- Courtesy of The Artist And Hall Art Foundation

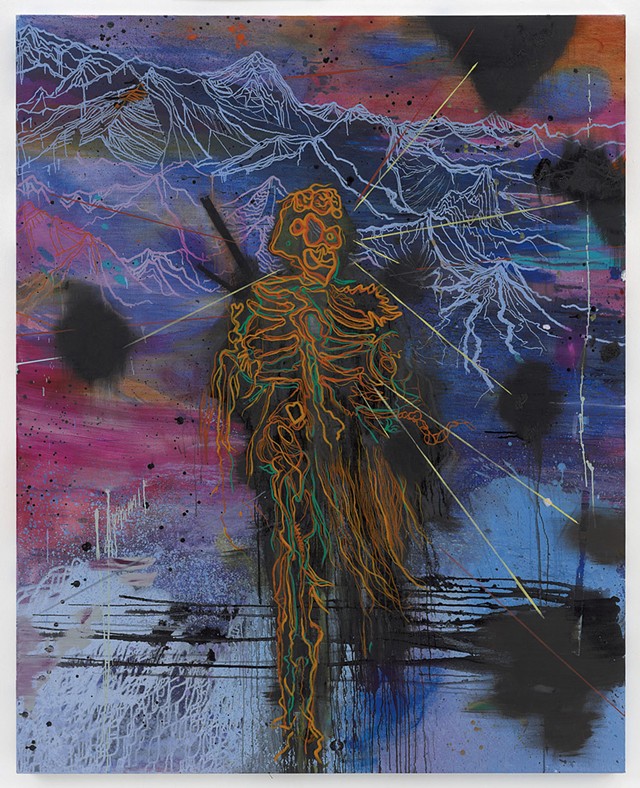

- "Hero No. 1" by Daniel Richter

The color blue has proved visually compelling at least since the Chinese began making blue-on-white-patterned ceramics during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) using cobalt ores from Persia. "Deep Blue," the main exhibition at the Hall Art Foundation this year, is a testament to the color's continued fascination for artists — in particular, painter Katherine Bradford, who guest-curated the show.

Bradford chose the exhibition's 70-plus works from a true treasure trove. The Hall Art Foundation, despite its location in the tiny village of Reading, is home to what is surely the largest, deepest collection of postwar and contemporary art in the state.

British-born collectors Andrew and Christine Hall established the foundation in 2007 to bring their collection of more than 5,000 works of art to the public. The foundation's Vermont site opened as an exhibition space in 2012. It hosts artist-curated shows from May through November in five beautifully rehabilitated dairy-farm structures distributed along a picturesque stream. (The Halls also own a castle in Derneburg, Germany, and lease an industrial shed at MASS MoCA in North Adams, Mass., to show their collection.)

The Reading location has a welcome addition this year: a café, where Brownsville Butcher & Pantry serves up lunch fare using locally sourced ingredients. The new dining area is a coolly toned modern scene: white furniture, garage windows and poured-concrete floor. The single red accent — a lighted neon sign reading "Exhibition" — was created by Glasgow-based artist David Shrigley.

"Deep Blue" is displayed in the farmhouse, cow barn and pole barn. Bradford's interest in blue is also evident in her own work, a selection of which is exhibited in the horse barn and collectively titled "Philosophers' Clambake."

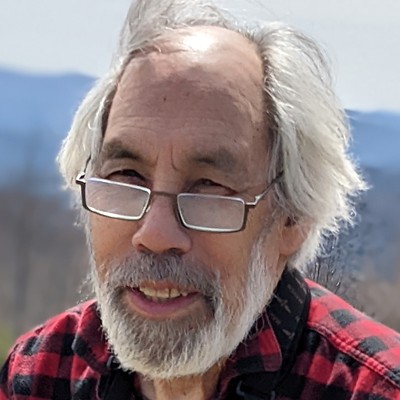

A 79-year-old artist who splits her time between New York City and Maine, Bradford is a self-taught painter who went on to teach at the Yale School of Art, among other institutions, and win a Joan Mitchell Foundation award in 2012. Her color-dense paintings often explore surfers, swimmers and other figures in water.

- Courtesy of The Artist And Hall Art Foundation

- "Holiday After Dark" by Katherine Bradford

"Holiday After Dark" (2018), an Henri Matisse-like composition of roughly rendered figures who seem to be diving into or treading water, depicts them in an ambiguous dark-blue, dot-speckled depth that could also be stellar: a view into deep space.

In trawling both the foundation's and the Halls' personal collections, Bradford found work that reflects her fascination with blue and depth. Due to the pandemic, she performed this task virtually. She also "installed" the exhibition remotely with the help of Maryse Brand, the Halls' daughter-in-law, who created a SketchUp of the galleries for the purpose.

Brand directs the foundation and opened the buildings to this reporter for a self-led tour. New this year is the lack of docents; visitors go from gallery to gallery on their own.

- Courtesy of Jeffrey Nintzel And Hall Art Foundation

- From left: "Untitled" by Anish Kapoor, "Untitled (Blue Wedge)" by John McCracken and "Untitled" by Olivier Mosset

Three sculptural works in a corner of the cow barn form a geometric trio. The largest is John McCracken's freestanding "Untitled (Blue Wedge)" (1968), a 96-by-48-inch right triangle in fiberglass over wood. The artist laboriously applied by hand its faultless Caribbean-blue finish of lacquer and polyester resin.

On the wall hangs Olivier Mosset's "Untitled" (1993-2014), a vertically aligned, rectangular canvas whose color — a depthless midnight blue in polyurethane and acrylic — somehow defies the flatness of its form. From the adjacent wall protrudes Anish Kapoor's "Untitled" (1992), a sliced-off sphere — resembling a giant Amazon Echo Spot — in a deep violet blue. Its viewer-facing flat surface is inscrutable.

"What are we seeing when we look into a blue, vast void?" Bradford asks in an audio-clip commentary on the three works. (Visitors can access all labels and the curator's occasional commentaries via a QR code posted in each gallery.) "Do these objects turn into a feeling of air?" she continues. Though she leaves those questions hanging, blue in the three sculptures is a confrontation with existence and its meaning that eliminates reassuring points of reference.

- Courtesy of The Artist And Hall Art Foundation

- "Vénus Bleue" by Yves Klein

Most of the artists Bradford chose use blue simply because they love or loved the color. Yves Klein famously invented his own deep-purply blue, which he patented as International Klein Blue in 1960. One of his "Vénus Bleue" sculptures, a plaster copy of a Louvre torso saturated in the color, is in the pole barn.

In a beautiful pairing of works on paper in the farmhouse, Joan Mitchell's "Untitled, Diptych" (date unknown) and Richard Diebenkorn's "Untitled" (1981) hang side by side. Both American artists fell in love with the blues of their surroundings — Mitchell with the wild blue cornflowers of France, where she lived much of her life; Diebenkorn with the clear blues of the California sky and ocean. Mitchell's uninhibited, thickly applied scribbles of blue pastel crayon, which densely fill the paper, emanate joyous energy.

"These two are masters of blue," Bradford comments in an audio clip, "and if there was a Matisse next to them, you would have the complete hall of fame of artists who ... loved the color blue."

More complicated in their use of the hue are four monumental paintings facing each other in the center of the cow barn. Their makers are all German, three of them born in the former East Germany. The Halls have extensive collections of German postwar art, and not just the large-scale Anselm Kiefers that fill the shed at MASS MoCA. They're acquiring one of every multiple that Joseph Beuys created and own many of Georg Baselitz's works — not to mention the Derneburg castle where Baselitz lived and painted for 30 years.

Of the four central paintings, "Aquageddon" (2007), by Baselitz student Norbert Bisky, is the most nightmarish. The painting is overwhelming not just in its size (110 by 157 inches) but in the realism of its apocalyptic scene.

The work depicts young men with idealized bodies — a potent symbol in Communist East Germany, where Bisky grew up — variously bored through with a telephone pole, crucified, having desperate sex or pulling each other from a sinking house. The painting's blues morph from night sky to black hole to towering tsunami to almost gel-like floodwaters; blue facilitates the instability and destruction of the scene.

Daniel Richter's "Hero No. 1" (2011) references Baselitz's hero paintings of 1965-66, as well as the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. In it, a skull-headed soldier runs toward the viewer, its figure entirely formed of what look like live wires, orange and pulsing. Oddly, the mountain range behind the figure is suggested with the same wire-like outlines but in a cool blue, as if the environment remains unaffected by war.

The third painting, Jörg Immendorff's "Neue Mehrheit" ("New Majority") (1983), features a menacing group of eagles — symbolizing West Germany — joined by a swastika. Immendorff studied with Beuys; the two shared an interest in the sociopolitical power of art.

A.R. Penck, Immendorff's friend and fellow East German, painted the fourth work, the Keith Haring-like "Kooperation" (2002). The painting's two black stick figures with arms raised could just as easily be about to attack each other as to cooperate; the neutral light-blue background offers no clue.

The risk of remote curation is evident in the pole barn, where Bradford's audio clip describes the "gorgeously blue" shade of Chris Martin's "Samuel Palmer" (2007). The virtual image of the painting is indeed a dark blue, but in reality the painting is gray. Beside it, the flat periwinkle of Andy Warhol's "Flowers" (1978) correctly matches its digital image.

Far from focusing on big names, Andrew Hall continues to search for little-known artists he deems undervalued — finding them mostly on Instagram these days, according to Brand. Then he collects them in depth, a canny investment strategy that must also be loads of fun.

Hall's finds include East Burke painter Terry Ekasala. One of her works first appeared in the Hall's 2018 "Made in Vermont" exhibition; now she has a solo show in the visitors' center.

Much has been written about the Halls' source of funding: Andrew is an oil-commodities trader whose promised $100 million bonus in 2009, from a Citigroup company bailed out by taxpayers, sparked public outrage. Nevertheless, it's laudable that the couple decided to share their art collection with the public — not a given at their level. And their decision to locate the foundation near their Reading home, rather than their Palm Beach or New York abodes, is an asset to Vermont.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.