- Associated Press

- Bernie Sanders (right) celebrating his 2006 electoral victory with his campaign manager, Jeff Weaver

Sanders activated his loyal network of small-dollar donors and built out a robust campaign infrastructure. He played tough behind the scenes but kept his public remarks focused on his well-worn message of economic equality — drawing a not-so-subtle contrast with his self-funded rival. “Together, we will help make government work for all of the people, and not just the wealthy and the powerful,” Sanders pledged.

The opponent in question was not Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire businessman and former New York City mayor who is running against Sanders for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination. It was Republican Rich Tarrant, the millionaire software executive who unsuccessfully challenged Sanders for Vermont’s open U.S. Senate seat in 2006.

Though the races differ in scale and consequence, those who took part in the 2006 contest — the most expensive in Vermont history — say it offers clues as to how Sanders may take on Bloomberg in the coming weeks or months. “It will be class warfare, and it will be vicious,” predicted Dave Carney, a veteran GOP operative who consulted for Tarrant that year.

- Associated Press

- Republican Senate candidate Rich Tarrant conceding

“Bernie has been through the experience of going up against somebody with unlimited resources,” said Tad Devine, a former Sanders political consultant who produced ads for him that year. “The question is: Is Bloomberg gonna do what Tarrant did?”

At last week’s debate in Las Vegas, the answer appeared to be yes. In his debut on the big stage, Bloomberg wrote off Sanders as unelectable and equated his self-described democratic socialism with communism. “What a wonderful country we have!” Bloomberg exclaimed. “The best-known socialist in the country happens to be a millionaire with three houses. What did I miss here?”

Whether Bloomberg will amplify such attacks in his ubiquitous television commercials remains unclear. According to the tracking firm Advertising Analytics, the billionaire has already spent more than $420 million on TV, radio and digital ads. To date, the vast majority of his spots have burnished his own record or tarnished that of Republican President Donald Trump, but in the past week he has released digital ads tweaking Sanders and former vice president Joe Biden.

Sanders, meanwhile, has been following a familiar playbook. Campaigning in Nevada last week, he characterized Bloomberg as nothing more than a power-hungry oligarch. “He’s going to try to buy the presidency — by spending hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars on TV ads,” Sanders said. “Well, I got news for Mr. Bloomberg, and that is: The American people are sick and tired of billionaires buying elections.”

Fourteen years earlier, Sanders employed a similar strategy. “Our challenge was to turn Tarrant’s main advantage — his money — against him,” Sanders’ longtime campaign manager, Jeff Weaver, wrote in his 2018 memoir, How Bernie Won. “We had to make every one of his innumerable ads a reminder to our fellow Vermonters that Tarrant was the candidate of big money and Bernie was the candidate of the average person.”

According to Phil Fiermonte, a former Sanders aide who ran his field program in 2006, that directive led to the campaign slogan, “Experience That Money Just Can’t Buy.”

Like Bloomberg, Tarrant came from a working-class family. The New Jersey native was the son of Irish immigrants and came to Vermont on a basketball scholarship at Saint Michael’s College. After the Boston Celtics drafted and then quickly cut him, Tarrant took a job with IBM selling computers in the Northeast Kingdom. In 1969, he cofounded the technology company that would become IDX Systems and, 36 years later, sold it to General Electric for $1.2 billion. Tarrant was not available to comment for this story.

Unlike Bloomberg, who spent 12 years governing the biggest city in the country, Tarrant was a political novice when he decided, in 2005, to seek the U.S. Senate seat being vacated by Republican-turned-independent Jim Jeffords. According to Carney, everyone involved in Tarrant’s campaign knew that it would be “an extremely uphill fight.”

Sanders, an eight-term member of the U.S. House and former mayor of Burlington, was universally known in Vermont and, therefore, hard to redefine. “Everybody had an opinion on him,” Carney said. “They either loved him or they hated him. There wasn’t anyone in the middle.”

That wasn’t the case for Tarrant. Sanders’ staffers quickly set about branding him as an out-of-touch and out-of-state elitist. “We went on the offensive right out of the gate,” Weaver wrote, suggesting that the campaign played a part in seeding stories about Tarrant’s Florida homes and part-time residency.

Sanders had a sympathizer in the late Seven Days political columnist Peter Freyne, who christened the “gazillionaire” Tarrant “Richie Rich” and chronicled his $8.9 million Florida mansion, $156,000 Bentley Coupe GT and “amazing, self-funded, televised ego trip.”

Sanders and his aides often claim that he has never run a negative ad. He hasn’t needed to, in Carney’s view, because the press has always done his bidding. “Bernie’s people were very nasty, very negative,” he said. “They actually used your newspaper to try to disrupt and discredit Rich every week.”

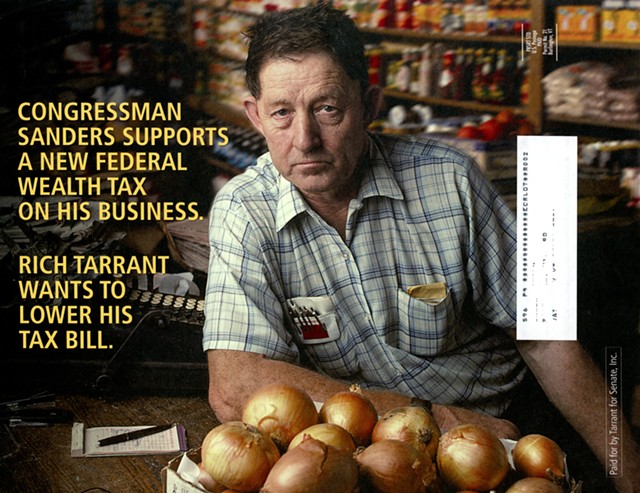

Tarrant was far more overt. For months, he had tried to improve his standing with a series of slick biographical ads illustrating, in episodic fashion, his rags-to-riches story. When those failed to do the trick, he went on the attack.

- Courtesy of the Vermont Historical Society

- A Rich Tarrant mailing to voters from the 2006 election

In fact, Sanders had opposed a 2003 bill that set up a national coordinator for the Amber Alert child abduction emergency notification system, citing an unrelated provision that he argued would have limited the discretion of federal judges during sentencing.

The ad quickly backfired. “I’m sure they tested well in polling, but in practice people were never going to believe that Bernie was on the side of sex predators and kidnappers,” recalled Jim Barnett, a political operative who chaired the Vermont Republican Party at the time.

According to Devine, the campaign had been anticipating incoming fire — if not an attack of that nature — and had already filmed a canned response. It was as close as Sanders came to direct criticism of Tarrant’s wealth. “For months, my opponent, Rich Tarrant, has been spending millions telling us about himself,” Sanders says in the direct-to-camera spot. “Well, it’s his money and he can spend it if he wants, but he has no right to distort my record or what I stand for.”

Rather than get into a “rat-a-tat-tat” with Tarrant, Sanders decided to keep it positive, Devine said. His next ad featured country singer Willie Nelson endorsing him at a Charlotte farm. “If you keep Bernie in there, it’s gonna be better,” Nelson drawls in the ad.

To keep up with Tarrant’s spending, Sanders took the unusual step of holding fundraisers across the country. But it was his direct mail solicitations that really brought in the dough. According to Fiermonte, the campaign would buy lists of mailing addresses belonging to, say, subscribers to the lefty magazine the Nation and send each household a four-page fundraising letter penned by Sanders. “This is something that Bernie really spent a lot of time over the years developing: a progressive direct-mail list,” Fiermonte said. “I don’t think there was anything that rivaled it at the time.”

By the end of the campaign, Sanders had raised an astounding $5.4 million — not quite as much as Tarrant had dropped, but enough to stay competitive.

“That was a really eye-opening campaign in that you started to see the power of these individual donors who kept giving and giving and giving and never reaching the maximum,” said Bill Lofy, who ran the Vermont Democratic Party’s coordinated campaign that year. “It foreshadowed a totally different way of raising money.”

Sanders made another big change in 2006 that presaged his future runs for the Democratic presidential nomination. After decades of squabbling with Vermont Democrats, he for the first time sought the party’s nomination and endorsement, which froze out other potential Democratic candidates. Sanders won the nomination, declined it and ran in the general election as an independent. But he also for the first time took part in the party’s coordinated campaign, a biennial effort to pool Democratic resources and join forces on list-building, phone-banking and advertising.

“I think it was just pragmatism,” Lofy said. “He’s a very smart politician.”

In the end, Sanders walloped Tarrant, 65 to 32 percent. In Barnett’s view, “Rich never stood a chance.” With George W. Bush in the White House and the Iraq War going south, Republicans throughout the Northeast were decimated. And Tarrant hadn’t done himself any favors by going nuclear on a known and trusted incumbent.

“That flushing sound you just heard, folks, was a certain retired software millionaire’s ego and reputation going down the toilet,” Freyne had written months earlier, declaring Tarrant’s campaign all but dead after it aired the Amber Alert ad.

Whether Bloomberg will suffer a similar fate remains to be seen. If his performance at last week’s debate is any indication, he may be as poor a campaigner as Tarrant was.

One thing that is clear, in Devine’s view: Sanders knows what it takes to face “one of those I’ll-spend-what-it-takes kind of guys.”

“He’s been through this, and he navigated it very successfully,” Devine said. “He didn’t freak out. He stayed the course.”

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.