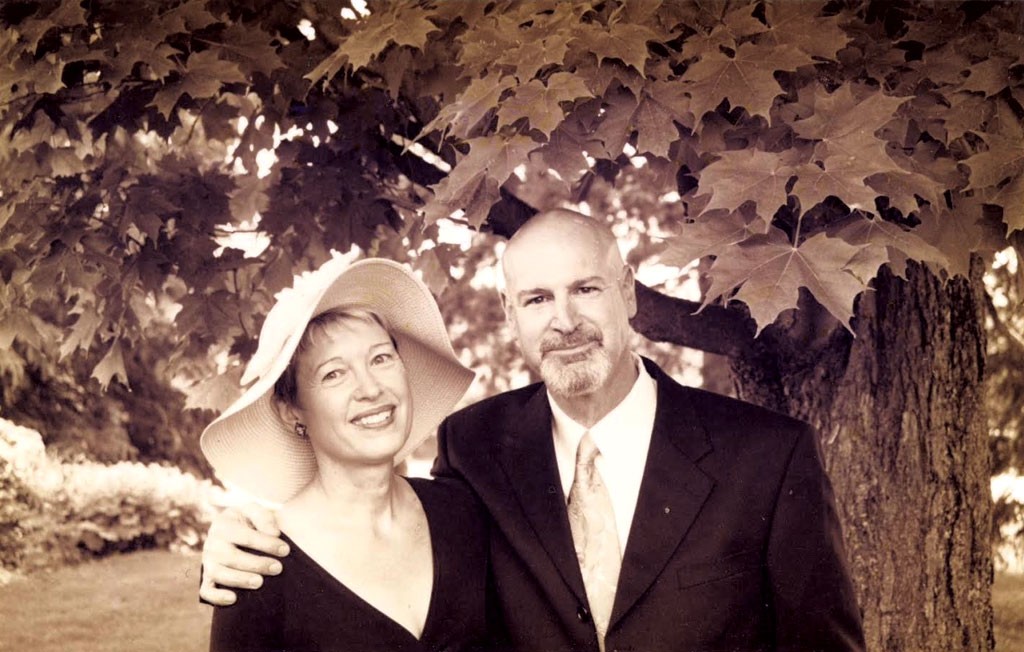

- Courtesy of Polly Young-Eisendrath

- Polly Young-Eisendrath and Ed Epstein, 2001

Vermont psychologist Polly Young-Eisendrath remembers all the questions she aimed at her husband: Why had he racked up some $70,000 in unexplained credit card bills; written another $57,000 in checks to himself from their joint account; and, most disturbingly, anxiously defied her repeated call for answers?

"The bottom has dropped out of everything that promised security in my life," she recalls thinking. "I no longer can count on marriage, finances and any vestiges of control over my circumstances."

Then Young-Eisendrath learned that her husband, Ed Epstein, had early-onset Alzheimer's disease.

- The Present Heart: A Memoir of Love, Loss and Discovery by Polly Young-Eisendrath, Rodale Books, 288 pages. $24.99.

For some, the brain ailment is simply a plot point in dramas such as Still Alice, the current film in which Oscar front-runner Julianne Moore portrays a fiftysomething professor losing her memory. But for an estimated 200,000 Americans, depictions of that impairment hit painfully close to home.

"We knew something was seriously wrong, but when you're in your fifties, you don't want to think of that," Young-Eisendrath says in an interview. "The day he was diagnosed, I had to revise all my plans for the future. I said to myself, Everything has changed. There's no way to fix it. What can I do now?"

Like many clients blindsided by a death, divorce or layoff, the Worcester therapist and writer faced a tidal wave of emotions. She nevertheless found reason to stay with every terrifying yet teachable moment.

"As long as I don't deny my feelings," she remembers telling herself, "I can investigate with a gentle awareness what my life is now presenting me."

A longtime proponent of mindfulness, Young-Eisendrath has trained herself and others to respond to stressful situations with curiosity and matter-of-fact acceptance. The University of Vermont associate professor of psychiatry elaborates on this practice in her new book, The Present Heart: A Memoir of Love, Loss, and Discovery. She reveals how "profound losses are also an opportunity" and intimate relationships can be both "the source of our greatest pain" and "our path to spiritual enlightenment."

Now promoting her work on a national speaking tour, Young-Eisendrath is sharing a personal story that proves truth can be stranger than fiction. Ask the author how she met the object of her affection, and she rewinds to 1969. A 21-year-old Ohio University student at the time, she eyed a fellow young passenger — tall, slender, "his thick black hair rippled down to his shoulders" — on a flight to New York City.

"I noticed you looking at me," he said to her.

She was mulling a marriage proposal from a philosophy professor 15 years her senior, she replied.

"Don't marry that man," he said upon hearing the details. "He's too old for you."

Young-Eisendrath felt attracted to her seatmate, but she nonetheless went off and wed — first the professor and then, after divorcing him five years later, a graduate school instructor. Fast-forward to 1981, when she was teaching at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania. For six months, she sat across from a balding, middle-aged student named Ed. Then, while dreaming one night, the Jungian analyst had an epiphany: He was that suitor on the plane all those years ago.

The two reconnected. Epstein ended his relationship with another woman and told his teacher, "You are the person I want to spend my life with." Struggling with her second marriage, Young-Eisendrath felt extremely conflicted about seeking another divorce. Then she heard Katharine Hepburn speak at the school's commencement. Questioned about her three-decade affair with actor Spencer Tracy, the legendary film star declared, "I have tried to live without regret."

Taking those words as a mantra, Young-Eisendrath divorced her second husband and married Epstein in 1985.

"The conditions in which Ed and I came to love each other are highly imperfect, even offensive to some," she writes in her book. "Of course, in later years, as the richness of our relationship became evident to our friends and family and was witnessed even by strangers, we loved to tell the story of how we met and then lost and then found each other."

For the next 25 years, "Ed was the love of my life," she says, "and we had intimacy on all levels," as well as a blended family of children from their previous relationships. Then, in 2001, 53-year-old Epstein began forgetting things such as appointments, paying bills and putting the cap on the gas tank. One day, Young-Eisendrath relates, she offered to prepare her husband a tuna-salad sandwich.

"I can make it myself!" she recalls him insisting. He told her, step by step, exactly how he'd do it. But he couldn't follow through. Frustrated, Epstein broke down and cried.

It was another seven years before a neurologist at New Hampshire's Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center pinpointed the problem as "advanced Alzheimer's-type dementia."

"I was simultaneously terrified and relieved," Young-Eisendrath says of the 2008 diagnosis. "It wasn't a matter of forgiving Ed for the unbelievable difficulties he'd caused. It was more a matter of becoming conscious."

The doctor wasn't the only one with sobering news. A lawyer, reviewing the couple's shredded finances, advised her to divorce Epstein (to ensure he'd receive Medicaid and she wouldn't be liable for his debts), file for personal bankruptcy and sell their secluded home eight miles north of the Vermont capital.

It all gave Young-Eisendrath pause — meaning, in her case, she took the deliberate act of stopping and sitting still that she has practiced for nearly 45 years, since taking Buddhist vows in 1971.

"My meditation practice has taught me both the means and the value of embracing my immediate experience for what it teaches, and to accept change — even unwelcome change — as the fundamental ground of my life," Young-Eisendrath says. "What I came to recognize is, if you can deeply accept that, you can take any kind of tragedy as a teaching."

Many family members and friends worried that her "Zen attitude" was a way to avoid reality. But the counselor was following decades of dharma study as well as her own instructions to clients: People facing adversity need to move forward, step by step, rather than wallowing in past regrets or future worries.

"Recognize you have a precious human life, and it goes by quickly," she says. "The moment-to-moment appreciation of it is your job. Say to yourself, What's arising now? What's possible now? Then make use of the resources that are available."

So Young-Eisendrath settled until she could clearly see her answer: End her marriage, work to keep her house and devote herself to finding the right care for Epstein.

"After unwelcome change, there is a necessity to tell the event story up to a point," she notes in a handout she distributes on her speaking tour. "That point is at the horizon of when we need to reengage in our lives and change our life story."

While that's far easier said than done, the therapist advises people to drop thoughts of perfection and instead, with self-compassion and patience, seek a clear-headed view of reality.

Young-Eisendrath projects a calm and collected demeanor, but she has endured a flood of wrenching emotions. She details many of them in emails and diary pages excerpted throughout her book.

"Sometimes I feel tremendous anger and resentment about all that is demanded of me," reads an entry from April 24, 2008. "I can hardly allow my feelings to make their way through me; they are so physical. My heart and my throat move in all directions and hurt me in indescribable ways."

Three months later, the tremors shook even deeper: "My life has lately seemed very stark, poignant and something else — I don't know, maybe final," she noted. "I have turned over every rock in terms of being 'Ed's wife' and I am weary of it."

By 2009, Young-Eisendrath had to move her spouse to a nearby care center when he required more support than she could provide. But her responsibilities only grew when, a year later, she opened her door to find her 36-year-old son delivering his 77-year-old father, the retired professor the book names only as Richard, and a surprising revelation. Her first husband, too, had descended into dementia.

"I am overwhelmed with Ed's care and making a living," she recalls saying. "I can help, but Richard cannot stay here."

Yet Young-Eisendrath knew she was the most equipped to deal with memory loss, Medicaid and the reams of related paperwork. Soon she found herself overseeing two ex-husbands — even taking them both out for dinners that she likens to the Mad Tea Party in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

Young-Eisendrath's memoir is as much an exploration of the question "What is love?" as a recollection of the events that caused her to ask. But, like just about everything else in her life, her response may surprise people.

"It's hard to convey exactly why my life continues to feel like such a satisfying adventure even though I watch over two [former] husbands," she writes. "Before knowing Ed, I did not know that such a love was possible; and now, after living with him for decades, I do not want to live without it."

That's why the devoted wife began a long-distance romance with a colleague she identifies simply as Deon — 8,000 miles away in South Africa. She met him at a conference after his wife died of cancer.

"I awoke during the night and involuntarily mulled over the problem of what has been missing in the last five years," she began one email included in the book. "Really, it's been the lack of witnessing that has been so hard. Ed rarely knows where I am, what I'm doing, what is going on in my physical or mental being."

Young-Eisendrath exchanged 2,000 such messages over two years with Deon before she met the man who is now her partner, a New York City psychiatrist whose name she reveals only as Robert.

"I wrestle with myself about the perils of seeking a new beloved," she confides in her memoir. "Frankly, though, losing Ed has sharpened my desire for love and life and my sense of their impermanence."

Young-Eisendrath is not alone. Sharing her feelings at a recent reading at Manchester's Northshire Bookstore, she drew knowing nods from other caregivers of partners with dementia.

"Nobody talks about any of this," she told the audience. "There's a loneliness in those moments of tragedy."

Skeptics may question Young-Eisendrath's positive perspective, but by the end of her book, it's clear this Polly is no Pollyanna. Hard-hit by reality, she chooses with firm conviction to break open rather than apart.

And so she's telling her story to audiences from Northfield to New York to Nashville. She still oversees care for her ex-husband Richard. And she still expresses her love for Ed, though the 66-year-old died on October 15, 2014, just as her memoir began to roll off the press.

"He was in decline, but he was still able to smile and laugh," Young-Eisendrath says. "He said many times, 'This disease is my spiritual teaching.'"

And it is hers.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.