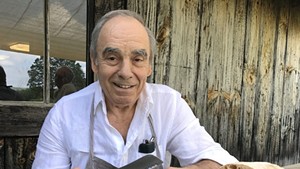

Its noon on Monday and Gerard Rubaud has slipped off his clogs and is sitting with his feet up. It’s the end of his 11-hour work day, and the wooden racks in his bakeshop are crowded with beautiful, brown, crusty, oblong loaves of bread. His baker’s whites are a bit rumpled and he rubs a hand across his forehead and back through his near-shoulder-length hair, but there’s not the slightest hint of fatigue in his crinkled eyes.

Rubaud invites me to sit at the large square table that dominates the room, while he and two young women organize the day’s deliveries.

“Two returns yesterday,” remarks one of the two. Rubaud winces only slightly. This is rare — usually his bread sells out within a few hours, but it’s his policy to take back any loaves not sold the day they’re made.

The women slip the loaves one by one into brown paper bags and load them into wooden crates — no metal or plastic touch either the dough or the finished loaves, because both need to breathe. The 100 to 120 loaves that Rubaud bakes by himself each day — seven days a week, 50 weeks a year — are divided among his eight accounts, some of which get no more than 10 or 12 loaves a day.

“That’s enough, non!' he quips, his French accent softened only slightly by 24 years in Vermont. “My idea is not to run all over the place,” he explains.

As Rubaud sees it, large industrial bakeries end up in the trucking business, spending more money and energy on shipping bread than on baking it. Rubaud has no interest in this; his dream is to be a community baker, and he approaches it with the idealism of a philosopher. “A baker should deliver his own bread,” he says — Rubaud does, two days each week. “If you lose this, you’re not a community baker,” he adds. For him, baking bread is an attitude, a process, a lifestyle. But it hasn’t always been so.

Growing up in the French Alps, Rubaud’s first passion was downhill skiing. His single-mindedness was already apparent as he skied to the exclusion of all other interests — including school. After being tossed out of school for the third and final time at age 13, his father told him, “Okay, you can ski, but you must work.”

Rubaud landed a job as an apprentice in a bakery — not because he particularly cared about baking, but because the early morning hours left him the rest of the day to ski. After a few years, he traveled to Austria for a nine-month stint in a pastry shop. When it came time for his compulsory military service, he completed it by teaching skiing and rock climbing in Chamonix, and left his career as a baker behind him — or so he thought.

In 1964, after joining the French National Ski Team and establishing himself as a prominent ski racing coach, Rubaud was hired by Rossignol to run their race program. Ten years later, Rossignol built their plant in Williston and moved Rubaud to Vermont. “When I was the racing director for Rossi, my goal was to run the company,” Rubaud says. And he did; for several years, he was the president of the U.S. Division of Rossignol.

But after 21 years with the company, Rubaud became disillusioned with the industry and the lifestyle, and he began to look back fondly on his days as a baker.

On business trips to France, Rubaud visited the world-famous Parisian baker Lionel Poilane, whose four-and-a-half pound round country loaves, called boules, had sparked a renaissance in traditional artisanal bread, both in France and abroad. On both visits with Poilane, Rubaud was unable to get the master baker to talk about bread. Instead, he waxed about unrelated topics from American culture and astrology.

Somewhat discouraged, Rubaud left the ski industry anyway, and launched a new food-processing venture in Fairfax, Vermont. Now he prefers not to discuss the details of his eight years devoted to high-quality, vacuum-packed sous-vide foods. Rubaud summarizes, “I should have done the bread thing when Poilane was telling me about the stars.” Instead, he opened Gerard’s restaurant in the Radisson Hotel in Burlington as a showcase for his sous-vide foods.

The concept was revolutionary — a restaurant with no real cooking, sort of a haute approach to “boil-in-a-bag.” But throughout this venture, the lure of bread continued to tug at him. Rubaud began to read anything he could find about traditional bread-making and wood-fired ovens.

During this time, the French government finally lifted the price controls from artisanal breads, which sparked a great resurgence of traditional bread-making in France and the refurbishing of a lot of old community brick-and-stone ovens. Rubaud traveled again to his homeland to visit this new generation of “old-fashioned” bakers and to study their ovens. On one fateful trip, he visited with a third-generation Swiss miller who had formed an alliance with 82 bakers and six farmers in one region. Together, the group formed a fully integrated, self-sustained agrarian community that continues to grow wheat, mill flour, bake bread and nourish itself on these loaves. This became Rubaud's new dream.

In the spring of 1994, with the help of a local mason, Rubaud built his first brick oven. A single-chamber design, the wood is burned direcdy on the floor of the oven so that the flames roll across the top and heat the entire chamber. After six to seven hours, the fire is swept out, and the oven is ready for two to three hours of baking.

At first the oven was a hobby, and Rubaud experimented with baking on weekends. After several months, he began taking some of his bread to the restaurant to serve alongside other local breads. Soon he noticed that diners were picking his bread out of the bread basket and leaving the rest. In July 1995, he closed the restaurant to bake full time.

More than three years later, Rubaud continues to bake the same loaf of bread he started with. Unlike many of the new bakeries popping up everywhere, he’s not tempted to offer different varieties or flavors. The bread is naturally leavened, meaning it is made from a starter (levain) of natural yeasts. Rubaud eschews the word “sourdough,” saying that most sourdough bread is too sour. Instead, his levain is complex and rich. “In a good levain,” he says, “you have 100 different acids — the goal is to find 200.” He also claims to have the best well water in the world. “I could bake with any flour, but without the best water,” he insists, “it’s impossible.”

Over the years, Rubaud has played with the nuances of his formula to achieve a perfect loaf. To illustrate this point, we shuffle across the flour-and-ash patina on the floor to the sacks of flour and grain stacked against the wall. Rubaud tells me about his work with three nearby growers and two millers to produce enough grain locally for his bread. This fall he baked his first loaves using locally grown spelt — his recipe combines organic spelt, rye and wheat. The local grains cost double, but it’s not an issue, Rubaud says. “The cost of making bread is still in the labor, not in the ingredients.”

We look at two samples of spelt berries, one local and one from Canada, which I can barely differentiate. Then Rubaud grinds the two in a small, rickety stone mill — he mills his grain each day at the time of mixing so it doesn’t have a chance to oxidize — and pours them on the table. Still, I can barely make any distinction — until I put my nose down close. The local spelt has more aroma — something between sour and nutty — and it’s darker, moister looking. The difference is subtle, but notable.

It’s the same with Rubaud’s bread. At a time when consumers are bowled over by flavors and extras in our food choices, a loaf of Gerard’s bread may appear under-dressed, but the experience of eating it is a revelation. Simply put, once you’ve tasted Gerard’s, you will understand forever what good bread should be.

Robert Fuller, owner of Leunig’s Bistro in Burlington and Pauline’s Restaurant in South Burlington, recently began to put Gerard’s bread on his menu. “I’ve eaten bread all over the world,” says Fuller, “but there’s just something about that bread — something in its simplicity and its complexity.”

Back at home, I asked my “non-foodie” husband what he thought of the bread I’d brought home from Gerard’s. He held a thick slice to his nose, inhaled deeply and said, “It reminds me of one of my favorite places in the world.” He paused and, anticipating my next question, added, “No place in particular, just a place where I’m in a really good mood.”

With that kind of recommendation, who needs butter?

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.