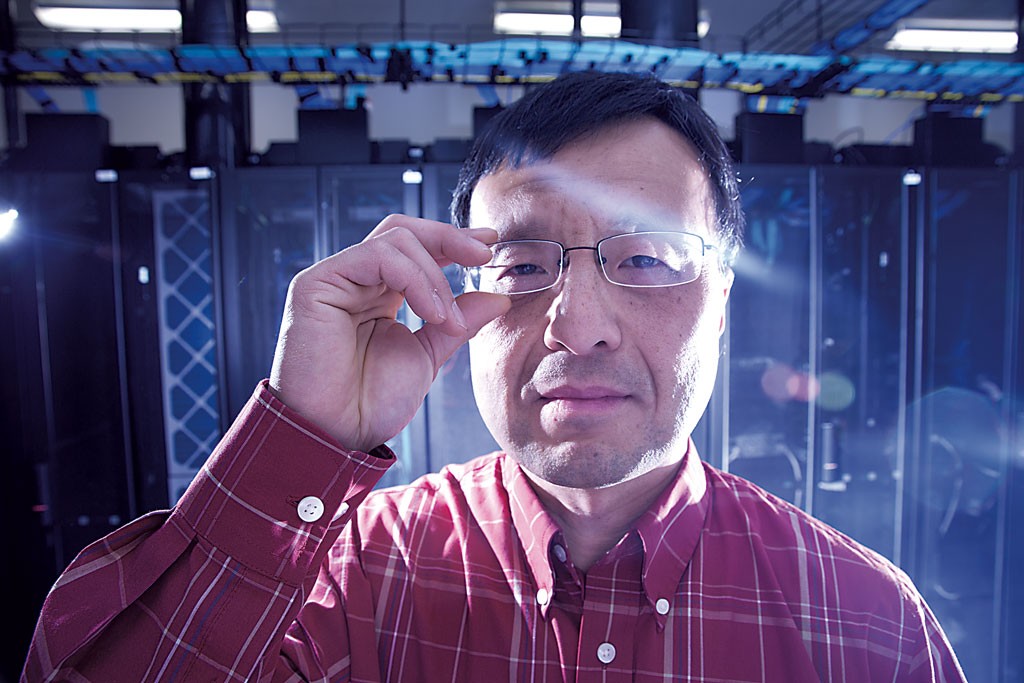

The Behind-the-Scenes IT Guy

Joe Ng, Mainframe and Operations Director, State of Vermont Data Centers

- Matthew thorsen

- Joe Ng

Walking into Joe Ng's office is sort of like walking into The Matrix. Not only is the room filled with stark, black, heavily whirring server stacks, but its digital arteries course with the 1s and 0s that hold everything together. "Everything," in this case, are most of the digital transactions carried out by the State of Vermont. If you're a Vermonter, your encrypted digital information probably passes hourly through one of the four data centers under Ng's supervision. But don't blame him for Vermont Health Connect — he's "not familiar" with the system architecture, though some of its data resides on his servers.

What are your primary job responsibilities?

Part of my responsibility is managing the four data centers for the state: two in Montpelier, one in Barre and one in South Burlington. I manage the data centers, the mainframe computer operations, and do tech support and services for the State of Vermont. I make sure the infrastructure is up and running, the power is on, the cooling is on, the servers are operating optimally.

What kinds of information are stored in these servers?

We have email for all state employees, information about benefits from the Agency of Human Services, the benefits from the WIC program. We also process checks for custodians and parents, data for the Department of Motor Vehicles, the Agency of Transportation, the State Treasury, the Secretary of State, the state libraries, the court system, the Department of Taxes, the Agency of Natural Resources. Most major agencies are represented.

What's the total amount of computing power here?

It's hard to say, because we use lots of virtualized environments. Basically, I can take things that I would run on five physical servers and run them virtually on one server. It's all done through software.

Are there particular challenges in working in tech in the public sector?

The challenge is always trying to keep up with the technology and trying to have the human resources and capital. There are more projects than we have people to work on them. Across industries, this is always a challenge, whether you are Microsoft or a small company.

I think there is always a challenge in teaching or having enough people in the STEM disciplines. However, I also believe we need more than a bunch of scientists and engineers. I believe we need to have painters and sculptors and writers and poets.

The Mountaintop Coder

Julie Lerman, expert in Microsoft's Entity Framework

- Matthew thorsen

- Julie Lerman

The world's leading expert in Microsoft's Entity Framework, a vitally important object-relational mapping tool, lives on a hillside in Chittenden County. A freelance consultant, Julie Lerman could have situated herself just about anywhere, but she loves to ski — which is lucky for the Vermont tech scene. Lerman was an early organizer of what's now the Vermont Technology Alliance, an industry trade group, and is a driving force behind the annual Vermont Code Camp at UVM.

Explain it to me like I'm 14: What exactly is the Entity Framework?

It's a tool within Microsoft's development framework, which is called .NET. Entity is .NET's tool for interacting with data from your applications. Relationship databases, which are the most classic databases, organize their data in rows and columns, but when we write code, we talk about things, and things have properties and meaning. An object-relational mapper allows you to think in terms of your application and then it will transform what you're asking for out of the database into the database's "rows and columns" language.

Besides writing books about it, how do you work with Entity Framework?

I help other developers and companies use it better as part of their software. I don't do the coding, but I help them understand better how to use it in an architecture. I also help them with data access.

How would you characterize the coding community in Vermont?

We have this really broad community of developers and we all do a lot of similar things. I love the Vermont Code Camps. They're really diverse and bring in the whole community. We're all friends, we all collaborate on engaging local developers and helping to teach. We're all geeks, right?

You write books, you teach online classes, you give conference talks. What compels you to share your knowledge with others?

I like making sure that people don't feel like they don't have access to information. Years ago, I was at a presentation. The thing that the speaker was teaching depended on understanding something else, and he totally glazed over the other thing. The presentation was recorded, and I went over that little part 20 times until I finally understood what he was talking about. It's not fair to assume people know things. I decided that I wanted to help those people who think, "Well, I don't know that thing, but I better not ask because it'll be obvious that I'm stupid." I just don't want to leave those people behind.

Software development has a reputation for being a bit of boys' club. Do you find that to be true?

It's so sticky, especially right now, with the whole Gamergate thing [a controversy over misogyny in the gaming community.] But here's what I want to say: I find that not to be true at all here in the Burlington area. Our community is so open and wonderful. As a matter of fact, most of the community leaders in our area are women. I'm also at a position in my life where I've got enough street cred that I don't think I'm experiencing gender bias anymore.

How do you encourage people to code?

We actually had a "Day of Code" here at my house, for my neighbors. We had kids, we had 60-year-olds. We had laptops and iPads all over the place. There are people who are just going to gravitate toward coding, no matter what. The important thing is to make sure that the doors are open.

The Academic

Maggie Eppstein, Professor and Chair of Computer Science, University of Vermont

- Matthew thorsen

- Maggie Eppstein

Maggie Eppstein has been at the University of Vermont, in one capacity or another, since 1983, starting as a grad student and working her way up to be chair of the Department of Computer Science. Her office bookshelves sag with computer-language manuals, many of which she uses her various interdisciplinary projects. In teaching the next generation of computer scientists, Eppstein is a linchpin in the state’s tech economy.

What are some misconceptions about computer science?

Most people have no clue what computer science is all about. Computer science is really the science of problem solving, usually using computers — but not always. Even the science of what is computable — by human brains or by computers — falls under computer science.

I actually work in an area called computational sciences. I am solving problems in science and engineering by developing computer algorithms that can tackle those problems. Most computer scientists work in very multidisciplinary teams on a whole variety of cutting-edge problems in science, engineering, business, medicine, defense, security. We have constantly streaming data coming from every corner of the Earth, and it’s computer scientists who need to be able to figure out how to make sense of that data, how to see useful patterns in it. It’s a very satisfying and creative area.

What are some of your current projects?

The project that I’m most excited about is one on which I’m working with associate professor Paul Hines in engineering. It’s related to the electrical grid. I’ve been developing an algorithm for rapidly finding nonlinearly interacting combinations of outages that lead to cascading failures. Together, along with grad student Pooya Rezaei, we’ve developed … new ways of mitigating such risks. We think this is going to be really important for thinking about more integration of renewables into the grid, more distributed power generation and being able to understand how to keep the grid stable. Of all the things I’ve done, I think this one has the most chance of actually making a big impact on the real world.

I understand you’ve done a lot of work to attract women to computer science.

Nationwide, only 12 percent of graduating computer scientists from Ph.D.-granting universities are female. Here at UVM, we went from 10 percent females in 2010 to 17 percent females last year. We’re really working to increase that.

I recently got a $650,000 National Science Foundation grant for scholarships for incoming computer scientists, with an emphasis on trying to recruit women and other underrepresented groups. We’re one of only 15 computer science departments in the U.S. to be part of the BRAID initiative: Broadening Recruiting And Inclusion for Diversity.

Have you noticed a recent uptick in student interest in coding?

At UVM computer science, enrollment has been up about 172 percent over the last four years. We’ve had a tremendous uptick. There’s an infinite need for computer scientists who can work on “big data” problems.

The Seed-Planter

Cairn Cross, Cofounder and Managing Director, FreshTracks Capital

- Matthew Thorsen

- Cairn Cross

The venture capital fund that Cairn Cross manages has been in the news lately for funding the new, Burlington-based social network Ello. But FreshTracks Capital has had a hand in the growth of many other Vermont companies, including the Middlebury marketing concern Faraday and Shelburne's EatingWell Media Group. Last year, the Vermont Technology Alliance recognized its contributions with a Tech Jam Ambassador Award. Cross, who recently organized a "Road Pitch" event in which investors on motorcycles visited small Vermont towns, calls himself "bullish" on the local tech scene, and not just because there's money to be made.

Why focus on investing in tech companies?

The tech scene in Burlington today is really strong. I think what happens with tech entrepreneurs more than probably any other entrepreneurs is that they can live and locate their businesses anywhere. If this is an attractive area to them, they can do world-class stuff here.

How can the local tech economy get even stronger?

From an economic development perspective, we tend to focus on the wrong things. I think we should focus on: If you wanted to live in Burlington, where else might you like to live? Boulder; Bozeman; Boise; Bend — the Bs! If I'm surveying the competitive landscape, I want to know what's going on in those places, why people would choose them over Burlington and what we can do to differentiate ourselves. I would spend my time more on that than worrying about how there's no sales tax in New Hampshire but there's sales tax in Vermont. The bigger problem is that people who work at Dealer.com like living in Burlington, but they might also like working for XYZ Corporation that's emerging in Bozeman, Mont.

What kinds of changes have you seen in Burlington's tech scene?

Today, you can go take a walk to the Karma Bird House, go to the maker space, see all the stuff that's happening. There's this buzz going on. All of these people, not all of whom are well-known or in positions in which they get to make decisions — they're all incredibly important to making the overall ecosystem work. That's what's so exciting. The tech pioneers of 20 or 30 years ago in Vermont were a lot more lonely.

You also teach business courses at UVM and Champlain College.

The reason I decided to get into the classroom was that I thought it would be a great way to connect with young potential entrepreneurs. It seemed to me that there were some interesting things going on in the local colleges, and the best way for me to get involved was to be right at ground level.

The other thing I've been involved with for a couple years now is being a coach for the LaunchVT competition. I enjoy the chance to spend an in-depth period, usually five or six weeks, with a team, polishing up their pitch. It's a blend of public speaking, theater and business savvy. I find all that stuff fascinating. It's a great way to study human behavior.

The Organizer

Maureen McElaney, Founder, Girl Develop It, Burlington

- Matthew Thorsen

- Maureen McElaney

The national nonprofit Girl Develop It has had a Burlington chapter since 2013. For one reason: Maureen McElaney. A quality assurance engineer for Dealer.com by day, McElaney also finds time to lead the local branch of GDI, where she supervises classes and social events designed to encourage women to learn software development. For many an independent-minded female coder, McElaney is a guiding light.

How and why did you establish a Girl Develop It chapter in Burlington?

I was involved in Girl Develop It in Philadelphia, where I grew up. I moved here, and I missed it. I was looking for something similar, but I didn't see a good place for people to go to an informal meet-up setting and learn. I missed the community of women, specifically. I asked around and met people like Julie Lerman. I asked them if this was something that Burlington needed, and they all said, "Yes, we need to do this."

What kinds of skills do you teach at GDI?

Some classes are more structured. People come in to learn a specific language or skill. For example, this month, we have a class on relational databases. People come in there not knowing anything. We also teach HTML, CSS, JavaScript — more common languages that people outside of tech recognize.

We also have monthly "Code and Coffee" nights. These are open-format. People can come and bring their projects, ask questions, meet the community.

Why should we learn to code?

More and more, it's becoming part of every job. Everybody needs a website, everybody needs to market to their customers, who are increasingly moving online.

Why should women learn to code?

It's empowering for women to learn that they're good at it. Coding is something, I think, that women in today's society weren't brought up to think they should be involved with. The number of women entering the industry is decreasing. Women are being driven out, and we need to change that.

How is that happening?

Many factors suggest women are not made to feel welcome in the tech industry, from hiring and talent retention practices not conducive to fostering diversity, to an obvious imbalance of women with technical backgrounds in power positions. Making a career switch into tech often has a high price of admission. There's a prevalent attitude that unless you're willing to work all hours of the night and spend all your free time learning new languages, you'll be left behind. Women need a strong mentorship network and access to training to feel like they have a chance at breaking in.

Have you found the local tech community to be welcoming?

Amazingly so. I came in here as a stranger with this crazy idea. I would go to meet-ups and talk to random strangers to ask if they would help me. Everyone resoundingly said yes.

What are some of the challenges of working in a small tech industry in a small state?

It's been really tough to find space for classes and events, affordable space in town that is accessible and has parking. That makes it hard for us to meet the demand in our community. We have over 500 members now, and I can still really only offer a class a month.

I also think that some of the coding groups are starting to get quiet. There are bursts of activity, but then a lot of quiet time. People tell me that Girl Develop It is the only thing that's regularly active. I hope that someone picks up the torch to do more. I wouldn't see it as competition, but as meeting a need.

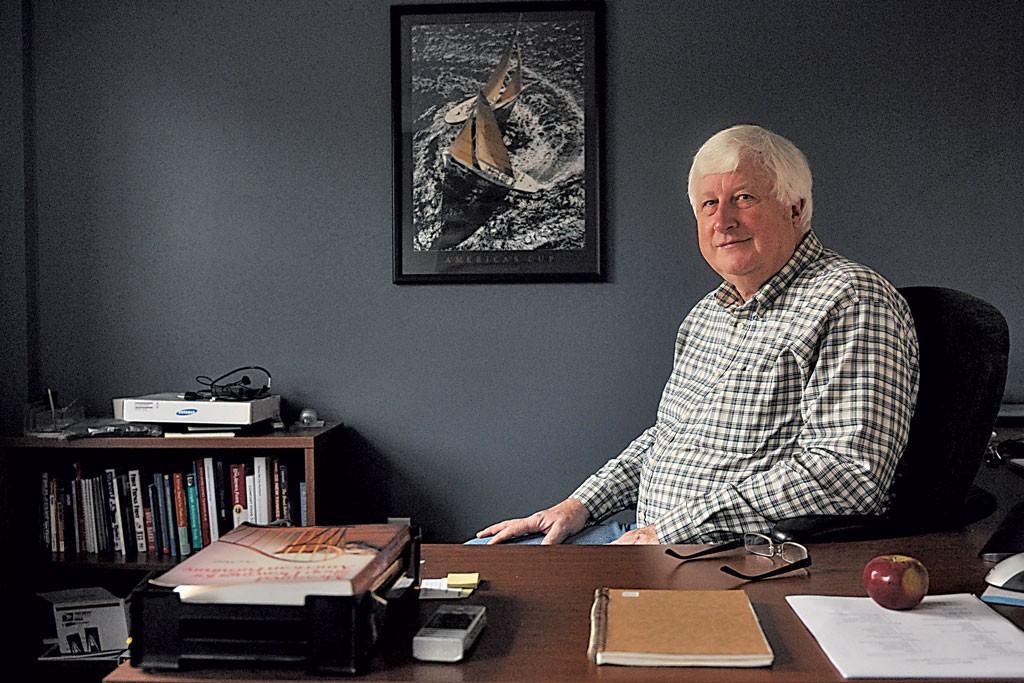

The Rural Entrepreneur

Dave Brown, President and CEO, MISys, Woodstock

- Sarah priestap

- Dave Brown

Dave Brown founded Manufacturing Information Systems in Woodstock nearly 30 years ago. From a small software company flying under the radar — until last year, there was no signage identifying the office — it's grown to 26 employees. Training and hiring local talent, Brown assembled a team that developed its flagship inventory-management software. The 67-year-old entrepreneur explains how creating an industry-leading product transformed the small, rural software company known as MISys — pronounced "my sis."

What, exactly, does MISys do?

If you were in the business of making baby buggies, our software would make sure that you had all of the pieces of the buggies at the right time; you don't need to have the wheels, for example, on day one. And having buggy wheels now, when you don't need them, is a waste of time and money. We say that other people's manufacturing software helps you maintain inventory; our software helps you maintain no inventory.

How did you identify the niche for your product?

I remember sitting down with the president of [my former employer, a computer company], asking, "How are we going to compete with IBM?" He smiled and said, "You don't compete with IBM. You find cracks in their business where you can live and make a perfectly good income." When I started the business, that was the idea: Find some crack that nobody else is going to fill. Be a friend to the bigger companies but do something that they need done but aren't going to do.

What are the challenges of running a tech company in a rural area?

Two things: the availability of talent and internet connectivity.

I like to hire local people. Why? Because local people are invested in the community and they're going to stay. It takes so long to train people; it's a huge investment. So we really need to be looking at the long haul. If you're running a fast-food joint, you don't really care if the workers come to work next week or not. But in our business, where it takes at least a year to bring someone up to speed, we're really concerned about the longevity issue. Unfortunately, Woodstock in particular and Vermont in general hasn't done a good job of attracting those kinds of people. I think everybody understands that. So we hire the best people, but we often have to bring them in from afar.

We're building software that assumes a 30 megabit-per-second symmetrical connection (download and upload speeds of 30Mbps) but that's not available outside of Chittenden County. You lucky Chittenden County people aside, most Vermonters have been saddled with slow dial-up, while the worst-performing service you could purchase in Japan was 100/100Mbps.

I see reliable, high-speed internet as the only way that I can survive in business and live in a place that I want to live in. There are a lot of places that I could go that have fiber-optic connections, but I don't want to live there. So I put up with what the lazy telcos have given us in the short term — which is inadequate, despite what the governor says. There has been some progress, though. Just this year, ECFiber and the Vermont Telecommunications Authority have decided to work on some projects collaboratively. One of those projects brings 1000Mbps internet just a mile away from our office. I'm trying to think about how many extension cords I could possibly buy.

The Future

Kirby Gordon, Junior, Montpelier High School

- Jeb Wallace-Brodeur

- Kirby Gordon

Montpelier High School's Kirby Gordon, 17, is known for his off-the-charts PSAT scores. But the junior also has a remarkable aptitude for writing computer code. "His Java is better than my Java," says Gordon's computer science teacher, Whitney Machnik. An affable, articulate young man, Gordon is representative of Vermont's next wave of tech leaders.

How did you get started with coding?

I was messing around with PowerPoint and I got frustrated with it because there's no interactivity. So I took up Scratch, which is a drag-and-drop programming language that's good for beginners. I got frustrated with that eventually, too, because there wasn't enough you could do with it. I taught myself Java and then also went to a few camps in summers to learn more Java. Last year, when I got serious about it, I took an online class to be able to take the AP computer science exam. [Gordon got a 5 on the exam, the highest possible score.]

What is it that you like so much about programming?

I like that you can have nothing on the screen — just a blank page. Then, by the end, you have lines and lines of computer code. Starting with nothing and ending up with a whole program. That part is satisfying: You know that if you get one character out of place, the whole thing falls apart. If you hit the RUN button and it works, you know that you've done it right.

What kinds of avenues have you found that let you explore your interest in computers?

I worked at [Montpelier web application company] Bear Code, which specializes in healthcare and voting. I went over there to learn more about programming in the real world. As opposed to "this is what I want to make," they'd tell me something to do and then I'd have to do it. Most recently, I was working on software that would attach itself to kids' social media and look for indicators of behavior that parents wouldn't approve of. So it would look for red cups in pictures, which would indicate that the kids were at parties, drinking.

What do you see yourself doing in 10 years?

I think I'd like to be doing something where I can use my skills in computer programming. I'd like to learn some other field of science but apply computer programming to it, maybe something in biology or chemistry. I like learning about how atoms bond to each other to form molecules. We see all this complexity all around us, but if you zoom way in, you can understand it with very logical rules about how things bond together.

If you could find a job like that in Vermont, would you stay?

If an attractive tech job opened up for me in Vermont, I would most likely stay.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.