- Caleb Kenna

- Jane Beck

Jane Beck has spent most of her 74 years telling other people's stories. The founder of the Vermont Folklife Center has recorded the oral histories of local quarry workers, quilters, farmers, legislators and apple-doll makers. "Our understanding of history in Vermont is much richer because of all these stories that have been collected," said Paul Bruhn, executive director of the Preservation Trust of Vermont, of her work.

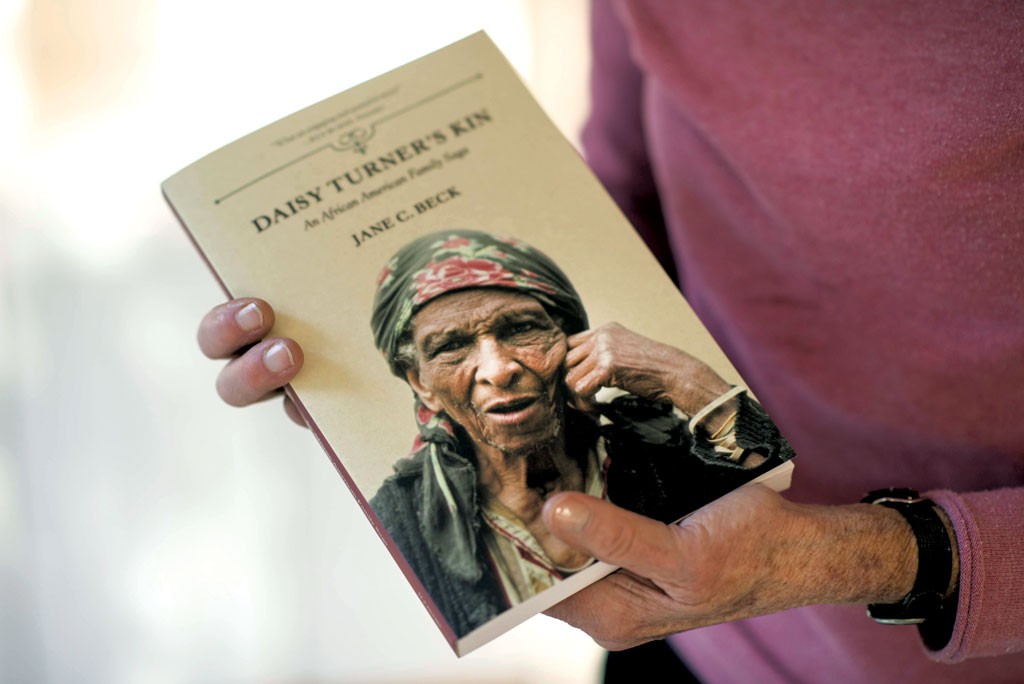

No Vermonter has captivated Beck as thoroughly as Daisy Turner, the daughter of a slave who lived in the Green Mountains until her death in 1988. Now that interest has borne fruit in a definitive scholarly work. The renowned folklorist packed more than three decades of research into her new book from University of Illinois Press, Daisy Turner's Kin: An African American Family Saga, for which she traveled to Virginia, Maine, England and West Africa.

The journey started in Grafton, where Beck first met Turner, then 100, in 1983. For the next several years, the scholar chatted up the cantankerous centenarian, poured her ginger ale, ran her errands and recorded her stories. Beck subsequently brought the Turner family saga to life in audio, film and museum projects. Others shared it in children's books, documentaries and history classes.

Like her father, Turner was a brilliant raconteur — up until the day she died, at the age of 104 — but she also believed in the written word. She was convinced that a book was the best way to commit her family's story to history. She urged Beck to write the tome, advising, "All these things ought not to be lost."

Those words could serve as a guiding motto for Beck, whose work has helped legitimize folklore, lending credibility and respect to a field of scholarship once dismissed as less important than anthropology or history. "She has been very significant on a national level," said Greg Sharrow, Beck's longtime colleague and friend, who stepped up at the Vermont Folklife Center after she resigned as executive director in 2007.

Folklore is basically "cultural heritage," Beck explained — "important to understand because it feeds into who we all are."

Ask who she is, though, and Beck immediately clams up. "I hate it," she said of being the subject of inquiry. "Do we have to get into all of this?" The woman who spent years extracting, verifying and archiving the lives of others doesn't have the slightest interest in talking about her own.

Secondary sources provide some insight into Jane Choate Beck, who grew up in a prominent family on Long Island. Her late father, Thomas Hyde Choate, worked as an investment banker. Her mother, Jane Harte Choate, still appears from time to time on the society pages for her work with the New York Botanical Garden and various charitable organizations.

- Caleb Kenna

When Beck reached her teens, in the 1950s, her parents shipped her off to an all-girls school in Maryland. St. Timothy's School is also the alma mater of Shelburne philanthropist Lisa Steele, who attended about eight years after Beck.

"It was very much like being locked up in jail," Steele said of the place, describing it as a strict, old-fashioned boarding school that was rigorous in every sense of the word. "But we both got through it and, I think, are probably stronger because of it."

Beck graduated near the top of her class at St. Timothy's; her parents wanted her to go to Radcliffe College, but "luckily I didn't get in," she recalled. She happily enrolled at Middlebury College, where she majored in American literature and met her future husband. Professor Horace Beck was two decades older and, like her, an independent sort who chose a simple, rural life over the well-heeled society in which he'd grown up.

"Unpretentious" is the word Steele used to describe Jane, who shared that quality with her husband. Born in Newport, R.I., Horace studied the folklore of the West Indies, and in recognition of his seafaring side, liked to refer to himself as "Swamp Yankee."

Jane graduated from Middlebury College in 1963 and started her graduate studies in folklore at the University of Pennsylvania. She married Horace in 1965. An avid sportsman, he took his new wife duck hunting for their honeymoon. Jane shuttled back and forth between Vermont and Philadelphia to earn her doctorate as they started a family on a farm in Ripton. (Horace Beck would die in 2003.)

Daughter Rowan Beck, a Charlotte resident and public relations director at Bitybean baby carriers, has vivid memories of their family life: a year on a sailboat; lambs in the kitchen; her parents' collaboration on a National Geographic story — Horace wrote the article and Jane took the pictures, earning more money than her husband. "That was a long-standing joke in our house," Rowan recalled. "A picture really is worth more than 1,000 words."

Rowan also remembered her mom chauffeuring children to hockey and skiing and making family dinners — including venison stew — as she built her career. Vermont's first "state folklorist" walked the talk. "It was always very important that we could talk to anybody. My mom is not a showy, glitzy person," said Rowan. "She's very down-to-earth, and she has real, hard-core values. She's more of a Vermonter than she is a New Yorker, and if you're from New York, please don't take offense."

Beck was state folklorist — working for the Vermont Arts Council — when she first heard about Turner. Beck's usual ice-breaking tactic when approaching new research subjects was to get an introduction from a third party; with Turner, that wasn't an option. After writing and calling repeatedly to try to arrange a meeting, she finally got Turner on the telephone, only to be asked sternly, "Are you a prejudiced woman?"

When Beck stammered no, she didn't think so, Turner responded breezily, "Well, come any time."

Beck did, and she was immediately riveted by Turner's stories. Yet even on their second meeting, she was unsure how she would be received. She earned Turner's trust by simply showing up, again and again, refusing to be offended by the old woman's gruff exterior.

Trim, fair-complected Beck has a no-nonsense air. Perhaps her unfussy demeanor appealed to Turner, who lived at the time of their first meeting in a cluttered old house down the hill from the family farm. She was known for ambling around town with a shotgun on her hip.

Beck also brought significant reportorial skills to the table, including persuasion. As Sharrow put it: "It took almost an act of seduction to get Daisy to agree to having Jane visit her."

"She's able to take her time and let people be who they are," Steele observed.

Predictably, Beck's explanation of the "good relationship" they forged is more understated: "I think in the long run, she trusted me as much as she could trust anybody."

Beck went to see Turner at least several times a month for about three years. She learned to make herself useful. As Turner talked, Beck would help her organize papers and fetch things around the house. She steadied Turner into a chair when her legs became weak. And when Turner's health took a bad turn, Beck visited her at the nursing home where she spent her final days.

The hours with Turner contributed to Beck's nuanced understanding of memories and their role in the folklorist's trade. Even when personal recollections aren't factually reliable, she said, they are significant. "It's personal. It's based in emotion," Beck said.

Years after Turner's death, however, translating those recollections into a work of nonfiction proved to be a fact-checking challenge. Beck's book traces the Turner family history from West Africa, where Daisy's grandfather, Alessi, was probably born around 1810, to his enslavement on a plantation in Virginia, where his son Alec was born in 1845. Alec subsequently escaped, served in the Civil War with Union troops and eventually migrated to Vermont, where he raised 13 children.

The creaky home of long-dead plantation owner Jack Gouldin still stands along the Rappahannock River, surrounded by the same spreading fields, according to Beck, who was surprised to find the property remarkably undeveloped. "Alec Turner would recognize it," she said.

Beck also visited West Africa and England to research Daisy Turner's account of Alessi's early years. According to Daisy, her grandfather was the son of an English lady who was shipwrecked and a chief's son who saved her in the surf off the coast of Africa. This would have taken place around 1800.

It sounds more like a romance novel than Roots, but Beck maintains that Turner's recollection is plausible.

Beck spent long hours in England researching shipping company records, passenger and crew logs and accounts of wrecks off West Africa. At one point, she thought she came close to identifying an Englishwoman who could have been the shipwrecked great-grandmother. But the dates and details ultimately failed to match up, and, to her great frustration, Beck was unable to document the identity of either great-grandparent.

She had better luck researching the slave ship that carried the kidnapped young Alessi, later known as Robert Berkeley, most likely to Louisiana. Based on her study of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database and other sources, Beck believes with "99.9 percent" certainty that the ship was the Fenix, a Spanish schooner that transported slaves from Calabar, Nigeria, and environs to New Orleans. Many captives died on the voyage, and the conditions on the ship matched Turner's narrative, passed down from her grandfather to her father, in which it was described as "one of the worst sights that any human being had ever seen — that slave ship."

Throughout Daisy Turner's Kin: An African American Family Saga, Beck points out aspects of Daisy's narratives about the family that she believes to be wrong, half-wrong or impossible to verify. She also documents many parts of the story as Daisy told them and carefully constructs the historical context in fascinating and sometimes grim detail.

The book is not just about facts, though, but about bigger themes and attitudes — from racism to respect to neighborliness. Indeed, part of folklore's appeal for Beck is that it opens a window onto people's views of the world, and "that we understand, that we listen to these attitudes and values and stories. If you can relate to their stories, there's a meeting, a bridging," she said.

Turner's Grafton farm, known as Journey's End, is now owned by the State of Vermont. The Windham Foundation and the Preservation Trust of Vermont are partnering to restore the only remaining structure on the property, a 1911 hunting camp, and to make it a visitor's site.

All the history that farm represents would likely have been lost without Beck, who had the patience and perseverance to draw Turner out. Her work "makes what's left of Journey's End a very special African American site," said the Preservation Trust's Bruhn.

While Alec Turner faced discrimination at times in Vermont, he was accepted and respected by most of his neighbors, and his story in Vermont is a powerful account of the African American experience after slavery. The Turner saga "tells the story of a former slave, a freed man, who came to Vermont by way of Maine and became a hill farmer and, just like lots of white families, struggled in the hills," Bruhn said, summing up Beck's work. "It's really the story of the next step of history of African American families in the United States ... It's a big story."

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.