- Courtesy of Zack Porter

- Camel's Hump

An environmental group is following through on its threat to sue the state to block the logging of thousands of acres of mature forest in Camel's Hump State Forest.

Standing Trees, a Montpelier-based anti-logging group, filed the suit late Wednesday in Vermont Superior Court.

“Public forests are among our greatest bulwarks against climate change and extinction, but they’re being sold to the highest bidder while the public is kept in the dark about how decisions are made,” Zack Porter, executive director of Standing Trees, said in a press release. “If successful, this lawsuit will put the public back in control of public lands.”

The group has called for a moratorium on logging in state parks and forests and in the federal Green Mountain National Forest. It argues that the benefits of leaving maturing forests intact — such as carbon sequestration, clean water, wildlife habitat and flood resilience — far outweigh the economic benefit to the state of allowing logging on public lands.

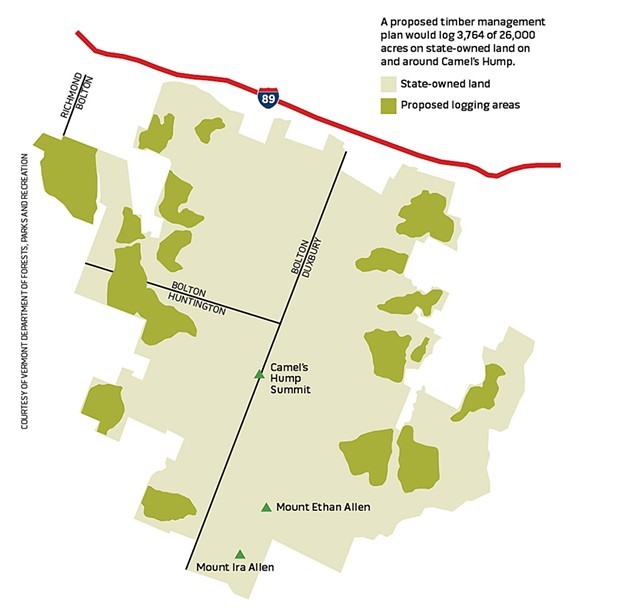

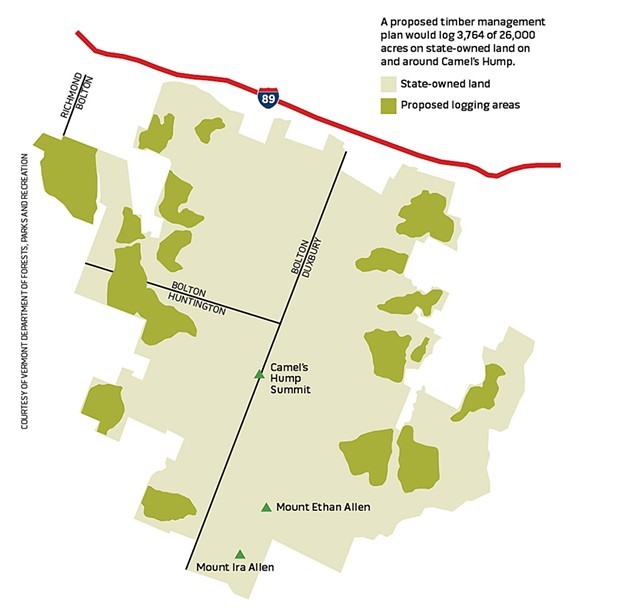

Standing Trees claims the state Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation relied on outdated science when drafting a plan for logging 3,800 acres of forest around Camel's Hump over the next 15 years. That’s about triple the rate of harvesting in the forest done over the past 25 years.

The group argues that the state has failed to adopt required rules for conducting logging on state lands, essentially allowing state foresters to divvy up chunks of state land for logging as they see fit.

The management plan for Camel's Hump, which includes 34 different areas of logging, did go through a public review process. But the group argues that the department follows internal “written procedures” when crafting logging plans that “have never been subject to public comment, public hearing, environmental impact review, consideration of alternatives legislative oversight or judicial review.”

The suit was filed by Bristol attorney James Dumont. Additional plaintiffs are Duxbury residents Jamison Ervin and Alan Pierce, who live on property that abuts Camel’s Hump State Park.

The suit argues that the department was required to go through a public rulemaking process for logging on state lands because it was petitioned to do so by more than 25 people. But the department declined, according to the suit.

The group has also argued that the department ignored a 2015 study that showed logging on state lands needed to be done far more carefully to reduce the risk of flooding due to increasingly intense rainfall driven by climate change.

That claim has "zero merit," Mike Snyder, commissioner of the Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation, said last month.

Snyder could not be reached on Wednesday for comment on the suit. But he has previously accused the group of statutory “cherry picking” and of misstating the department’s planning processes.

The group is essentially reading one section of state law that seems to suggest formal rules are required for timber harvests, while ignoring numerous other areas of law that give Snyder the clear right to manage forests for timber sales, he said.

This includes specific language in the law requiring that what is formally known as the Camel’s Hump Forest Reserve be managed for “sustained production of timber, water conservation, wildlife management, hunting, hiking, cross-country skiing, and nature appreciation.”

“Any productive conversation regarding use of State lands should acknowledge the clear directives and statements of policy by the General Assembly recognizing the importance of timber harvesting for maintaining Vermont’s forests,” Snyder wrote to the group in July in response to its demands to halt the timber sales.

“Any productive conversation regarding use of State lands should acknowledge the clear directives and statements of policy by the General Assembly recognizing the importance of timber harvesting for maintaining Vermont’s forests,” Snyder wrote to the group in July in response to its demands to halt the timber sales.

The first of those sales was scheduled to begin this year, but Snyder said for all practical purposes the sales aren’t likely to be conducted until next year; any logging won’t happen until next winter.

Such timber sales not only generate revenue for the state but provide raw, local material for the state’s forest products industry and improve forest health by creating a diversity of tree ages. Clear-cuts quickly regenerate to create ground cover and habitat for a variety of species, foresters argue.

About 78 percent of the state is forested, one of the highest percentages in the nation. About 20 percent is publicly owned, with 80 percent privately owned. The conversion of private forestland to residential parcels or other uses poses a far greater risk to forests than active logging, Synder has said.

Opponents nevertheless argue that climate change requires an urgent shift in the way the state manages public forestlands.

Over the summer, Porter of Standing Trees vowed to “up the ante and play hardball” to protect state forests to help fight climate change. Earlier this month, the group held a protest outside the Rochester ranger station of the 400,000 acre Green Mountain National Forest. More than 100 activists gathered to condemn a plan to log an area called Telephone Gap around the town of Chittenden.

They held up banners that read "Stop the Destruction" and hiked up to a nearby section of clear-cut forest and lay down in a field of gray stumps beside banners that read “Climate Emergency: Do Not Log” and “No Clearcuts in VTs National Forest.”

The group argues that the forest service logging plans violate the spirit, if not the letter, of President Joe Biden’s executive order earlier this year requiring the service to categorize and monitor old-growth trees on federal lands and to implement “climate-smart management and conservation strategies.”

The majority of the logging slated for the 32,000-acre Telephone Gap area would be trees that are 60 to 119 years old, which Porter said clearly makes them in urgent need of protection.

The group followed up its demand for a halt to the Camel’s Hump logging plan with a public records request that identified a 2015 report aimed at improving the flood resiliency of public lands.

The report was commissioned in the wake of 2011’s Tropical Storm Irene, which caused six deaths and $733 million in damage.

The report was commissioned in the wake of 2011’s Tropical Storm Irene, which caused six deaths and $733 million in damage.

Porter argues that the report was “buried” because it was not referenced in the Camel’s Hump management plan. The report recommended limiting logging in headwaters, in which 90 percent of state lands are located. Proposed restrictions included no logging above 2,500 feet or on hills with slopes greater than 35 percent or in thin soils less able to absorb rainfall.

State foresters acknowledged in emails obtained by Standing Trees that if they accepted all the report’s recommendation, it would effectively prevent any logging from taking place around Camel’s Hump.

The report was taken seriously and debated internally among staff, Snyder said.

In response, the Agency of Natural Resources developed a 2016 plan meant to be a blueprint for improving the flood resiliency of state natural areas. It laid out a number of ways to reduce the flood risk on state lands, many of which the state was already doing.

Many involved reducing erosion and flood risks associated with roads, including old logging roads. Decommissioning some roads and installing larger culverts in others were two strategies identified.

Others included helping loggers use portable bridges to cross streams and encouraging them to leave woody debris on the landscape after logging. Many of the improvements would take a significant increase in state funding to accomplish, the report found.

The blueprint did not, however, propose to reduce or significantly alter the way logging is done in the state beyond encouraging flood resiliency to be incorporated into the timber management plans. It noted that many of the measures laid out in the 2015 flood resiliency report were “impractical or may conflict with other important state land management goals.”

“All we are asking is for our state agencies to do what they are required to do,” Mark Nelson, board president of Standing Trees, said in the release. “Because they haven't, we have no choice but to take legal action."

Standing Trees, a Montpelier-based anti-logging group, filed the suit late Wednesday in Vermont Superior Court.

“Public forests are among our greatest bulwarks against climate change and extinction, but they’re being sold to the highest bidder while the public is kept in the dark about how decisions are made,” Zack Porter, executive director of Standing Trees, said in a press release. “If successful, this lawsuit will put the public back in control of public lands.”

The group has called for a moratorium on logging in state parks and forests and in the federal Green Mountain National Forest. It argues that the benefits of leaving maturing forests intact — such as carbon sequestration, clean water, wildlife habitat and flood resilience — far outweigh the economic benefit to the state of allowing logging on public lands.

Standing Trees claims the state Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation relied on outdated science when drafting a plan for logging 3,800 acres of forest around Camel's Hump over the next 15 years. That’s about triple the rate of harvesting in the forest done over the past 25 years.

The group argues that the state has failed to adopt required rules for conducting logging on state lands, essentially allowing state foresters to divvy up chunks of state land for logging as they see fit.

- OURTESY OF THE VERMONT DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS AND RECREATION

- Logging planned around Camel's Hump

The management plan for Camel's Hump, which includes 34 different areas of logging, did go through a public review process. But the group argues that the department follows internal “written procedures” when crafting logging plans that “have never been subject to public comment, public hearing, environmental impact review, consideration of alternatives legislative oversight or judicial review.”

The suit was filed by Bristol attorney James Dumont. Additional plaintiffs are Duxbury residents Jamison Ervin and Alan Pierce, who live on property that abuts Camel’s Hump State Park.

The suit argues that the department was required to go through a public rulemaking process for logging on state lands because it was petitioned to do so by more than 25 people. But the department declined, according to the suit.

The group has also argued that the department ignored a 2015 study that showed logging on state lands needed to be done far more carefully to reduce the risk of flooding due to increasingly intense rainfall driven by climate change.

That claim has "zero merit," Mike Snyder, commissioner of the Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation, said last month.

Snyder could not be reached on Wednesday for comment on the suit. But he has previously accused the group of statutory “cherry picking” and of misstating the department’s planning processes.

The group is essentially reading one section of state law that seems to suggest formal rules are required for timber harvests, while ignoring numerous other areas of law that give Snyder the clear right to manage forests for timber sales, he said.

This includes specific language in the law requiring that what is formally known as the Camel’s Hump Forest Reserve be managed for “sustained production of timber, water conservation, wildlife management, hunting, hiking, cross-country skiing, and nature appreciation.”

- TAYLOR DOBBS ©️ Seven Days

- State forester Jason Nerenberg inspecting a forest in 2018

The first of those sales was scheduled to begin this year, but Snyder said for all practical purposes the sales aren’t likely to be conducted until next year; any logging won’t happen until next winter.

Such timber sales not only generate revenue for the state but provide raw, local material for the state’s forest products industry and improve forest health by creating a diversity of tree ages. Clear-cuts quickly regenerate to create ground cover and habitat for a variety of species, foresters argue.

About 78 percent of the state is forested, one of the highest percentages in the nation. About 20 percent is publicly owned, with 80 percent privately owned. The conversion of private forestland to residential parcels or other uses poses a far greater risk to forests than active logging, Synder has said.

Opponents nevertheless argue that climate change requires an urgent shift in the way the state manages public forestlands.

Over the summer, Porter of Standing Trees vowed to “up the ante and play hardball” to protect state forests to help fight climate change. Earlier this month, the group held a protest outside the Rochester ranger station of the 400,000 acre Green Mountain National Forest. More than 100 activists gathered to condemn a plan to log an area called Telephone Gap around the town of Chittenden.

They held up banners that read "Stop the Destruction" and hiked up to a nearby section of clear-cut forest and lay down in a field of gray stumps beside banners that read “Climate Emergency: Do Not Log” and “No Clearcuts in VTs National Forest.”

The group argues that the forest service logging plans violate the spirit, if not the letter, of President Joe Biden’s executive order earlier this year requiring the service to categorize and monitor old-growth trees on federal lands and to implement “climate-smart management and conservation strategies.”

The majority of the logging slated for the 32,000-acre Telephone Gap area would be trees that are 60 to 119 years old, which Porter said clearly makes them in urgent need of protection.

The group followed up its demand for a halt to the Camel’s Hump logging plan with a public records request that identified a 2015 report aimed at improving the flood resiliency of public lands.

- Courtesy of Zack Porter

- Standing Trees protest

Porter argues that the report was “buried” because it was not referenced in the Camel’s Hump management plan. The report recommended limiting logging in headwaters, in which 90 percent of state lands are located. Proposed restrictions included no logging above 2,500 feet or on hills with slopes greater than 35 percent or in thin soils less able to absorb rainfall.

State foresters acknowledged in emails obtained by Standing Trees that if they accepted all the report’s recommendation, it would effectively prevent any logging from taking place around Camel’s Hump.

The report was taken seriously and debated internally among staff, Snyder said.

In response, the Agency of Natural Resources developed a 2016 plan meant to be a blueprint for improving the flood resiliency of state natural areas. It laid out a number of ways to reduce the flood risk on state lands, many of which the state was already doing.

Many involved reducing erosion and flood risks associated with roads, including old logging roads. Decommissioning some roads and installing larger culverts in others were two strategies identified.

Others included helping loggers use portable bridges to cross streams and encouraging them to leave woody debris on the landscape after logging. Many of the improvements would take a significant increase in state funding to accomplish, the report found.

The blueprint did not, however, propose to reduce or significantly alter the way logging is done in the state beyond encouraging flood resiliency to be incorporated into the timber management plans. It noted that many of the measures laid out in the 2015 flood resiliency report were “impractical or may conflict with other important state land management goals.”

“All we are asking is for our state agencies to do what they are required to do,” Mark Nelson, board president of Standing Trees, said in the release. “Because they haven't, we have no choice but to take legal action."

Correction, November 25, 2022: A previous version of this story misdescribed some of the trees to be logged.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.