- Courtesy Of Sugarbush Resort

- Filming the gondola

Charlie Brown remembers the first time he stepped into the Blue Tooth, a tavern on the Sugarbush Access Road in Warren. It was 53 years ago, and he was a 28-year-old from Philadelphia up for a ski weekend.

"The band was playing, there was a fire in the fireplace, huge icicles hanging from the roof all the way down to the ground, and I just went, 'Whew, I am in love," Brown recalled with a hearty chuckle.

Within six years, he owned a piece of the rock-and-roll joint and was a full-time Mad River Valley resident.

Brown's story is one that played out similarly for hundreds of other young, college-educated people who moved to Vermont in the 1960s and '70s to become "ski bums." Simply defined, those are individuals who move to a ski town, get a job that provides a ski pass as compensation, and then ski all winter — when they're not working or partying.

"An educated, potentially productive member of society," clarified Carl Lobel, who was a public defender in New Jersey before he moved to the Mad River Valley in 1975.

Win Smith, who left a plum job at Merrill Lynch to run the Sugarbush Resort in Warren, said the stereotypical ski bum has a "Peter Pan complex" — that is, he or she actively resists growing old.

As a sociological phenomenon, though, the group is generally overlooked and undercounted, because of another influx of transplants during the same time period. An estimated 40,000 back-to-the-landers and hippies flocked to Vermont during the free-love era, increasing the state's population by 15 percent. Last fall, the Vermont Historical Society curated an exhibit that documented the movement and how it changed the state.

Lobel, who still lives in Warren, found the exhibit lacking because it failed to recognize the contributions of his fellow snow bros — mostly white males from affluent families. "The ski bums that I knew were not motivated by idealism" like the hippies were, he acknowledged. "They just wanted to have a good time."

But the winter-sports lovers did shape Vermont's economy, politics and culture, he argued. The pejorative term "ski bum" belies the entrepreneurial drive of these individuals, many of whom stayed and made Vermont what it is today.

Is there a way to quantify their impact?

The modern ski industry is a major economic driver in Vermont. It brings an estimated $700 million into local economies and provides 12,000 jobs at ski areas, and another 22,000 indirect jobs to the surrounding communities, according to Parker Riehle, president of the Vermont Ski Areas Association.

Local legend has it that Tom Watson Jr., IBM's visionary president, opened the company's Essex Junction campus in 1957 to be closer to Stowe, where he owned a ski place. Walt Levering, a ski bum who came to Vermont in 1960, believes the rumor is true. Levering crewed on one of Watson's boats out of their shared hometown of Greenwich, Conn.

One winter, while Levering was working ski patrol at Stowe, he found himself on the ski lift with Watson. In the time it took to get to the top of the mountain, Watson had recruited Levering to work at the ski resort next door. Watson bought Smugglers' Notch in 1963.

"I just came up on a long ski weekend and never left," Levering, now 80, recounted. "I said, 'This is where I want to be.' And I said, 'How do I get a job?'"

Levering bounced around from one opportunity to another — mostly in public relations and real estate — before opening South Burlington's Econo Lodge and Windjammer Restaurant in the 1970s. He sold his business about 10 years ago but still lives in the area and skis at Stowe. His current wife, Carolyn, was formerly married to the late Peter Ruschp — son of Austrian-born U.S. ski legend Sepp Ruschp, one of the resort's pioneers.

Neither Levering's nor anyone else's ski-bum stories have been collected for posterity. Amanda Gustin, who curated the VHS exhibit, said the historical society hasn't examined the group.

Ditto the Vermont Ski and Snowboard Museum. The Stowe-based organization has hundreds of photos, artifacts and items from the era but hasn't held a ski bum-specific exhibit exploring the movement.

- Courtesy of Charlie Brown

A rare ski-bum reference appears in a forthcoming book by Gary Shattuck about the history of drug use and addiction in Vermont. Not surprisingly, it isn't flattering. In Green Mountain Opium Eaters: A History of Early Addiction in Vermont, Shattuck notes a spike in "drug complaints" between 1967 and 1968.

One explanation, in a statement from Vermont State Police Lt. Robert Iverson, was "the fact that Vermont now supports a large number of shiftless ski bums" and they, in turn, were corrupting Vermont's youth. He went on, "Many of them are characterized by their unshaven faces, filthy clothes and generally unkempt nature."

For this article, Seven Days focused on a collection of still-colorful characters in the Mad River Valley. There, three ski resorts — Mad River Glen, Sugarbush and Glen Ellen — operated within a few miles of each other during the ski-bum surge. That's not to say areas such as Killington, Stowe, Okemo, Burke and Jay Peak don't have their own unique histories; they do. But recounting them all would fill a book.

The era lives on in those who continue to embrace it. At 90, Henri Borel still skis at Sugarbush. The fine-dining restaurant he opened in 1964, Chez Henri, helped put Vermont on the culinary map, along with the valley's the Common Man, Sam Rupert's, the Phoenix and Tucker Hill Lodge.

On a recent Thursday morning, as light snow fell on Lincoln Peak, 79-year-old Al Hobart was one of 20 people who showed up to participate in the Sugarbush Racing Club's weekly timed "ski-bum" slalom competition. With wide, graceful turns, he kept up with the best of them.

Hobart is a legend in his own right. During a ride up the chairlift, he recounted how he moved to the valley in 1963 after getting a business degree at Dartmouth College. Taking note of how many local kids left the area to attend Burke Mountain Academy, in 1973 Hobart founded what became Waitsfield's Green Mountain Valley School. To this day, GMVS churns out Olympic champion skiers. In 2008, the Vermont Ski and Snowboard Museum inducted Hobart into its Hall of Fame.

John Egan, another skiing great, also calls Sugarbush home. He moved to the area as a ski bum in the 1970s before being noticed by Warren Miller, who featured the daredevil in several of his films. Egan still offers private adventures on the mountain and will be inducted into the U.S. Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame later this year.

"Back in the day, the valley was a regular mixing bowl," said Cindy Carr, who moved to the area in 1969 and now owns one of its most successful real estate agencies. "You would go to parties and rub elbows with farmers, tycoons, the owner of the ski area and famous people. Social lines were blurred, and people loved it. Things are more stratified now ... but the same spirit still runs through it."

Vermont's golden age of ski bumming is arguably over. People still do it — just not in the same numbers. Smith, who bought Sugarbush in 2001, surmised that the economics no longer work. College kids leave school with too much debt to be able to work for just a ski pass or the type of wages offered for a job running the lifts. Himself a middle-aged ski bum of sorts, Smith said he has trouble filling all available job openings each season. Using J-1 visas, this year he hired nearly 20 young adults mostly from Peru, who work in food and beverage and housekeeping at the resort.

"They have an interest in learning to ski and snowboard but don't have much experience," Smith said. "Maybe they'll be the next generation of ski bums."

- Courtesy Of Charlie Brown

- Blue Tooth employees

Like Smith, Brown of Blue Tooth fame turned his back on the corporate world to spend more time on the slopes. In the fall of 1964, a few months after his first visit to the Mad River Valley, he was up for a job as vice president of computer operations for Revlon. During the final interview, on the 35th floor of a Manhattan skyscraper, he got a tough question.

"What are you going to be thinking about when the snow starts falling in December?" said Brown, paraphrasing the insightful interviewer, who knew he was a skier. "And I went, Oh shit," Brown said with a deep, throaty laugh. "So I looked at him, I looked out the window, I looked at him, I looked out the window, and said, 'Thank you very much,' and walked out the door. And that was the best decision I've ever made in my life."

Here are several skiers who were lured by the Green Mountains — and never left.

The College Sweethearts

- courtesy of Sparky Potter

- Peggy and Sparky Potter

Peggy and Sparky Potter were four years apart at St. Lawrence University when a common destination — the Mad River Valley — brought them together. Sparky, a senior, had the wheels.

"It's a three-and-a-half-hour drive, so you get to know people pretty well," he said with a mischievous smile during an interview at the Waitsfield offices of Wood & Wood, the sign-making operation he started 45 years ago.

Peggy had grown up skiing in the valley, and she had a boyfriend at the University of Vermont — until she took that road trip with her future husband.

- courtesy of Charlie Brown

- Sparky and Peggy Potter with Charlie Brown

But the area was new to Sparky. He was headed there to ski because his college frat had rented a house in Warren from architect David Sellers — "a plywood vertical building with 16 bedrooms that moved in the wind," as Sparky recalled it. "It was wild."

After graduation and a short stint in Aspen, Sparky landed a job on the Sugarbush Ski Patrol and made the valley his home.

"I think there were a lot of people who had a desire to get out of the cities," he said. "Everybody had seen enough of Warren Miller's movies by then to kind of get that there was another lifestyle out there."

After some "vagabonding," Peggy followed him, and in 1974 the couple married and began building the funky Fayston home where they still live.

Peggy started working in restaurants, including the popular Sam Rupert's Restaurant, while Sparky ski patrolled and started his wood-carving business. The couple palled around with a core group of 35 to 40 young people who had also moved to the valley to give ski bumming a shot.

"It was a total privilege to be a part of that rat pack, to have that exhilaration in life that you never want to lose," said Peggy. "Whether it was corn-snow days in March or shooting tequila between runs — that's what we did. No one had to be at work until 4:30 or 5, so there was plenty of time to recover from whatever you'd done during the day."

Sparky's woodwork eventually began to get noticed. One of his first clients was Sugarbush — he'd become friendly with owners Damon Gadd and Jack Murphy, who hired his company to create its signs.

- courtesy of Sparky Potter

- Sparky Potter skiing

"A lot of the people I'd meet on the chairlifts would come back and become clients," Sparky said. "People I skied with. You do a few runs together and, the next thing you know, you have a pretty solid connection for life."

Around the same time, the Potters teamed up with Charlie Brown, who hired them to help him put on his "Academy Awards" show at the Blue Tooth, where patrons would dress up and come to see who would win "bartender of the year" or the coveted "shoe full of shit" award. "There was no station in life that was too high or too low to be included," said Peggy, who helped produce the show. "It was across the board — everybody."

The Potters and Brown were avid photographers and, along with pal Irving "Rush" Rushworth, they eventually started Dream On Productions. They'd set photo slide shows to music and travel throughout New England, and sometimes beyond, putting on their show in nightclubs.

The company eventually got into the public relations business, running campaigns for Sugarbush and R.J. Reynolds Tobacco, which sponsored speed-skiing events; and they signed on to shoot the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, N.Y.

After the Games, the Potters, Brown and Rushworth presented their multimedia slide show at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York City during a celebration for the gold medal-winning men's U.S. hockey team.

The group also worked for Norwegian America Cruise Line and Princess Hotels, business opportunities that paid them to travel.

- courtesy of Sparky Potter

- Sparky and Peggy Potter

Eventually, Brown started his own business while the Potters let Dream On fade away. Peggy got into decorating wooden bowls, while Sparky's sign business took off.

He's made signs for ski resorts across the country, including most of the major ski areas in Vermont. Sparky also counts Ben & Jerry's, Vermont Teddy Bear and several universities among his clients.

"It's all one big petri dish that just blossomed into so many things," Peggy said of the era in which the couple came of age. That includes their three kids. The middle one is rock star Grace Potter.

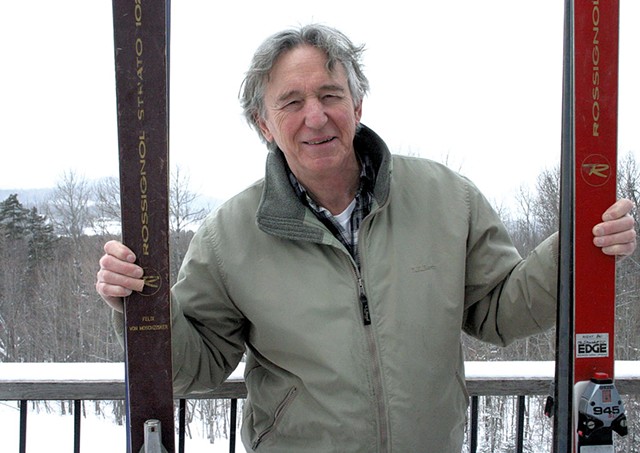

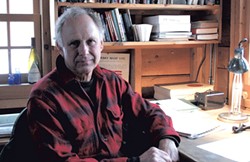

The Chronicler

- Sasha Goldstein

- Felix von Moschzisker

Years before the New York Post created its gossipy Page Six, the Mad River Valley had a scandal sheet of its own.

Felix von Moschzisker came to Warren to ski but spent much of his time compiling material for the Scene Scene, his weekly, single-page newsletter. He sold advertisements along the outer edges, while the text, which featured the gossip and local miscellany of the week, read like a string of headline haikus:

"Arthur Williams got hit by a truck tire. Jimmy Boyce sat in Bilbo's and grumbled to himself. Dave Sellers got a brand new red arctic parka."

The newsletter was von Moschzisker's own form of social media, decades before Facebook.

It was a 1970 wedding in East Warren, on a hill overlooking Lincoln Peak, that convinced him to leave a New York City job at LIFE magazine.

"We arrived in the darkness, and, in the morning, there was this view. It was stunning," von Moschzisker recalled. "I came up here and saw another way of living."

His marriage later fell apart, and he ended up living with friends on Prickly Mountain. That had become an enclave for architects, including Sellers, who built wacky homes. And that's where von Moschzisker started his seasonal newspaper.

At first the advertising in the Scene Scene didn't bring in much money, so von Moschzisker slummed it. He'd rent a room in a friend's home or house-sit. During one desperate winter — his second in town — he lived in an uninsulated shed with a woodstove.

"All I knew was, I wanted to stay up here and live in this environment, but I didn't know if I would be able to continue to do it," von Moschzisker said.

- Courtesy Of Felix Von Moschzisker

- Felix von Moschzisker

To collect material for his newsletter, he drove around the valley in a rainbow-striped Volkswagen Beetle. He'd write about someone getting a haircut, or someone spotted throwing back beers in the bar, or yet another who'd just picked up some pot. He even included some short fiction stories.

"Felix was a minstrel for us all, the chronicler of truth — and fantasy — and everybody loved it," said Peggy Potter. "It was just what everybody dreamed it was, whether it happened or not."

The Scene Scene became wildly popular, and it became easier for von Moschzisker to sell advertising. Each Friday, he'd pick up 1,000 printed copies. Then he'd pop in to hangouts including the Blue Tooth, the ski lodges and restaurants to distribute them. People would rush over to see if they'd made it into that week's edition, Potter recalled.

Von Moschzisker gave up the gossip sheet in 1977, by which time he'd found another way to make money. He first published a guidebook called the Book of Things to Do, Places to See, and Other Stuff in the Mad River Valley. Von Moschzisker also created "the map" — that is, a hand-drawn map of the valley, surrounded with advertising. It was like something you'd see on a diner placemat.

With a loan from the Farmers Home Administration, von Moschzisker was able to buy a small but sturdy house in East Warren. Dozens of valley denizens availed themselves of that popular home-buying program, even as real estate prices rose.

Von Moschzisker, who later became a sculptor and also published the valley's phone book, recently moved out of his FHA home. He inherited enough money to build another one, not far from where he attended that East Warren wedding nearly 50 years ago.

The view is incredible.

"That's the whole badge of the valley: We're a bunch of people who are not happy living anywhere else, didn't fit in other places," he said. "And this is a misfit place."

The Dedicated Chef

- courtesy of George Schenk

- George Schenk at American Flatbread

When he moved to the valley, George Schenk vowed he'd stay just one winter. He'd recently ended a relationship and thought the Vermont woods would help clear his head. So, in the fall of 1979, he packed up his pickup truck and left Syracuse, N.Y., behind.

"It was the classic situation where I found myself asking, 'What do I want to do?'" said Schenk. "I kept getting the answer 'Vermont,' which was weird, because I was asking a what question and kept getting a where answer. Finally, I decided to go with the answer I was getting."

Unencumbered, Schenk fully embraced the ski-bum lifestyle. He stayed up late and slept in late. He lived for fun. The snow and the economy that winter were suboptimal, but Schenk landed a job taking photos at Sugarbush.

"It was based 100 percent on commission," he said. "I was making 30 bucks a week and starving."

He'd ski and shoot photos during the day, and he eventually picked up an evening dishwashing gig to pay the bills.

"I thought maybe I'd get a meal or maybe get a beer and maybe meet women," he recalled. "All of those things turned out true."

By that spring, Schenk met George Chapel — the woman who'd end up as his wife — while working at Sam Rupert's. To this day, friends still refer to the couple as "boy George" and "girl George."

"George is calm, while his wife is just a pistol of personality," said Peggy Potter, who hired the female George to help her run a wooden bowl decorating business.

Schenk also discovered that he liked cooking and might even have a knack for it. Back then, many area restaurants shut down for the summer, but Schenk's boss offered to make him appetizer cook in the fall.

- Sasha Goldstein

- George Schenk

That summer, Schenk lived with two ski bums. He started a garden and decided to raise a pig. All went well until the refrigerator broke in October. The landlord refused to fix it, and the boys didn't have the cash to make the repair. One roommate bought $20 worth of groceries and left them out on the back stoop to keep cool.

"Sure enough, my pig got into it," Schenk said, laughing at the memory.

He got more serious about cooking and eventually left the ski-mountain work behind. Schenk wound up at the Tucker Hill Lodge, where he learned new techniques and embraced the nascent farm-to-table movement.

"My mother said, 'When are you going to use your biology degree?' I said, 'Food is biological. I am using my degree!'" Schenk recalled.

He cooked his first pizza, which he called a "flatbread," in a stone oven in 1985. By 1987, he'd opened American Flatbread in Waitsfield. He later licensed the name, and more than a dozen flatbread franchises have since popped up around the country. A Boston-area one is scheduled to open this fall, Schenk said.

He and his wife still own and run the original, located on a farm first settled in the 1790s. Schenk recently restored the barn, which is used as a gallery and event space. As of last month, their Lareau Farm property is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Schenk gave Seven Days a tour of the Waitsfield restaurant on a recent winter evening. As tourists and locals streamed in, his wife managed the wait list. The delay gives diners a chance to appreciate the rustic décor, which includes Schenk's Bread and Puppet Theater-style written tablets that are postered on the walls. The writings come from Schenk's "dedications," page-long thoughts, happenings or even philosophical passages that he jots down and adds to the menu each week. Schenk has begun compiling 30 years' worth — about 1,500 — of these dedications into a book.

A fire roared in the enormous cooking hearth as families munched on pizzas featuring local meats and vegetables.

"Part of the phenomenon of the entrepreneurial nature of the people who live here is the phenomenon of necessity," Schenk said. "You've got to make up your own job, and that's a powerful force that in some ways makes it hard to settle in a place like this. But it creates a lot of interesting opportunities. I felt like I had a lot of interesting opportunities to explore who I might be and how I might be and what I might do."

The Innkeeper

- courtesy of Michael Cunningham

- Michael Cunningham, fourth from right

Michael Cunningham never wanted to be a ski bum — he wanted to own an entire mountain.

He and his wife had grown tired of New Jersey, where Cunningham worked a less-than-satisfying 9-to-5 office job. In the late 1960s, they drove up to Barre, where they'd seen a ski area listed for sale in the New York Times. The place was too expensive.

Dispirited, the Cunninghams went to a Marshfield campground for the night. They got to talking about their failed business pursuit with the owners, an elderly couple who mentioned that they owned an inn in Waitsfield.

"They said, 'Well, it's not a ski area, but what about owning a ski lodge?'" Cunningham recalled. "And we said, OK, we'd go take a look."

He and his then-wife, Elaine, bought the Bagatelle in 1969.

The structure, built circa 1825, had been modified to sleep some 103 overnight guests. There were private and semiprivate rooms, but up to 60 could crash — with their own sleeping bags — on pads in a large communal sleeping space. The Cunninghams lived on-site, and Michael had a day job as a ski instructor at Glen Ellen.

Not surprisingly, the inn's "bag space" proved the biggest draw, where $3 a night bought you breakfast and a roof over your head. There were no cooking facilities for guests, but the Cunninghams sometimes provided a first-come, first-served dinner for 20.

Each season, they'd hire at least two ski bums to help out. In exchange for their labor, the workers earned a ski season pass and lodging above the bathrooms in what Cunningham nicknamed "the rat's nest" — an attic crawl space with just one window.

But the deal worked out for both boss and employees.

- Sasha Goldstein

- Michael Cunningham

"They could do whatever they wanted after they finished cleaning," Cunningham remembered. "Usually by 11 they were done, and I didn't have to see them until the next morning. They became part of your family. It was very enjoyable."

The place was packed around Christmas and New Year's, and then again around Presidents' Day in February. Cunningham recalled one Christmas when the Bagatelle ran through its 1,000-gallon holding tank of water. The Warren Volunteer Fire Department had to bring a tanker truck to refill it.

Another year, an overnight guest who'd gotten wasted at Gallagher's Bar & Grill in Waitsfield strolled into the Cunningham's apartment and hopped into bed with the couple.

"I said, 'Who the hell are you?' He had no idea where he was!" Cunningham said. "I dragged him upstairs and stood him in the shower with all his clothes on and turned on the cold water. It's amazing how well that works!"

The Cunninghams sold the Bagatelle in 1977 and later divorced. Michael moved to Granville, just south of Warren, in the late 1980s and has held multiple jobs over the years: He served as Granville town clerk, worked as a project manager in both Warren and Waitsfield, and was the New England sales rep for Mad River Canoe.

The valley itself has changed significantly over the decades — "death, taxes and change, and change is No. 1" — said the 73-year-old Cunningham. But he noted that the core group of original ski bums has stayed pretty much the same.

"We've just gotten older," he said. "Older — not old."

The Southern Belle

- Sasha Goldstein

- Nancy Normandeau

Nancy Normandeau was waiting tables in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., when she made a life-changing decision on a whim.

She doesn't remember the exact year, just that "These two people used to talk about skiing, and it sounded so remarkable that one day I said, 'That's it, I'm moving to Vermont!' and that's where I ended up," Normandeau said. "I actually would have gone to Colorado, but I had very little money and barely made it here."

Normandeau didn't know a soul in the valley but found a room and started job hunting. She lived on bread and peanut butter.

The first night in her new place, a stray cat ate half a loaf of her bread.

"It then had the balls to live with me for about six months!" Normandeau recalled. "My first friend was the cat who ate my bread."

Normandeau's bubbly, infectious laugh and smiling face suggest she's an optimist. After those first few weeks in Vermont, her positivity and perseverance paid off: She landed a waitress job at the Alpen Inn.

She wasn't a natural. A few weeks in, she set a guy on fire. And not just any guy: It was Paul Reutzler, a Sugarbush pioneer who was one of the original instructors at the ski school there.

Normandeau was serving peaches flambé when she dropped the entire tray on him. The brandy ignited with a whoosh, and Reutzler's brand-new suede coat went up in flames.

She pounded out the fire before fleeing the room — and laughed so hard, she started crying, Normandeau said. When she composed herself enough to return to the table, the diners all sympathized, assuming her tears were from embarrassment.

Another fit of laughter emerged, and "I had to fly away," she recalled. "I wet my pants — it was awful. And they left me a huge tip!"

Although young people were all around her, Normandeau said she was lonely at first. Every Sunday night, after the bars closed, there'd be a party, and finally someone — she thinks it was Charlie Brown — invited her to attend.

Once there, she got a weird vibe. People were talking in small groups and looking at her suspiciously. She soon found out why: The pot smokers in the crowd were worried the new girl was a narc. Normandeau quickly assured them that she would happily partake.

"We all smoked a joint, and Charlie said, 'Deep down, you're a really good broad,'" she said.

The "Deep Down" moniker stuck. "I don't think anybody actually knew my name for years," said Normandeau, now 69. She had a southern accent then, the result of growing up in Virginia. Though it's faded away, her nickname persists.

After that night, Normandeau was one of the gang. She'd work weekends at Sugarbush's Wünderbar — where she was forced to wear a dirndl uniform — and at the Alpen Inn. During the week, the ski bums would hit the slopes in "rat packs" — groups of four to 20 people who would bomb down the mountain. Deep Down, who had never previously ventured north of the Mason-Dixon Line, learned to ski to keep up with her friends.

Normandeau worked at numerous local bars and restaurants and claims to have been the first female bartender in the valley. For a long stretch, she worked for Brown at the Blue Tooth, where the 10-cent "dimey" beers, served daily from 5 to 6 p.m., made for some wild evenings. The bar hosted what Brown claims was New England's first-ever wet T-shirt contest — and its legendary "Academy Awards" shows.

In the summers, the crew would hike, play softball and volleyball, and go skinny-dipping in the river, Normandeau said. "We had these great secret spots, until this one guy, who was a flasher, found our one really good spot," she said. "Then we couldn't go anymore."

Normandeau eventually grew up and started her own business. She had a short-lived plant-care company and, in the 1980s, opened the valley's first aerobics studio, named the Body Shop. People would call asking if the place fixed cars, Normandeau said. "I have a problem with names," she added with a laugh.

Normandeau also married and started a family. Her 25-year-old daughter now lives in Jackson Hole, Wyo.

"After four years of St. Lawrence and graduating magna cum laude with honors in two subjects, she's a ski bum," said her mom. "As long as she's happy, I don't care what she does."

Like daughter, like mother. "I've always maintained: I came here as a young woman, and I'm going out in a box," Normandeau said. "I left a couple of times, but I always came back. I think this is where I was meant to be."

The Restaurateur

- courtesy of Mike Ware

- Mike Ware splitting his pants on the slopes

British-born Mike Ware might not have made it into President Donald Trump's America. But the U.S. was a different place in 1959, when a visitor's visa was good from any country and a green card for an English citizen could be obtained in a couple of weeks.

Ware, now 78, stopped off in New York on his way to Australia — and never made it Down Under. He spent several weeks in Manhattan before hearing about an opportunity to the north, in the Mad River Valley.

A friend told Ware of a job opportunity "in Sugarbush, and I said, 'Where's that?' And he said, 'Vermont.' And I said, 'Where's that?'" recalled the restaurateur, who still retains his English accent. "I didn't know you had any skiing over here except out west. That's how I found myself on a Greyhound bus. I arrived in the first week of January 1960 and started waiting tables at Orsini's."

Two-year-old Sugarbush at the time was known as Mascara Mountain, a nod to its fashionable celebrity clientele. Resort owner Damon Gadd recruited Armando Orsini, who ran a popular Manhattan eatery on West 56th Street, to open the restaurant in a retrofitted old barn. It quickly became the glitterati hangout.

"It was synonymous with the image Sugarbush had back then — glamour," Ware said.

In the early days, designer Oleg Cassini was known to visit, as was model Cindy Hollingsworth and Ted Kennedy — then not yet a Massachusetts senator.

"I taught him how to do the twist," Ware said matter-of-factly.

Ware would return to New York City in the summer to work restaurant jobs but came back each fall for the four-month season at Orsini's, where he worked his way up to manager. The place was packed during the high season.

"It was a restaurant and a disco, before they even invented the word 'disco,'" Ware said. "People would make reservations for dinner and not leave so they could stay and dance. It was pretty crazy. We had some wild times."

When he wasn't working, Ware was skiing and partying — every day. There's photographic evidence of him riding a horse into the Alpen Inn late one night in 1962. And although it sounds like a drug-induced hallucination, he also has a vivid memory of horseback jousting with New York restaurateur Vince Sardi outside the Warren Store after the town's famous Fourth of July parade.

"There was a lot of dancing and drinking, a lot of fun," Ware said. "I don't remember drugs, at least with the group I was with. We skied every day, and it seemed to me we never bothered too much about the cold. We didn't wear helmets or hats; we wore headbands. We thought it was so cool — it's unbelievable!"

- Sasha Goldstein

- Mike Ware

As pasta dishes became popular in the late 1960s, Orsini changed the restaurant's name to La Pasta. By 1970, Ware and a friend bought the place. Two years later, they changed the menu and the restaurant's name again — to the Common Man. Ware served veal, steak, chicken, pasta and a fresh fish of the day. The dishes were Italian or Spanish, French or German.

A friend came up with the slogan, "Like dining in Europe without leaving Vermont," and "it stuck beautifully," Ware recalled.

The Common Man quickly earned a reputation as one of the best restaurants in the state, along with Chez Henri, Sam Rupert's, the Phoenix and Tucker Hill Lodge.

"If you wanted to get a good meal in the middle of Vermont, you went to ski resorts. It was one of the first places to get good restaurants," Ware said. "People would drive 30 to 45 minutes for dinner. Now they don't need to, there are so many good restaurants; it's changed completely."

Indeed. No Vermont fine-dining restaurant today would host an annual Waiter's Slalom race, in which restaurant staff donned clunky ski boots and carried a glass of water and a bottle on a tray though an obstacle course of bamboo poles. The Common Man did. "People would hang from the rafters to watch," Ware said, noting that the event got so big, he eventually had to move it outside.

Business boomed in the 1980s, but, in 1987, Ware lost the barn to a fire. Determined to reopen a place with a similar feel, he found the perfect replacement barn in Moretown. He had it moved piece by piece and reassembled it on the site of the old restaurant. When it was complete, few could even tell it was a different building, he said.

Finally, after hosting countless celebrations including weddings and what he believes was the valley's first civil-union ceremony, Ware sold the restaurant in 2004 and retired. That's allowed him to ski more and take up other pursuits, including gardening, fishing and volunteering.

"I'll tell you, there's not enough time in the day," Ware said.

The Craftsman

- courtesy of Jim Henry

- Jim Henry and dog

The valley was plan B for Jim Henry and his then-wife Kay, both scientists. When their jobs at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute fell through unexpectedly, the couple decided to spend the winter of 1969 at the Glen Ellen ski area, where Kay's parents owned a house. Henry taught children to ski on the Mad River Glen bunny hill while Kay worked at the Troll Shop, a ski store in town.

Jim was piloting their Volkswagen van home along German Flats Road on a snowy spring night when the couple saw a horse in the middle of the road.

"That's odd," he remarked to Kay, who was riding shotgun.

Instead of running away as their vehicle approached it, the horse charged. Its knee came through the window, striking Kay in the face, while its head collapsed the roof. While the horse got away, the blow had broken Kay's jaw. The couple got a ride to the hospital in Burlington, where she spent days recuperating. Their van was badly damaged, and the Henrys found themselves stuck in Waitsfield.

"We came for the skiing but stayed because a horse jumped into our car," Jim Henry recalled with a laugh.

Now 76, he never considered himself to be a true ski bum. But, along with his teaching gig, Henry would take racing photos each weekend at Glen Ellen for the ski area's owner, Walt Elliott. Henry would run home and develop some 160 photos each weekend in a downstairs bathroom-cum-darkroom.

"If Walt could read the racer's bib number and 'Glen Ellen,' I'd get a buck. Then he'd send them to the newspapers," Henry recalled. "It would say 'Glen Ellen,' so it was free advertising. All it cost Walt was a buck and a stamp to mail it. So, that's how we learned marketing."

The couple had purchased land to build a ski house, but they eventually decided to make it their full-time residence. Henry and his wife let ski patrollers from nearby mountains live with them in exchange for doing work on the house.

At around this time, Henry, a national champion white-water canoeist, began building his own boats. He used the marketing experience he had learned from Elliott to build his brand, Mad River Canoe, into an international enterprise. At its peak, he and Kay employed some 80 people out of their Waitsfield headquarters. In 1987, the couple divorced and Henry sold his share to Kay.

- Sasha Goldstein

- Jim Henry with a canoe

He went on to start another wildly successful business building bird decoys. Henry dubbed the enterprise Mad River Decoy and sold the facsimile animals to conservationists, who used them to help move or preserve a species. Henry has since given the business to the Audubon Society, which has used his decoys to successfully restore colonial seabirds.

Henry, who still lives in Waitsfield next to his original workshop, trademarked his name and gets royalties from sales of canoes built using his original designs. After having both knees replaced, he's no longer downhill skiing. But he's plenty busy. He still builds beautiful handmade canoes in the shop, a simple two-story structure in the woods.

On a recent Thursday, Henry was hard at work creating a bird decoy mold. He's filming the process so Audubon Society employees can start doing the work themselves.

He said with a chuckle, "I keep retiring, and it doesn't work."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.