- Rick Veitch

Deep in the green wilds of southern Vermont, the state's cartoonist laureate held court outside his West Townshend art studio as the afternoon sun beat down. Rick Veitch, a tall, soft-spoken man of 71, stood staring toward his house and the nearby pond, both adorned with wildflowers and other plantings cultivated by his wife, Cindy. Perhaps feeling a touch of nostalgia after speaking about his life and career for hours, Rick veered into the present with a grin.

"I count my blessings," he said. "I'm just about the luckiest guy you'll ever meet. How many people get to do what they dreamed of as a kid?"

What Rick dreamed of as a kid was being an artist, and a cartoonist in particular. Over his half-century career, he has more than succeeded, leaving an indelible mark on comic books as a medium. He started out in the underground comics of San Francisco in the 1970s, graduated with the first class of the famous Joe Kubert School of Cartoon and Graphic Art in New Jersey, and worked with Alan Moore on DC Comics' Saga of the Swamp Thing, a series that he later wrote and illustrated solo.

In April 2020, Rick became Vermont's fourth cartoonist laureate, receiving congratulations from Gov. Phil Scott in a virtual ceremony. At the time, James Sturm of the Center for Cartoon Studies in White River Junction, which founded the honorary three-year laureate position, explained in an email to Seven Days that Rick was selected for his "singular career that includes groundbreaking genre work for the big superhero companies, his own creator-owned graphic novels, educational comics, and explorations into the subconscious...

"Rick's imagination is commensurate with his stunning craftsmanship," Sturm concluded.

- Courtesy Of Rick Veitch

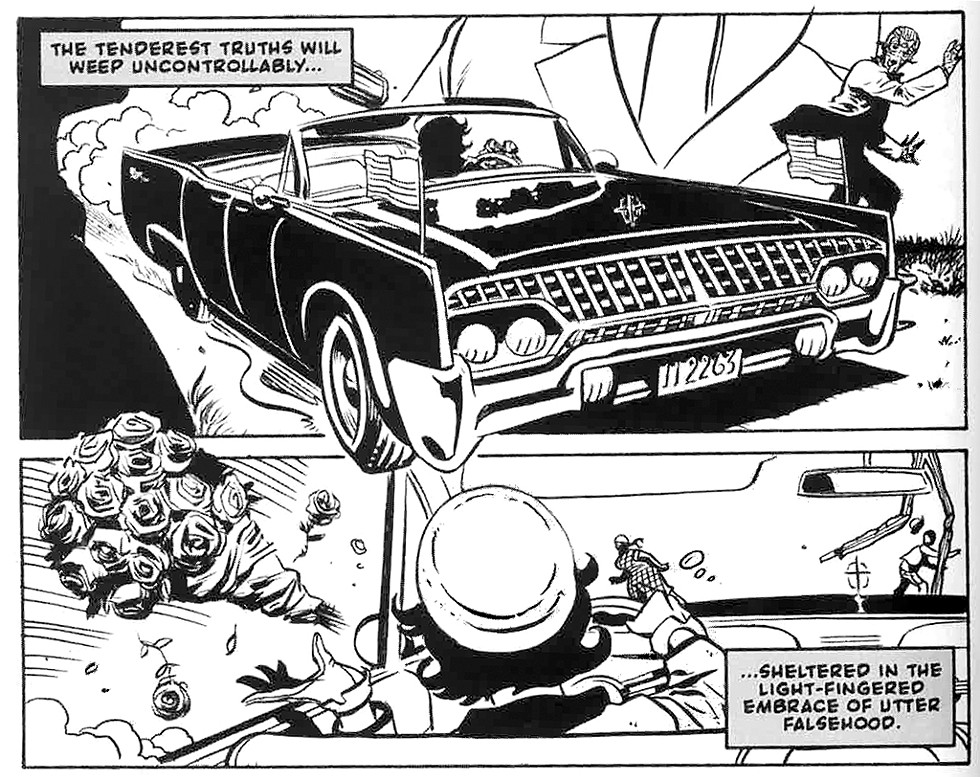

- Excerpt from Can't Get No, by Rick Veitch

While Rick may call himself lucky, he had to work and "fight like hell" to get where he is, according to fellow artist and Vermonter Stephen R. Bissette, who wrote a 2011 book about his old friend called Teen Angels & New Mutants.

Before Rick went to art school, Bissette recalled, "he was fighting every day of his life to make an art career happen. His parents weren't supportive; his teachers weren't; really only Tom was."

Tom Veitch was Rick's older brother, an industry legend in his own right who penned underground comics in the '60s and '70s and went on to write massively successful Star Wars comics. The two brothers would inspire and confound each other over the course of their long careers, introducing countercultural beliefs and underground sensibilities to mainstream comics.

Told for most of his life that comics weren't a serious pursuit, Rick spent decades working to legitimize and evolve the art form. He fought the odds to survive in a volatile industry and brought the underground and the mainstream together with his work on books such as Swamp Thing.

And he seems to have succeeded. Today, comic book characters dominate pop culture, their names known far beyond the ranks of so-called "nerds." Though comics may come in new formats these days, their sales have skyrocketed, and not only among young people. In the first half of 2021, Publishers Weekly reported, graphic novels comprised a whopping 20 percent of adult fiction unit sales.

Comics have never been more mainstream. So why is Rick an outsider again? And, more importantly, why is he happy about it?

"God, I wish I had this situation when I was first starting," Rick said as he surveyed the rolling emerald hills. "But you need to work toward something like this."

In his peaceful studio in the woods, he's a thriving comics artist with no boss or publisher to report to. It took him a long, winding journey to get there.

Industrial Blues

- Courtesy Of Gary Spaulding

- Rick Veitch, 1979

Rick's earliest home was Walpole, N.H., but he's quick to point out that he was born on the Vermont side of the Connecticut River in the Bellows Falls hospital. In 1951, he came into a family brimming with creativity. His father was a Scottish immigrant who grew up in Queens, N.Y., and studied commercial art at Columbia University; his mother was a talented actress. The family moved across the river to Bellows Falls when Rick was 5, and soon there were six Veitch kids: five brothers and one sister.

"We were spread out in age. Tom was 10 years older than me," Rick said. "But for a time, we were all packed into that old house, and the energy level was just crazy."

Rick recalls an idyllic town overflowing with elm trees and kids who had their run of the streets. But the town's industries — notably the paper mills — were dying, making the Bellows Falls economy unforgiving to young, job-seeking men.

In Rick's recollection, the town was also inhospitable to a budding artist. To the generation that had grown up in the Great Depression, creative work just didn't look like a way to put food on the table.

"I knew in my heart, from the time I was really small, that I wanted to be a cartoonist," he said. "I still remember teaching myself to draw and how to even hold the pencil when I was 5."

Rick loved graphics and logos, and he collected signs. But it was his discovery of superhero comics in the '60s that set his imagination on fire. Inspired by a growing love for artist Jack Kirby (cocreator of Captain America, the X-Men and the Fantastic Four) and Spider-Man cocreator Steve Ditko, Rick dived headlong into the medium, much to his parents' chagrin.

"Nobody really thought I should do it," he said.

Bellows Falls did have one resident artistic success story, the painter Stephan Belaski. "He had painted these incredible murals at the schools, and he studied at the Sorbonne," Rick recalled.

So one day, Rick knocked on Belaski's door and informed the painter that he, too, wanted to be an artist, asking Belaski for advice on how to proceed.

"He just said, 'Don't do it, kid,'" Rick recounted. "He tried to talk me out of it, like everybody else."

No one was more opposed to Rick's desire to become an artist than his parents, despite their own creative tendencies.

Though Rick's dad had come to Bellows Falls to work for Robertson Paper, he supplemented his income by doing commercial art projects on the weekend. "He would set up his table to work on the art," Rick recalled, "and I'd grab my stuff and set up next to him to draw, but he just never responded. He didn't want to show me anything, either."

When Rick reached seventh grade, his grades dropped, and both school officials and his parents seemed to think his art was the problem. One day, Rick came home from school to find that his parents had thrown out not only the comics he'd bought but the ones he had made himself, determined to scuttle his career before it began.

That very same week, Rick received a package from Ed "Big Daddy" Roth, a California-based cartoonist whose "Draw a Monster" contest he had entered. He had won an honorable mention.

"And there was my name in the magazine," he said with a still-satisfied grin, more than 50 years later, referring to DRAG Cartoons, where the contest appeared. "That's when I knew. They couldn't stop me then."

Blood Brothers

- Courtesy Of Rick Veitch

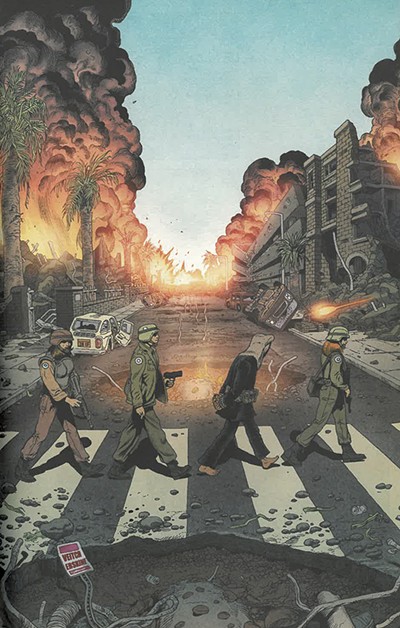

- Excerpt from Army @ Love, by Rick Veitchand Gary Erskine

Around the Veitch household, Tom was everybody's favorite. Smart, driven and massively cool in the eyes of his younger siblings, he set the pace.

"He was a really industrious kid, too," Rick said of his brother. "He built his own amplifier for his record player and eventually wired our whole house for sound so he and his friends could be DJs and spin records for us all day."

At one point, Tom built his own radio transmitter, which he used to broadcast to the town until the Federal Communications Commission found out and shut him down.

"That's the kind of kid he was," Rick said. "He was artistic, but he had a good engineering head and wasn't afraid to take on a complex problem. He was also one of the few people in my life who understood the worth of art."

Rick's brother Michael, five years his junior, recalled envying the attention Tom showered on Rick when they were kids. "We all wanted Tom's attention — he was the cool older brother, y'know?" he said. "So we were a little competitive about it back then.

"Tom exposed me to a lot of music and art," Michael said by phone from his home in Woodstock, N.Y. The fifth Veitch sibling is a lifelong folk musician who has worked with Shawn Colvin and written songs for Judy Collins. Much like Rick with his art, Michael felt encouraged by Tom, who wanted to inspire his younger brothers.

After a trip to San Francisco, Tom "brought me back the first Grateful Dead record," Michael remembered. "No one had even heard of them yet!"

In 1964, like his father before him, Tom matriculated at Columbia University in New York City. That's when things started to go awry between Tom and his parents, according to Rick.

"Tom became really rebellious when he got to Columbia. He got into acid and met all these Lower East Side poets," Rick said. "And it was right around then that our family started to unravel quite a bit. So I grew up without much direction after that, because my parents were sort of spiraling down." His father would die in 1970.

Tom was soon off to the West Coast again. Before he went, he and Rick created their first underground comic, Crazy Mouse. The University of Vermont's student paper, the Vermont Cynic, published it in 1968, and it can still be found in the archives.

It was Rick's first proper published comic. He didn't wait long to drive cross-country to visit Tom, who'd made connections in San Francisco. Working with artist Greg Irons, he was producing edgy underground comics such as The Legion of Charlies and Deviant Slice Funnies.

Freshly arrived at Tom's place in Stinson Beach in 1970, Rick drew an eight-page sequence of an ax murder — perfect for the publishers of Last Gasp, the underground outfit with which Tom was working. Tom showed the comic to Last Gasp, which hired Rick. The brothers set about collaborating on their first published comic book, Two-Fisted Zombies, and Rick returned to Vermont ready to draw. Married by then with a son, Ezra, he had a little cabin in Grafton, peace and quiet, and, finally, a professional artist gig.

Unfortunately, the U.S. Supreme Court had something to say about that. In the landmark 1973 case of Miller v. California, the court redefined pornography, leaving it up to local authorities to decide what was indecent. The ruling destroyed the underground comics movement in one blow because its sales depended on a network of head shops, sex shops and sex book distributors that were suddenly subject to potential prosecution.

- Courtesy Of Rick Veitch

- Excerpt from Army @ Love, by Rick Veitch and Gary Erskine

With the underground work drying up, Rick took a job at a local wood and stone shop in 1974 but was summarily laid off. He sent a portfolio to Marvel Comics, hoping to make the move to more mainstream comics fare. Though the company's art director saw potential in Rick's work, he felt Rick needed training.

After a tiny ad in the New York Times announcing the launch of the Kubert School "leapt out" at him, Rick immediately drove to Dover, N.J., to see it and meet renowned comics artist Joe Kubert. When he showed Kubert Two-Fisted Zombies, the DC Comics veteran accepted Rick into the school on the spot.

"The only problem was, I was completely fucking broke," Rick said, laughing as he thought back to those lean days. "But Joe's wife, Muriel — who was just an amazing woman — told me about this government program called CETA that I might be able to qualify for."

The Comprehensive Employment Training Act was a federal program designed to help low-income students attend trade schools. Rick knew it was a long shot to get the loan applied to tuition at a cartoon school, but he kept calling until he got the answer he wanted.

"I must have called everyone in that chain," he said. "Finally, I reached this lady who told me that she was looking at my art with all these supermen in it, but she didn't see any superwomen in there. Fortunately, I had my wits about me enough to say, 'Well, that's what I need to learn!'"

The loan secured, Rick left for New Jersey in 1976 with $20 in his pocket, a box full of groceries and a bike. He and his first wife would divorce that same year. In New Jersey, he would meet Cindy.

The future beckoned.

Avengers Assemble

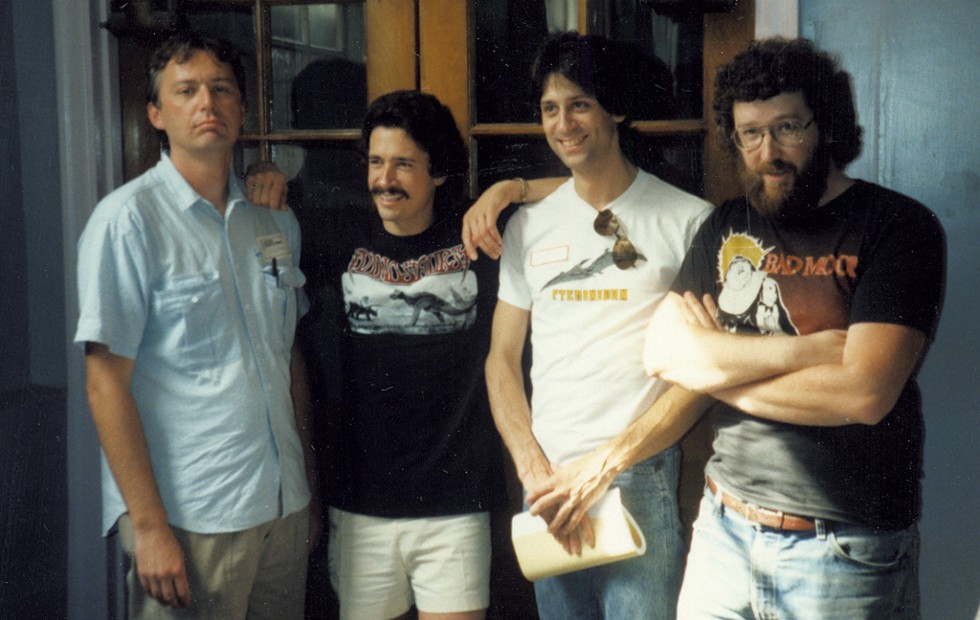

- Courtesy

- From left: Rick Veitch, Thomas Yeates, John Totleben and Stephen R. Bissette in 1986

"Rick is an artistic chameleon," Bissette said by phone as he tried to describe what makes Rick's art so potent. "He can be edgy or slick; he can be underground or polished."

"He has such a clarity to his style; the way Rick tells a story in a panel is really just incredible," said Thomas Yeates, another graduate of the Kubert School's inaugural class who went on to leave his mark on comics, working on Tarzan, Swamp Thing and his current gig, the weekly Prince Valiant comic strip. "He impressed me from the start, right when we all got there."

Yeates and Bissette, along with another future Swamp Thing artist, John Totleben, met Rick in their early days at the Kubert School, where the four would form a strong professional and personal bond. The experience left a mark on them all. Whenever he's outside on a warm September day, Rick still flashes back to arriving in Dover in the summer of 1976 and meeting his friends.

"I met Bissette and Totleben and Yeates almost immediately," Rick recalled. "We all had different things we were passionate about, but there was so much overlapping of influence and so much stuff we loved in common. I made friendships there in that first year that have lasted my whole life."

The four were determined to infiltrate a rapidly dying industry to help it adapt to changing times. While censorship threatened underground comics, mainstream comics had an aging fan base and a dearth of outlets. The era of comic book shops and conventions hadn't yet dawned.

"When we graduated from Kubert, we thought we were fucked," Bissette said. "The old business model for the comic industry had imploded; the distribution had gone bad. Not for the last time, by the way!"

Bissette remembers teachers at Kubert telling students that the industry they were trying so hard to enter was all but doomed. He, Rick and their friends weren't buying it.

"I kept using the metaphor back then that we'd be the primitive mammals," Bissette said, "and we'd just start eating the dinosaur eggs and find our survival niche."

That opportunity arrived for Bissette and Rick not long after they graduated from the Kubert School. Artist Alex Toth had been hired to create a comic book adaptation of Steven Spielberg's World War II comedy 1941 for Heavy Metal magazine. When he dropped out at the last minute, the magazine hired the two Vermont artists.

With only two months to write, draw, ink and color a 48-page comic, and with only an early, barely recognizable version of the script to work from, Rick and Bissette drew on their underground roots and made a comic with very little resemblance to the film. Full of gore and schlock, the adaptation shocked even a displeased Spielberg, who wrote Heavy Metal editor Julie Simmons a perturbed letter in 1979.

"I have had a chance to further examine the '1941' HEAVY METAL BOOK and have found many aspects of the book disturbing," the director wrote in a letter still visible on Heavy Metal's website. "On the sweeter side, we take our hats off to your two artists. We all seem to agree on one thing, they are ruthlessly talented (though demented)."

Though the film flopped, the comic spurred on Rick and Bissette, who found more work at Heavy Metal and eventually at Marvel's answer to Heavy Metal: Epic. Soon, all four of the friends had regular, paid work. Totleben and Bissette connected with British writer Alan Moore, famous for seminal works such as Watchmen, Miracleman and V for Vendetta. They followed Yeates after his run on Swamp Thing and, along with Moore, turned it into one of the best series of its day, full of dark fantasy, big ideas and incredible art.

- Courtesy

- From left: Rick Veitch, Stephen R. Bissette and John Totleben in 2019

Rick took over the art for Swamp Thing with issue No. 50 in 1986 while working with Moore on Miracleman.

"Alan was just like us, only more brilliant," Rick said of working with Moore. "Same underground sensibilities but also the same desire to work within the mainstream and change it. There were times I didn't even understand his scripts until I drew them!"

Rick's faith in his art's capacity to create bridges of meaning has always pushed him into new territories. In Swamp Thing No. 56, for instance, "My Blue Heaven," the hero finds himself in another world with "aquarium light filtering through clouds of bleached cobalt," reads Moore's text for the comic.

Rick unleashed his inner Jungian and rendered a cerulean world surrounding the displaced hero. Silhouetted against a field of stars, Swamp Thing stands on a beach, looking down at a pool of water from which columns of steam rise. As he picks up a massive beetle from the shore, the cobalt clouds Moore described seem to surround him, mingling with twisted and mangled trees like something out of a dream.

On the next page, there's a splash panel of Swamp Thing's fern-encrusted, now-blue hands clutching the wet beetle. In a watery reflection on the beetle's exoskeleton, Swamp Thing sees his own face staring back at him. It's a clever display of visual poetry, a perfect adaptation of Moore's words and one of many examples of Rick's capacity to let his unconscious flow through his pencil.

In 1987, Moore left Swamp Thing and handpicked Rick to take over as writer, a daunting challenge.

"Alan and I used to joke that I was committing career suicide," Rick said with a laugh. "But we both knew I was the right guy to do it. Alan wanted it, my editor ... wanted it, and I was looking for a steady paycheck to pay off my mortgage."

After he turned in his first two issues and didn't receive a paycheck, he contacted DC Comics. He was told that because he was writing and drawing for the company, he could no longer be paid as a freelancer. He would have to become an employee of Time Warner, DC Comics' parent corporation. But all that paperwork took time to process, so, in the meantime, the company offered Rick a loan to help him pay his bills.

The catch was that the loan came attached to a contract. To get the loan to cover the pay they hadn't given him, DC Comics required that Rick sign with them exclusively — a bad sign of things to come, he said.

The following year, Swamp Thing No. 88 would be the last straw between Rick and the company. He wrote an issue in which the titular character is thrust back through time, eventually meeting Jesus Christ.

DC Comics had recently implemented a new, more stringent content policy, and Moore, Bissette and Frank Miller (Batman: Year One) had quit in protest.

Rick claimed that then-DC Comics president Jenette Kahn told him he didn't have to worry about the company's list of dos and don'ts; as long as he worked with his editors, they'd get it done. He pitched the Swamp Thing-meets-Jesus issue, and it got the green light. But after an apparent change of heart, Kahn canceled the issue.

"We believed that the story concept would be offensive to many of our readers," she told Time magazine in 1989.

"The issue was already penciled, and it was just waiting for inks when they pulled the plug," Rick said. "My position at the company became untenable because all these people sort of blamed me, like I hoodwinked them or something. When, in reality, they all knew exactly what I was doing."

Rick quit, vowing never to work for DC Comics again.

The Will Eisner Effect

- Zach Stephens

- Rick Veitch working on a new story about Philip K. Dick

"Pop culture can be unforgiving," Bissette pointed out. "Guys like Rick and I worked so hard to get inside that beast and change it. And now, years later, we're seeing some of that work get thrown back at us in very interesting ways."

He and Rick have thought and talked often about how their work has affected pop culture. Considering the stranglehold comic book films currently have on Hollywood, the artists' impact appears substantial.

But Rick's work may have become even more influential since he left DC Comics and started working on his own projects.

After leaving the company, "I met [Kevin] Eastman and [Peter] Laird and saw what they were doing with their book," Rick said, referring to the underground-to-worldwide smash Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, which he would eventually work on. In 1990, that series inspired him to create his own imprint, King Hell Press, on which he released some of his best work, including The Maximortal (1992), a twisted retelling of Superman's origin, and Brat Pack (1990), a satirical look at superhero sidekicks.

"Brat Pack is a clear and obvious precursor to The Boys," Bissette claimed, referring to the 2006 DC Comics title that spawned an ongoing streaming series. "But The Boys gets the gravy train. And that's just the way pop culture works; there's no point in getting mad about it. I mean, look at the [Oscar-winning] Guillermo del Toro film The Shape of Water! It's the best Swamp Thing movie there's ever going to be."

These days, Rick doesn't waste time wondering how much of his influence is detectable in the latest deluge of superhero celluloid. His track record gave him clout as an indie publisher, but as the new millennium dawned, the distribution system for indie comics again began to fray. Rick needed new sources of income.

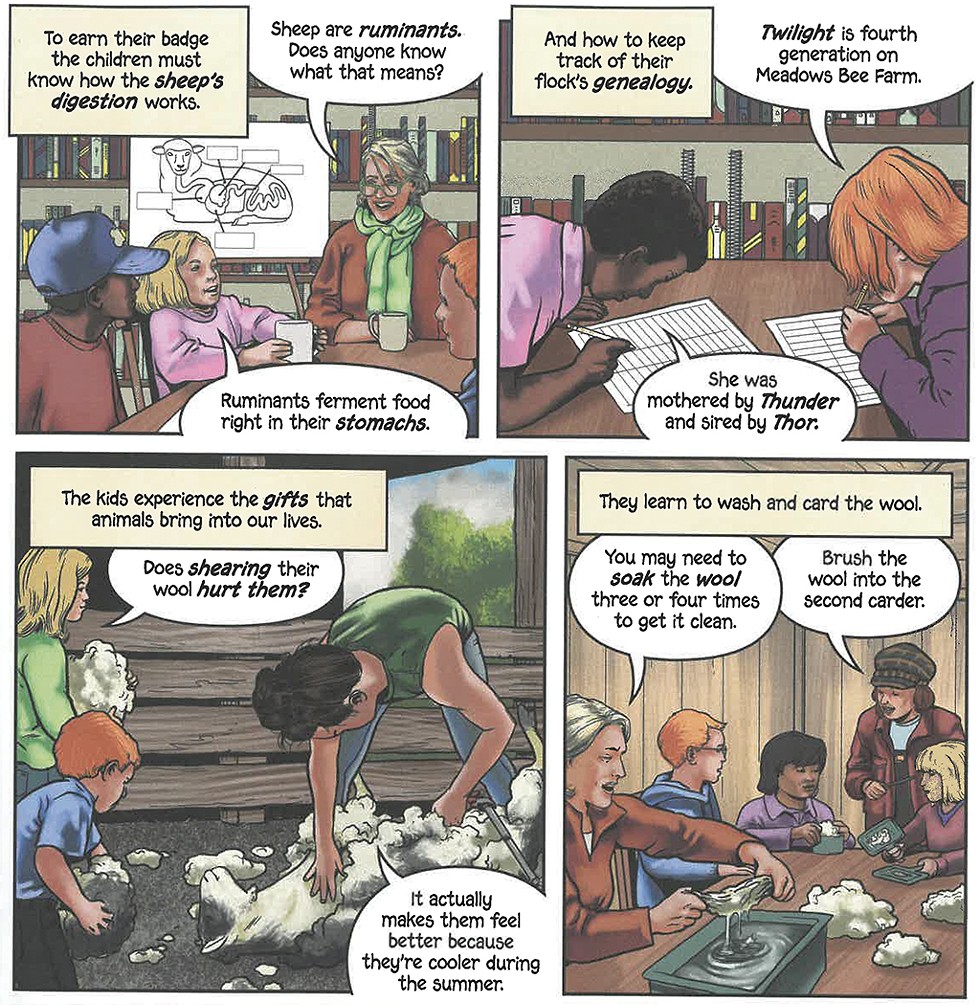

In 2016, he embarked on a new phase of his career when he founded Eureka Comics with fellow artist Steve Conley. The company creates educational comics, using art to teach students everything from basic math to the story of Crispus Attucks, reportedly the first colonist killed in the American Revolution.

The inspiration for that venture came decades earlier, when Rick heard pioneering comics writer Will Eisner speak at the Kubert School. Eisner, who popularized the phrase "graphic novel" in the 1970s, spoke to the young artists about working on educational and informational comics, which he considered an underutilized market.

"That talk really stuck with me, but I didn't have a chance to actualize on it until about 10 years ago," Rick said. That's when the University of Québec reached out to Rick about creating educational comics — on the advice of Bissette, who had turned down the offer.

"I enjoy doing the educational comics; they're a real challenge," Rick said. "Even better, they pay a lot more than regular comics. If I do a few of them, I can fill the economic meter up enough to work on my other stuff."

- Courtesy Of Rick Veitch

- Revisioning Food, Farm, and Forest: The Badges of Meadows Bee by Rick Veitch, Steve Conley and Kirby Veitch

His latest book with Eureka is the forthcoming Who Farms?, a group venture of UVM's Humanities Center and Center for Sustainable Agriculture, the Vermont Folklife Center, and the Vermont Historical Society, funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The graphic novel tells the story of five different Vermont farm families and the struggles they face.

Cheryl Herrick, communications and project support specialist at the Center for Sustainable Agriculture, said the participating organizations initially worried that the national endowment wouldn't consider a comic book a valid teaching tool.

"So we did some research," Herrick said, "and uncovered the fact that people tend to use more of their brain when looking at images combined with words. And there's really just something incredible about honoring somebody's experience by drawing them in their lives, showing what their lives are like — which Rick and Steve [Conley] did, and it was so powerful."

Luis Vivanco, a UVM anthropology professor and codirector of the Humanities Center, was already a fan of Rick's before they started the Who Farms? collaboration.

"Rick never presented himself as some kind of luminary of the comics world, which he totally could have," Vivanco asserted. "Instead, he comes off as this humble collaborator who really wants to tell an interesting story."

Working on educational comics had another positive effect on Rick's life: It was a chance to collaborate with his eldest son, Ezra — who, like his younger son, Kirby, is an artist. While Kirby does watercolors and digital painting, Ezra has moved into a career in comics.

"About six years ago, Dad asked me to help him out with the Eureka stuff," Ezra said by phone. "For a while, I just couldn't do the artist thing. It was honestly kind of heavy having your dad be Rick Veitch and trying to pursue that avenue."

But eventually, Ezra caught the comics bug. After working on some Eureka comics, he began creating his own fantasy series called The Chronicles of Templar, and he worked on the 2021 local compilation The Most Costly Journey: Stories of Migrant Farmworkers in Vermont, Drawn by New England Cartoonists.

"It's really cool to watch Ezra evolve as an artist," Rick said. "He's really been doing some exciting things and learning to work with panels in this neat way."

Now, Ezra and Rick talk about collaborating on stories, something that both excites Ezra and gives him a sense of things coming full circle.

"Dad was making his first comics with his brothers Tom and Michael when he was just a kid," Ezra pointed out. "And now he's working on comics with his own kid. There's some really cool symmetry to that."

Full Circle

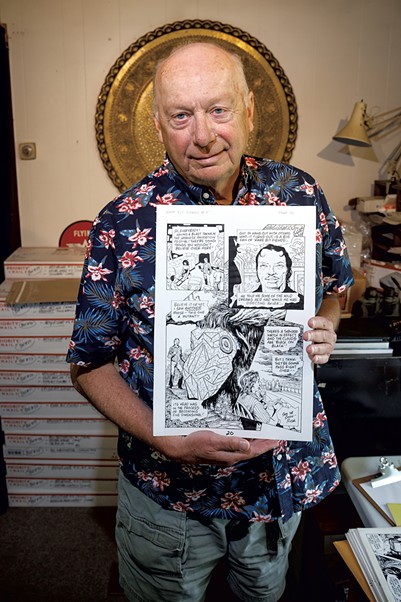

- Zach Stephens

- Rick Veitch holding a piece of art from Roarin' Rick's Rare Bit Fiends in his studio

Tom Veitch died at 81 on February 14 of this year. Rick doesn't like to delve into the details, but he and his older brother and mentor had been estranged for years leading up to the elder Veitch's death.

"I had sort of helped Tom get back into the comics business in the '80s," Rick said. "But our relationship never really came back when we were older. Especially after 9/11, he got really into Fox News, and you know ... well, I'm a Bernie bro, so we fought like cats and dogs for a long time."

"I couldn't really talk politics with Tom," Michael admitted. "But we were close on other levels. I spent a lot of time talking with him the last three years of his life, so I feel pretty good about where we're at. He promised me that he'd come visit me after he died, but he hasn't popped up yet."

Bissette, who knew and worked with Tom, said the older Veitch had influenced Rick in many ways.

"When I met Rick at Kubert, we were in a situation that was super supportive of our creative endeavors," Bissette said. "But before that, Tom was the only one who ever did that for Rick, and that will never change."

"I think Tom also showed Rick the things he didn't want to do," he continued. "There was a lot of rivalry and power struggles, which is, honestly, inevitable with siblings. Rick didn't have any of that shit with me and Yeates and Totleben. We were all egoless and having fun creating, which I think freed Rick from the struggles he had when he tried to create with Tom as they got older."

Back in his studio, Rick pulled out the graphic novel he released in June called BONG! Comix: Underground Classix. It's a collection of his most underground work with creators such as Harvey Pekar, Bill Kelley and Bissette. Two-Fisted Zombies is in the compilation, and there's no denying Rick's happiness as he looks at the comic he and his brother made 54 years ago.

"Once he knew he was ill and there wasn't much time left, Tom reached out to me, and we started meeting again," Rick said as he gingerly set down the comic beside a drafting table he's had since the Kubert School. "We both said, 'No more politics,' and we were able to reconnect in a really meaningful way, which I'm incredibly grateful for."

Though the brother who helped him become a professional and autonomous artist is gone, Rick takes comfort in the fact that he's doing what he always wanted to do, on his own terms. His output remains prodigious. Besides the Eureka books, it includes collections of his dream comics (illustrations of his own dreams, which he faithfully writes down every morning after walking) and new issues of Roarin' Rick's Rare Bit Fiends and Maximortal.

At 71, Rick seems unlikely to slow down anytime soon.

"My back feels good; my wrist is good. I had cataract surgery a few years back, so my eyes are good," he said, listing off the typical artist's ailments.

He smiled widely, a hint of mischief in his eyes.

"They'll be taking the pencil from my cold, dead hands," he said.

The First Veitch

- Courtesy

- Tom Veitch

Though Tom Veitch helped inspire his brother Rick to go into comics, he himself was a poet before all else, according to his friend and fellow Vermont comic creator Stephen R. Bissette. Tom's first published work, Literary Days, was a poetry collection he composed in 1964 while attending Columbia University. During those years, he was part of the Poetry Project at St. Mark's Church, a hub for the Lower East Side poetry scene, and he penned collections such as My Father's Golden Eye and Death College.

Spiritual searching was another through line of Tom's life. In 1965, he left New York City for the silent halls of the Weston Priory in southern Vermont, where he lived as a cloistered Benedictine monk for three years.

Tom moved out west in 1968, met his future wife, Martha, and founded his own poetry magazine, Tom Veitch Magazine. In San Francisco, he met and began collaborating with underground comics artist Greg Irons. The two produced comics such as Slow Death, Skull Comix and Deviant Slice Funnies, which showcased Tom's dark humor and crisp, clever writing.

Those comics, along with Two-Fisted Zombies, Tom's collaboration with his brother Rick, helped inspire Bissette to make comics himself. It was only later in life that Bissette would discover the depth of Veitch's writing, particularly his poetry.

"Once I went and read a lot of that stuff, Tom's writing really came into focus for me," Bissette said. "A lot of his work, just like Rick's, was all about transformation."

After the collapse of underground comics in 1973, Tom continued publishing his poetry, winning Big Table Publishing's Poetry Award that same year. He wouldn't return to comics until he partnered with artist Cam Kennedy for a six-issue limited series for Epic Comics called The Light and Darkness War.

Tom sent this tale of a disabled Vietnam vet in a coma, dreaming of an interstellar war, to George Lucas. The Star Wars creator promptly hired him to write a sequel to the massively popular films for Dark Horse Comics. Again with Kennedy, Tom put out Star Wars: Dark Empire in 1991, followed by the popular Star Wars: Tales of the Jedi series in 1994 and Dark Empire 2 in 1995.

Tom had a long and successful career in comics, working on his own creations such as The Nazz, and writing superhero books such as DC Comics' Animal Man. The last work he published before his death in 2022 was a spiritual memoir called The Visions of Elias: A True Story of Life in the Spirit.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.