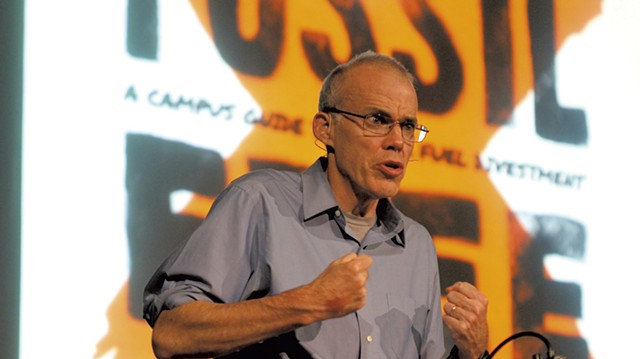

Who knew Bill McKibben could be silly? Yes, that Bill McKibben: the award-winning environmental author and activist, cofounder of the grassroots climate movement 350.org, and the Schumann Distinguished Scholar at Middlebury College. The guy whose 1989 book The End of Nature ushered the alarming idea of global warming into public consciousness. That prescient volume has been published in 24 languages, and McKibben has written more than a dozen others since — all of them nonfiction.

Now comes his debut novel, Radio Free Vermont: A Fable of Resistance. Residents of the Green Mountain State will immediately surmise that the book has something to do with the secessionist movement, and they'll be right. But it has even more to do with creative resistance to an increasingly horrifying direction in which the nation at large is headed — and, yes, President Donald Trump is mentioned by name.

Despite that jarring reference to reality — and McKibben's use of the actual names of Vermont reporters and news outlets — Radio Free Vermont is unquestionably a fiction. Or "fable," as the author would have it. The title refers to a renegade radio "station" of the same name whose motto is "underground, underpowered and underfoot." Its instigator is Vern Barclay, and the book opens with him patching into a tepid acoustic Peter Frampton song that's streaming at a Bennington Starbucks.

The purpose? To remind or inform the customers ordering drinks in "pidgin Italian" that "we still have coffee shops in this state actually owned by Vermonters. Coffee shops where the money in the till doesn't disappear back to Seattle, where the cream in the Mocha-Sexy CappaMolto comes from the cow down the road, and where the music on the stereo might actually come from your neighbors."

Then, before the manager can turn off Vern's illicit message, Grace Potter's voice wafts through the coffee-scented air singing "Ah, Mary."

About an hour north, meanwhile, a Coors beer truck entering the state on Route 22 follows a number of strategically placed detour signs until a balaclava-clad woman stops its driver in the middle of nowhere. Two men quickly relieve the tires of their air and begin to replace the truck's cargo with cases of Vermont-made brew, taking the time to pour out the Coors.

The masked woman hands the driver a picnic to enjoy while he waits: "BLT, with bacon from Vermont Smoke and Cure. A whole pint of Strafford Creamery maple walnut ice cream. And here's something special: a bottle of the new Long Trail Coffee Stout in Bridgewater Corners."

When the driver suggests the mysterious crew could save him time by just dumping the Coors cases by the road, the woman chides him: "'Oh, sweetie,' she said. 'This is Vermont. We recycle.'"

Radio Free Vermont is a sometimes-farcical romp through similarly harmless acts of subversion and Vermont-y clichés. A reader may wonder whether McKibben is gently mocking his endearingly earnest crew or whether he deeply admires their principled stand for what they believe. Most likely, both are true.

McKibben certainly gives us a likable protagonist in 72-year-old Vern, who broke away from "big radio" and is now illegally breaking into its bandwidth like a modern-day Ethan Allen of the airwaves. A hacker in hiding, he's using the medium to advocate for the simple — and simply threatening — idea of Vermont's independence from the United States.

It's not just the corporatization of media that bothers Vern. Covering the opening of a new Walmart for his big-radio employer, "I felt like I wasn't in Vermont anymore — my own idealized Vermont, where what mattered were your neighbors and your values," he explains.

The powers that be were not happy with his rebellious response, and now Vern is a wanted man.

Among his compatriots in subversion are Sylvia Granger, who runs the School for New Vermonters; dreadlocked, on-the-spectrum computer genius and soul-music lover Perry Alterson; and female state biathlon champion Trance Harper. But Vern is the conscience and soul of the book. He's seasoned enough to remember the old Vermont, smart enough to see that "bigness" has not been all good and pragmatic enough to understand that "stunts" will not suffice to change minds.

"I think we've gotten so used to the idea of the big enormous nation that we're a tiny part of, that it would scare most people to even imagine breaking away," Vern tells Perry. "Like an eight-year-old running away. We need to convince folks that we're eighteen now, and it's time to strike out on our own."

The storyline of Radio Free Vermont confronts this grassroots band of rebels with a genuine threat. In the end, their accomplishment is not secession but another kind of victory. McKibben's message is not really that Vermonters should hightail it out of the Union. Rather, it's that the state's residents should hold tight to the values that made its founders fiercely independent in the first place and hew to the scale that makes that independence possible.

As Trance puts it near the book's end, "I've heard those great jets the president was talking about, and they may have their place, but here in Vermont the sound of freedom is low, quiet, small. It doesn't drown out everything else."

From Radio Free Vermont: A Fable of Resistance

- Steve Liptay

- Bill McKibben

"Here's what you need to know about Ethan Allen," said Vern. "He was a remarkable man, but he wasn't exactly a patriot in the Washington mold. He was a common man. Like a lot of other people, he'd bought a piece of land in Vermont — the colonial governor in New Hampshire was making himself a lot of money selling titles. The trouble was, the colonial governor of New York thought everything east of the Connecticut River belonged to him. And he had enough pull to get the king to agree. So the New Hampshire grants were ruled invalid, and New York started reselling the land to speculators.

"Ethan Allen went to Albany for the great court battle, but it was a put-up job. The judges were puppets; they held that all the people farming Vermont had to buy their land again, this time from the New Yorkers. The next day the attorney general of New York visited with Allen, and told him to go tell his friends to make the best terms they could with their new landlords. His advice came with a veiled apology and a veiled threat: 'Might often prevails over right,' he pointed out, with the confidence you'd expect from a representative of the mightiest empire on earth. Ethan Allen looked at him and said, 'The gods of the valleys are not the gods of the hills, and you shall understand it.' And he headed home.

"When he got there, he assembled the Green Mountain Boys — remember, these were men faced with losing their land. And they passed a resolution, I'm quoting from memory here, resolving to protect their land from the New Yorkers 'by force, as law and justice were denied them.'"

"So is that us?" Sylvia asked. "By force?"

"Not too likely," said Vern. "I mean, I'm an NRA guy since my first deer rifle, and Trance can shoot better than anyone in the state, but something tells me we're likely to be outgunned. Old Ethan could pretty much fight the New Yorkers even up, and once he'd stolen that one cannon, it was enough to force the British out of Boston. He didn't have to worry about, oh, I don't know, helicopters. Or Predator drones. Some lieutenant sitting in the Nevada desert could put a missile down our chimney with a joystick, and then go coach afternoon practice for his daughter's soccer team. And anyway, our chief strength is that people kind of like us. They think we're sort of funny, and maybe even a little noble. And I imagine that would end right about the moment we shot someone."

"My chimney was just relined," said Syl. "It cost a fortune."

"I've got an idea," said Trance.

Seven Questions for Bill McKibben

Reached in Los Angeles last week on his book tour for Radio Free Vermont, Bill McKibben said he's been on the go for weeks. Earlier this month, he was at Carnegie Hall in New York City for a concert promoting Pathways to Paris. That's a "collection of artists, activists, academics, musicians, politicians, innovators coming together to fight for climate justice," according to its website.

McKibben joined fellow activist Vandana Shiva and musicians such as Patti Smith, Michael Stipe, Joan Baez and Cat Power to announce, in partnership with Vermont-based 350.org and the United Nations Development Programme, a new project called 1000 Cities. It invites all the cities of the world to transition to 100 percent renewable energy by 2040. Another reason for his visit to New York, McKibben said, was his effort to get the state to divest from fossil fuels.

Events like this, along with appearances to promote his new novel, keep McKibben away from his home in Ripton all too frequently. But for a guy who's trying to save the world — or at least the environment — that's par for the course.

McKibben graciously took some time to talk to Seven Days, noting he'd be home in time for Thanksgiving — and another talk at Phoenix Books Burlington.

SEVEN DAYS: When you address audiences on the West Coast, or anywhere outside Vermont, about this book, do you have to tell them about our little state's secessionist efforts?

BILL MCKIBBEN: No — the secession part is just a plot device. But I do have to tell them about town meeting. That's important to the mind-set of Vermont. The interesting question is, how is Vermont different? What would happen if someone like Donald Trump talked at town meeting — it's inconceivable.

I think Bernie [Sanders] had it more or less right, though: We don't need to secede; we need to resist. This book is a part of the resistance that I've been part of for a decade.

SD: This is a two-part question: You've written a number of nonfiction books. Why not write the very real secessionist story as nonfiction? Also, which came first for you — the topic or your desire to delve into fiction?

BM: I've written about the topic — it's about bigness and scale, etc. — as nonfiction. I'm definitely drawing on some of that in places here. One of the great pleasures is, I was allowed to be a good deal funnier. Most of my time, I've just bummed people out.

SD: I have to say, it's a fun read. Was it more fun for you to write than your nonfiction, more reportorial books?

BM: Absolutely. One of my jobs out of college was writing "The Talk of the Town" for the New Yorker. This reminded me of that, to some degree. I'm glad other people have found it funny.

SD: How else was it different?

BM: When you're a journalist, it's always annoying that people don't give you the perfect quote. In fiction, they always do.

SD: Overall, what would you say the mission of this book is? What do you want readers to take away from it?

BM: I hope people enjoy it and laugh. I think we're all due for a laugh. If ever there was a year to publish a funny book, this is it. And I hope it inspires people to think creatively about ways of resisting.

If you want to learn how to fight a war, there are enormous possibilities, from going to West Point to reading Tom Clancy. To resist, people have to just make it up as they go along. That's what we've had to do at 350.

SD: Would you be in favor of Vermont seceding from the Union, particularly if things keep going the way they are right now?

BM: Vermont might be one of the hardest places to secede — we're one of the oldest states. If you threaten to cut off Social Security, you'd be in trouble.

I do think the time is probably overdue for looking at how we set up some of the basic systems [of the country]. I say that reluctantly; in high school, my job was giving tours in [historic] Lexington, Mass. I'm very fond of this country.

I really do think scale matters. Small is not just beautiful but may be sustainable.

SD: Any other fiction books — or fables, as you put it — in your future?

BM: I hold out the hope that I will someday write stories — when we decisively defeat climate change.

I am working on a long and depressing book — we're coming up on the 30th anniversary of The End of Nature. I'm looking at an assessment. I was 27 when I wrote that. More than half my life has been devoted to doing this work. We're fighting, but we're losing.

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.