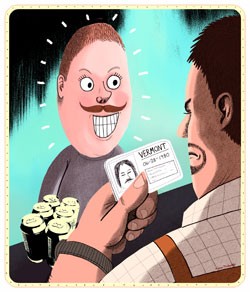

As long as there have been age restrictions on the consumption of alcohol, underage kids have gamed the system to get it. Especially in a college town such as Burlington, the annual influx of students trying to snag hooch illegally is as much a sign of fall as are turning leaves. From the classic “shoulder tap” — asking an older person to buy alcohol — to outright thievery or simply raiding a parent’s liquor cabinet, schemes to get booze run the gamut from creative to desperate. Still, the granddaddy of ’em all remains head and shoulders above other cons: the fake ID.

Matt Gonyo is the Chittenden County investigator for the enforcement arm of the Vermont Department of Liquor Control. He says that in recent years he’s seen a definite increase in false identification cards in Burlington. Gonyo estimates that, through the vigilance of bouncers and retail clerks trained to spot fakes, as well as occasional bar sweeps by the DLC, his department confiscates 300 IDs per college semester — and that’s up significantly from only two years ago, he says. While the increased number of nabbed IDs is a positive, Gonyo adds, the department’s job has become more challenging.

“It’s getting harder and harder for us to do our job effectively, based on the quality of the IDs,” he says.

As technology improves, so does the sophistication of fake IDs. Gone are the days of chalking false numbers on real IDs in your dorm. The new generation of fakes is high tech and, in some cases, nearly flawless.

Specifically, Gonyo cites a website based in the Philippines, ID Chief, that produces IDs of such high quality they are virtually indistinguishable from the real thing. They feature nearly exact replicas of holograms, microscript and watermarks, and use templates that accurately mimic increasingly complex ID designs — which are supposed to make the cards harder to forge. The fakes, which run about $200 apiece, are sold as novelty or “souvenir” items. The website includes a lengthy disclaimer stating they are not to be used as official identification. The problem is, they often can be.

“It’s essentially a valid ID,” Gonyo says. ID Chief allows customers to plug in whatever information they want to appear on the card, including names and addresses. And, unlike other fake ID sites, ID Chief includes a “zip strip” on the back of the card that can be scanned.

“If you walk into a store that has a card reader, and they scan that ID, the reader will tell the clerk you are 21 years old,” says Gonyo.

Mikey van Gulden has had a front-row seat to the evolution of fake IDs in Burlington. The affable bouncer has been a fixture at the front doors of bars in the Queen City for 18 years, and he arguably knows the ins and outs of spotting fakes better than anyone in town.

“Mikey probably knows more about fake IDs than even I do,” says Gonyo.

“In the ’90s, people didn’t have the same access to the Internet,” says van Gulden. “In those days, it was usually something like some guy … making IDs in his dorm room. So you’d see things like IDs laminated to the front of library cards.”

Now, because of sites such as ID Chief, the situation has changed drastically. “Those IDs are the next generation,” van Gulden says. However, he notes, even the new IDs are not foolproof fakes.

“If you know what you’re looking for, you can still spot them,” he says. “They’re just making it a lot harder.”

With the help of local bouncers, including Van Gulden, the DLC has begun to identify minor flaws in the ID Chief design. If a police officer runs an ID from the site through the state database, it will come up as fake. But that process can be time consuming, especially when officers are busting up a large party of underage drinkers.

“If I have 50 kids whose IDs I have to run through our computers to check, that can take a while,” Gonyo admits.

He says that, because a fake ID is considered personal property, bouncers and store clerks are not legally allowed to confiscate them. Yet these IDs routinely end up in the hands of the authorities — how?

According to Gonyo, questionable IDs can be held only to verify authenticity. That can mean a call to a police officer or to an ID hotline run by the VT DLC, 1-866-ITS-FAKE. Once an ID check reaches that point, Gonyo says, the offending underage party often cuts his or her losses and leaves empty handed before the police arrive. Then the ID becomes abandoned property and is fair game for the cops.

Gonyo works with a number of area bars and liquor stores to keep tabs on fakes. Employees at Pearl Street Beverage include a note with each confiscated ID, detailing what the customer intended to purchase, why the ID didn’t pass muster and an occasional personal detail about the ID’s owner. A stop by the store last week netted a stack of IDs about four inches thick — roughly 150 of them — that had accumulated since late June. That’s a decent haul for the summertime, notes Gonyo. One note bore the cryptic description: “Nic Cage.” Another: “Ha! I know this girl. You’re not her.”

Once Gonyo has IDs in his possession, officers can investigate and try to track down the offending minors. He estimates that his office, often with the help of campus police departments, traces about half of the IDs it takes in, and that only about 50 percent of those cases result in citations.

“Really, those are pretty good odds if you’re a minor with a fake ID,” Gonyo concedes. “But it’s still a significant roll of the dice.”

It is. The penalty for using a fake ID to purchase alcohol is stiff: a $288 fine, plus a 60-day license suspension. The same applies to anyone caught furnishing his or her ID to someone underage, which Gonyo says is the most common type of false identity he sees.

“Older brothers or sisters loaning their IDs to underage kids is still the big one,” he says. “We get more of that than anything.”

Gonyo adds that IDs made with laser-jet printers are also common. But they’re easy to spot, because the printer leaves dots that appear under a microscope, which government-issued IDs don’t have — and, yes, Gonyo carries a microscope. Another common flaw: IDs that are too flimsy or too rigid, both flaws usually the result of using poor laminate. Other online companies produce novelty IDs, though generally of poorer quality than those from ID Chief. These tend to be identifiable as fake by bunk watermarks or holograms of words such as “authentic” or “genuine.”

“Real IDs don’t have to tell you that they’re ‘genuine,’” remarks Gonyo.

Van Gulden agrees that the more things change with fake IDs, the more they stay the same, and that older siblings handing down their IDs to younger ones remains the most common form of falsified identity.

“For people who use fake IDs, it’s pretty much a game,” he says. “They realize they have some chance to go to a store or a bar and get away with it. And that’s always been the easiest way to do it.”

That puts the onus on bouncers, bartenders, servers and clerks to size up potential patrons and make the right call.

Gonyo boils it down bluntly: “You just have to take a look at the person in front of you and make a judgment.”

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.