- Ben Deflorio

- Inside Vermont Tech's advanced manufacturing laboratory

If Vermont manufacturers could design and assemble the ideal employee to join their future workforce, that person would look a lot like Ethan Guillemette.

The 24-year-old, who's built like a defensive lineman, grew up working on his family's 200-head dairy farm in Shelburne, where he learned to take apart and repair farm implements when they broke down. If his father or one of his uncles wanted to modify or improve a piece of equipment, they'd design and rebuild it themselves, as Guillemette did for his high school senior project: a 16-foot trailer he constructed from scratch. When Guillemette wasn't studying or working on the farm, he drove an 18-wheeler for Bellavance Trucking in Barre.

Such hands-on skills are increasingly rare, but manual dexterity alone doesn't explain why Guillemette, a newly minted college grad, has a wealth of job prospects to choose from. He's in demand because he also knows how to program and operate a CNC, or computer numerical code, controller to run tools such as lathes, mills, routers and grinders. He understands the fundamentals of thermodynamics, electrical conductivity, fluid dynamics, and the statics and strengths of different materials. And he can program a brand-new robot to do a "handshake," or interaction, with a milling machine that was built 30 years ago.

In short, he understands and speaks the language of advanced manufacturing. That means he can take a product from concept to design to prototype to mass production — skills that are highly valued in today's high-tech manufacturing environment.

Guillemette is one of 10 students who just graduated from a new degree program at Vermont Technical College; the four-year bachelor's of science in manufacturing engineering technology is the first of its kind in Vermont. Every member of the inaugural class has at least one job offer.

The course of study is meant to address the single biggest challenge facing the state's advanced manufacturers today: a widening skills gap between their personnel needs and those that the typical high school or college graduate can deliver.

That mismatch is "only getting bigger — significantly bigger," said Chris Gray, an assistant professor in Vermont Tech's department of mechanical engineering technology who teaches in the program.

Gray said that Vermont wants its middle-schoolers to understand how their geometry and algebra classes are applicable to fields such as advanced manufacturing so that by the time they get to high school, they'll have many more career options.

"We're thrilled to see this program actually become a reality," Bob Zider, director and CEO of the Vermont Manufacturing Extension Center, said of the new Vermont Tech degree. "I think it will help address the needs of our manufacturing community in a better way."

- Ben Deflorio

- Ethan Guillemette

In the last year, there's been plenty of public discussion and media coverage about U.S. manufacturing going to other countries, especially Mexico, China and India. In 2016, then-presidential candidate Donald Trump made the loss of American factory jobs a centerpiece of his campaign — and, based on his victories in the Rust Belt states of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan and Wisconsin, that message clearly struck a chord with thousands of blue-collar voters.

But the widespread outsourcing of U.S. manufacturing jobs to more cost-effective plants overseas is only part of the story. Economists point out that many other positions were lost, not to cheap foreign labor, but to computers, robots and automation. As Sean Gregory notes in his May 29 Time magazine article, "The Jobs That Weren't Saved," robots now perform about 10 percent of all manufacturing worldwide, a figure that's predicted to rise to 25 percent by 2025.

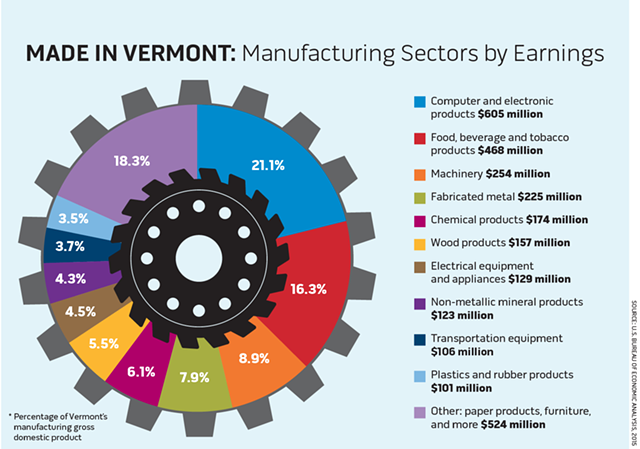

In Vermont, similar trends are reshaping manufacturing, the state's largest private-industry sector, which comprises nearly 10 percent of its gross domestic product. In 1997, 44,000 Vermonters worked in manufacturing, according to VMEC figures. By 2010, the number had fallen to 31,000 — about a 25 percent decline.

But as Zider pointed out, average worker productivity during that same time period actually rose by about 70 percent. In short, the average Vermonter employed in manufacturing produced about 2.5 times more in 2010 than he or she did in 1997.

Most of those advances, Zider noted, resulted from improvements in manufacturing technologies as well as the adoption of so-called "lean manufacturing" techniques — the term for producing goods faster, cheaper and more sustainably without sacrificing quality. But in order for local companies to keep pace with those technological advances, they need highly trained workers who understand the processes behind them, such as injection versus extrusion molding and pneumatic versus hydraulic systems.

Cathy Tempesta is director of human resources at GW Plastics in Bethel, an advanced manufacturer of products for the medical devices and automotive safety industries. She said her company, like many others in Vermont, needs to reverse a lot of outdated or inaccurate stereotypes about the word "manufacturing." For years, she said, middle and high school students have been told by parents or school counselors that it meant either working in a mindless, dirty and dead-end job on an assembly line — or it required a PhD in electromechanical engineering or computer science to build robots and artificial intelligence. As school districts have looked for ways to trim budgets, many have eliminated vocational training.

"So we kind of fell off the map," Tempesta said, "and our traditional ways of recruiting stopped working."

Two years ago, GW approached Vermont Tech to help alter those perceptions. As part of the company's long-term strategic plan to grow its local workforce (see below) it decided, in the words of VMEC's Zider, "to put some skin in the game." GW donated $35,000 toward Vermont Tech's new Advanced Manufacturing Laboratory, one of five new manufacturing labs on the Randolph Center campus.

It was quiet and student-free last week during a tour of Vermont Tech's new $2 million manufacturing training facility. "Shop class" doesn't look the way it did 20 years ago. The half dozen Bridgeport milling machines all have brand-new, 2017 CNC controllers like those in many manufacturing facilities around the country.

- Ben Deflorio

- Christopher Gray (right)

As in most modern plants, Vermont Tech's has an open floor plan, which allows students to reconfigure their workspace for the specific tasks at hand. In one corner, an industrial plastics training machine is nowhere near as large or complex as those found 10 miles down the road at GW. Still, Gray said the machine is ideal for teaching students the various methods used in making molded plastic products such as pill bottles, screwdriver handles and Frisbee golf discs.

At another workstation, Gray showed how his manufacturing students created an automated process to build handheld maze games for kids, designed to look like the classic Nintendo Game Boy, only without any electronics.

As part of that senior project, Gray explained, the students had to create an "automated lights-out assembly process." In layman's terms, that means that, at the touch of a button, the system would work through the night without any human intervention — hence the "lights out" — to produce a series of parts for the next day. The project, which involved about 500 hours of labor, included teaching a 20-year-old CNC milling machine to communicate with a brand-new robot.

While the students slept, the robot would grab a piece of aluminum out of a feeder, drop it into the milling machine and cut a maze pattern. Next, the robot would flip the aluminum piece over, cut another maze, then drop it on a visioning system for inspection the next day.

"What we're trying to encourage ... is: Think process, not product," Gray explained. "What are the processes that go into what they're making?"

In an adjoining laboratory, students learn inspection and metrology, or the science of measurement, which are necessary both for designing parts and ensuring their quality. Though incoming freshmen don't necessarily need advanced calculus in order to succeed in this program, Gray said, they do need to understand that mathematics is the language of engineering.

"There's an old saying in manufacturing," he said. "You can't build something unless you can measure it."

In another laboratory, Gray showed off the jigs and fixtures his students came up with as part of an arrangement that lets them work on actual projects for Heco Engineering in Essex Junction (see below). This job was complicated: The purpose of the device couldn't be revealed to the student engineers because the final product hadn't been patented yet. Eventually, they learned that it was a device to repel bats from wind turbines.

In the next lab, Gray showed off the school's new water jet, the only one of its kind in an academic setting in Vermont. This $100,000 piece of machinery uses a mixture of granulated garnet and high-pressure water, shot through a nozzle at 30,000 to 40,000 pounds per square inch, to cut through anything from aluminum to six-inch industrial steel.

Gray's graduating seniors used this huge cutter to mass-produce Vermont Tech key chains, which the students later sold to raise money to buy more equipment.

With manufacturing technology changing so rapidly, how does Vermont Tech intend to remain up-to-date on the latest industry practices? Gray, who's spent the last 32 years straddling industry and education, emphasized that this program is not about memorizing code or knowing how to operate the most state-of-the-art machinery. It's about training students to solve practical, real-world problems.

"Because of the way Vermont Tech teaches, you learn the process from start to finish," Guillemette said. "That way, you can be more useful as a designer, as a toolmaker, because you know how it all has to come together. Not only is it enjoyable for me, but I can see a finished product afterward ... This is what I've always wanted to do."

Policymakers are already on board. Hours before the tour, Gray attended a meeting entitled "Pathways into advanced manufacturing" with Vermont Tech president Pat Moulton and Secretary of Education Rebecca Holcombe.

The old educational model, in which college-bound high school students didn't "waste their time" on vocational training, is being turned on its head. Holcombe described Vermont Tech's advanced manufacturing program as "an ideal nexus" for "building new career pathways" and "boosting workforce preparation opportunities" for students interested in technical fields.

Those fields already provide some of Vermont's highest-paying jobs. In 2014, the average wage in manufacturing in Vermont was $55,290, about 29 percent higher than the statewide average wage of $43,017. Benefits tend to be generous and often include creative perks such as yoga classes and fly-fishing clinics (see below).

According to Zider, every dollar of goods manufactured in Vermont generates an additional $1.40 in economic activity and supports another 4.9 jobs. "If you look at the whole supply chain," he added, "they need legal support, accounting support, marketing support, so ... this is an enterprise that has tentacles out there touching all facets of our economy."

During the summer, Gray works for the American Precision Museum in Windsor. There he likes to remind visitors of Vermont's role in the Industrial Revolution. It was at the Robbins & Lawrence factory in Windsor, he said, where the world's first interchangeable parts were made, giving rise to the country's precision machine tool industry.

About 60 percent of the rifles used in the Civil War were designed and produced in Windsor. During World War II, Gray added, Adolph Hitler drew up a list of potential targets to bomb on the East Coast. According to local lore, the cluster of Vermont manufacturing plants known as "Precision Valley" was on it.

Green Mountain factories may not be in the crosshairs of America's adversaries today, but whether they produce socks, cheese, ice cream or drug-delivery devices, Gray pointed out, each is engaged in a form of manufacturing.

"For an economy to grow, you've got to make something," he said. "If we do anything well at Vermont Tech, it's preparing students for change ... What they're going to be doing in five years hasn't even been invented yet."

GW Plastics: Molding Its 21st-Century Workforce

- Ben Deflorio

- GW Plastics

Headquarters: Bethel

Workforce: 1,100 worldwide, including 400 in Vermont

2016 sales: $155 million

The tiny Vermont mill town of Bethel hosts some of the most advanced plastics manufacturing in the world. On the production floor at GW Plastics, clear Plexiglas boxes the size of cargo vans contain high-speed robots that interact with computerized injection-molding machines in a meticulously choreographed dance.

Each workstation produces plastic components that will later be incorporated into larger finished medical and automotive products: the flexible grips for surgical staplers, parts for contact lens cases, safety mechanisms used in seatbelt-retraction devices. Each part must meet the customers' precise design specs to one-thousandth of an inch.

"These molding machines are like trophy homes on Lake Champlain," said Brenan "Ben" Riehl, GW' president and CEO. "They can go for anywhere from $300,000 to over a million a pop."

The employees who operate the equipment wear white coveralls, hairnets and safety glasses. Peer beneath their protective garb and you'll notice something telling about GW's workforce: Many are nearing, or beyond, typical retirement age, including 87-year-old Bill Wells, who's worked for the company for decades. Riehl said that in the last two years alone, he's given out at least five 50-year service awards to GW employees.

Though staff longevity is an asset and longtime workers are invaluable in mentoring newer workers, Riehl acknowledged that both could be liabilities — were the company not laying the groundwork for future labor needs.

"We're an advanced manufacturer and we need a highly skilled workforce," he explained. "If we try to recruit our way out of it, it's not gonna happen."

To that end, GW has invested considerable time, energy and resources in the last few years to create an educational "ecosystem" in central Vermont to populate its future workforce. It starts at the high school level, continues through Vermont Technical College's bachelor's of science degree program in manufacturing technology and extends into GW's current workforce.

GW has a long history of innovative thinking. The company was founded in 1955 by early plastics pioneers John Galvin and Odin Westgaard — hence the GW in the name. There was no logical business reason to locate the company in Vermont, Riehl noted, but both men enjoyed hunting, fishing and skiing. According to company lore, the two were returning from a fishing trip in Canada when they stopped at Tozier's Restaurant in Bethel, and someone invited them to drop their lines in the nearby White River. They fell in love with the area, and GW has been headquartered in a converted Bethel dairy barn ever since.

Through the 1960s and '70s, GW became known as a contract plastics manufacturer for large multinational corporations that included Polaroid, Gillette and IBM. In the early 1970s, Westgaard sold his share of the business to Galvin, who later sold to the Carborundum Company of Buffalo, N.Y. Then, following a series of corporate acquisitions through the late '70s and early '80s, GW suffered from what Riehl calls "large-company neglect."

In the early '80s Riehl's father, Frederic Riehl, a chemical engineer, was hired as GW's general manager. Six months later, when presented with an opportunity to buy the company outright from Standard Oil of Ohio, the elder Riehl quickly assembled a group of investors and took the company private in 1983. In 1989, Ben Riehl went to work for his father, who still chairs GW's board of directors.

In 1983, GW had just 140 employees. Today, it has 1,100 spread among four U.S. facilities — Bethel, Royalton, San Antonio, Texas and Tucson, Ariz. — and two foreign plants, in China and Mexico. Why stay in New England? As Riehl pointed out, GW's entire senior management team lives in Vermont or New Hampshire and is committed to maintaining its Green Mountain presence.

Like most American manufacturers, GW has struggled to fill its high-tech positions. But rather than "sitting on our hands," said Riehl, and waiting for others to solve its problem, the company decided to tackle its workforce shortage head on.

In years past, Riehl explained, GW offered scholarships to local high school students. Though they were good for the company's public image, they didn't return much bang for the buck, as most of those students left Vermont and never returned.

So in 2015, the company founded its "School of Tech" program, a semester-long class for local high school students starting in the ninth grade. They spend three days a week at GW learning about polymer science, product design, injection molding, automation, quality assurance and general business skills. The class includes a visit to Gifford Medical Center in Randolph where students get to see GW's medical devices in action.

GW has also invested heavily in Vermont Tech's manufacturing degree program. In addition to funding its advanced manufacturing labs, GW now offers full scholarships and paid summer internships to Vermont Tech students. Assuming those students perform well, Riehl said, a high-paying job with benefits that are "second to none" in Vermont, awaits them upon graduation. GW just hired three from Vermont Tech's class of 2017.

The company has also created a Technical Leadership Program that identifies current GW employees who never attended college but wish they had. Those staffers can now earn an associate's degree in mechanical engineering at Vermont Tech — and GW fully reimburses their tuition. Once they graduate, GW gives them a 10 percent pay increase.

GW's investment in educating its workforce pays its own dividends. Before an employee completes the company-funded associate's degree, each must devise an innovation that saves GW money — then present that idea to senior management. So far, seven employees have completed the program, including a pair of brothers.

"Neither of them had graduated from college, so this was a big deal for them," Riehl said proudly. "And, it was a big deal for us, too."

— K.P.

Heco Engineering: A Modern 'One-Stop Shop'

- Matthew Thorsen

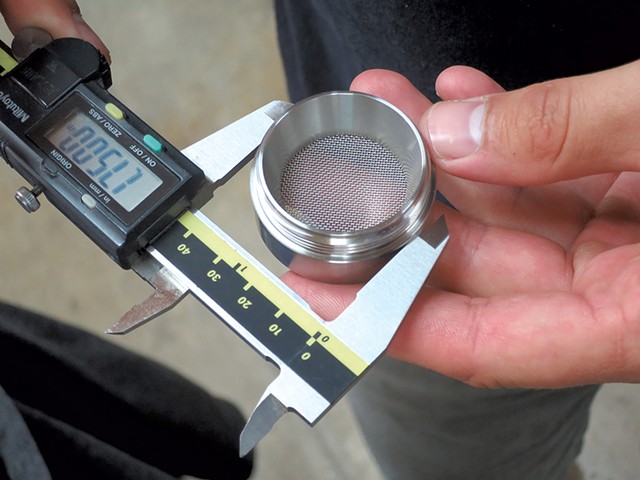

- Cannabis grinder

Headquarters: Essex Junction

Workforce: 6

2016 sales: Not disclosed

It's fitting that Bosnian-born Emir Heco heads up a small manufacturing shop in Essex Junction that prides itself on bringing back-of-the-napkin sketches to reality. "The best ideas come from scratching your own itch," explained the 32-year-old CEO of Heco Engineering, who fled Sarajevo at age 11 to make a new life for himself in the U.S.

Inside a tidy red barn, the young entrepreneur leads a team of six in designing and fabricating a wide range of products from start to finish, including cannabis grinders, lamps and helicopter vibration sensors.

"A one-stop shop," Heco offered. The black T-shirt he wore last Thursday proclaimed simply, "Make Things."

Two employees were working on a wind tower bat deterrent for Hinesburg-based NRG Systems. "It's a bat scarecrow, if you will," Heco said of the license-plate-sized contraption with small, high-frequency speakers that blast out sounds the flying creatures don't like.

When the giant wind-powered blades kill bats or other endangered creatures, companies such as NRG may have to cease operation to figure out why, he explained. "So that's a ton of potential money lost," said Heco, and he should know. Heco started working at NRG when he was a student at the University of Vermont and, after earning his degree, stayed on as an engineer for eight years.

The young problem solver had already learned to be adaptable. Back in Sarajevo, "My father was a toolmaker and a machinist. I spent a lot of time playing around with some of those things," Heco recalled. When the war broke out there, his father joined the army. Shrapnel from a rocket-propelled grenade killed him in 1993, when Heco was 8.

Three years later, the boy came to Vermont with his mother and brother, and the family of war refugees settled in Essex Junction. Emir graduated from Essex High School knowing he wanted to be an engineer and maybe run his own business some day.

He was still working at NRG when his mother was involved in a car accident that left her paralyzed — the seat went backward on impact because of a design flaw attributed to Wisconsin-based Johnson Controls. In 2013, a jury awarded Dzemila Heco, Emir Heco and his brother Kenan Heco $43.1 million in one of the largest personal-injury settlements in Vermont history.

Heco left NRG to work as a consultant for a year, offering design and maker solutions before opening his small shop off Old Stage Road. Since 2015, he and his team have been making parts and finished products and testing prototypes for clients, small and large. The place feels more like a fun and funky tech startup than a manufacturing plant. Cows graze outside in an adjacent field, and inside, the walls are decorated with vintage hand saws.

Heco is attracting local business: He pointed to a high-end porcelain lamp the firm helped produce for Burlington designer Tabbatha Henry.

It's earned some national contracts, too: Heco showed off a small wind-resistant clamp being designed to better secure Go-Pro video cameras to skydiving helmets. The company is also producing a marijuana grinder for a West Coast business Heco would not name. With a sleek design, and "quick-coupling" easy-open top, the grinder prototype is a luxury item in the marijuana consumer products industry.

Two large, computerized machines occupy the center of the shop — a milling machine and a lathe programmed to cut into metal. Off in a corner, Heco keeps earlier versions of the same tools. The old stuff intrigues him because it shows how far manufacturing has come. The 1970s machinery ran on levers that someone had to turn, all day long. "Now we push a button and walk away," Heco explained.

Well, not quite, he allowed. He and his team of engineers and experienced machinists take a drawing and upload it to a computer. Then they program the machines to cut, stamp and finish metal according to specifications. Things don't always go as planned, necessitating adjustments to both the design and manufacturing.

But the orders keep on coming. The company is expanding — to a new, 14,000-square-foot warehouse now under construction at Essex's Saxon Hill Industrial Park. Heco is hoping to move by the end of the year, buy more manufacturing machines and possibly hire more employees.

For talent, Heco looks to Vermont Technical College; he spent a year there after high school before transferring to UVM. This summer he's expecting an intern from the school, and he's got a pilot project going with its manufacturing program. Private companies use Vermont Tech's machines and students to make various products and parts on contract.

The idea is to give companies such as Heco Engineering a better pool of trained employees — as it is, Heco said, small manufacturing firms often have to poach experienced machinists and programmers from other employers to get the talent they need.

Many students ask why they must learn foundation math, machining and engineering concepts and don't see how those fields connect to the real world, Heco added. Bringing actual work their way keeps them engaged. "We have a giant opportunity now."

— M.W.

Mack Molding: Making a Lifestyle

- Molly Walsh

- Jeff Somple, president of Mack Molding, looking out over the plant floor

Headquarters: Arlington

Workforce: 2,200 worldwide, including 550 in Vermont

2016 sales: $350 million

What passes for excitement in Arlington, Vt. doesn't always win over young professionals in the manufacturing business. Mack Molding president Jeff Somple sighed as he recounted how a 27-year-old engineer quit because "there was nothing to do" in the southern Vermont town of 2,300, and he couldn't find a girlfriend.

"He had no social life," Somple said during an interview May 30 in his office on the sylvan campus, where a company "game cam" regularly captures footage of bears in the surrounding woods.

Somple considers it a good sign when a job candidate drives into the company parking lot with a kayak strapped to the car roof or a pair of hiking boots in the back seat. It shows that the applicant might be a good fit at the rural plant that offers free fly-fishing clinics to employees. The trout-filled Battenkill River is nearby.

"You're really looking for people who want to invest in the lifestyle," explained Somple.

Mack is one of Vermont's most successful and versatile manufacturers, with a total of about 550 employees at three plants: two in Arlington and one in Cavendish. Its parent company, Mack Group, has a longer reach. Also headquartered in Arlington, it employs more than 2,000 workers at 11 sites around the U.S. and Mexico.

The company is best known for molding plastic and once made the tiny houses and hotels used in the Monopoly board game. But its product line today is much more diverse. Inside the company's vast, 320,000-square-foot plant — a cavernous space that amounts to roughly seven acres under one roof — workers make parts for 3-D printers, warehouse robots, milk shake machines and medical equipment.

In a room that smelled like Play-Doh, a plastic-injection molding machine as long as a semi sucked pellets of plastic from a big cardboard bin, heated them in a metal barrel and molded them into a placemat-shaped filter for an environmental remediation product. The sole worker on the machine stood at the far end, collecting and stacking the filters as they plopped out, one by one.

In another part of the plant, a laser machine cut openings into a piece of sheet metal; in a sterile "clean room," workers assembled medical equipment. Other workers put together the sheet-metal frame of f'real brand blenders, snapped handles onto surgical trays, measured parts for quality control, and helped move finished products or raw materials around the plant.

At 11:45 a.m., an electronic pinging noise interrupted the sound of humming fans and motors to announce the lunch break. While some shift workers headed to the cafeteria, others made a beeline to the company fitness center to play squash, practice yoga or take a "body pump" class. As part of Mack's wellness program, medical professionals make regular on-site visits to treat minor aches and pains, check blood pressure and encourage healthy behaviors. A Biggest Winner competition motivates employees to lose weight.

Despite the perks, recruiting can be a challenge in a low-population area. To find engineers, Mack offers a paid summer internship to students earning four-year degrees at schools around the country. Rutland-raised Margaret Clark, 19, is earning her mechanical engineering degree from Virginia Tech. She's home for the summer working at Mack. On May 30, she was toiling alongside a senior engineer to program a laser printer that would inscribe the handle of a surgical instrument.

"I like it so far, it's really exciting," she said from behind safety glasses.

The company also recruits interns and workers from the University of Vermont and Vermont Technical College.

But a large number of the plant's employees do assembly work for an hourly wage. Those who come straight out of high school are encouraged to attend courses at Community College of Vermont, which has a campus 20 miles south in Bennington. Luke Darwell, a line leader in the medical tray production area, grew up fixing computers for fun. With encouragement from the company, the 27-year-old is taking courses at CCV and hopes to complete an engineering degree someday. The training is also helping him find "quicker ways to get the product out the door," he said.

Mack is in Vermont for the same reason IBM was: One of the founders liked the place. Kenneth W. Macksey and Donald S. Kendall teamed up in New Jersey back in 1920. Nineteen years later, Kendall moved part of the operation to an icebox factory in Arlington because he liked to hunt and fish and eventually split off from the original company to stay in Vermont. Last year the Mack Group logged revenues of $350 million, up from $335 million in 2015.

Business is good, Somple said, partly because the company has found a sweet spot in manufacturing that he likes to refer to as the "BBC" — big, bulky and complicated. It makes solar-powered streetlights and a photopheresis machine used to treat people with cancer. According to Somple, those kinds of parts or finished products are harder for U.S. companies to make overseas in cheap-labor markets.

"People are very nervous about China now," Somple said, noting that President Donald Trump's mixed signals on tariffs appear to be spurring new interest in U.S. manufacturing.

That anxiety won't likely result in more Mack plants in Vermont. Somple said the combination of the state's relatively high utility costs, taxes and development scrutiny make it a more difficult place to expand than other parts of the country, such as the Southeast.

But the company is bringing in new contracts — several, for example, to make parts for 3-D printers and warehouse robots. Mack hopes to hire another 75 to 100 people in Arlington in the coming year or so, including future engineers from the intern pool, Somple said.

"Our goal is that some of these kids [will] want to come back and want to have a career at Mack."

— M.W.

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.