- Courtesy of Generator

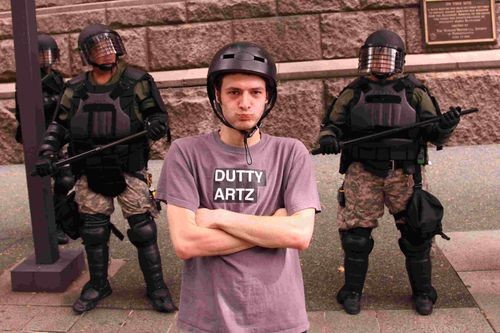

- Paolo Pedercini

The event room on the third floor of the Center for Communication and Creative Media at Champlain College was packed to the brim last night. The third Big Maker event by Burlington's Generator introduced game designer Paolo Pedercini.

After welcoming remarks from CCM Dean Dr. Paula Willoquet-Maricondi, Generator's executive director Lars Hasselblad Torres stepped up to the podium to introduce the series and Pedercini, an assistant professor of experimental game design at Carnegie Mellon University.

"Big Maker is a series of discussions about big and interesting ideas," Torres said. He added that the series aims to drive entrepreneurial endeavors in the state by providing opportunities for makers to connect with people such as Pedercini.

"We're excited to have Paolo because he brings a deep perspective on games and activism," Torres said. "It's exciting to have talent out there that's pushing the boundaries on what games are capable of."

For someone like this reporter, who has barely touched a video game since she played The Oregon Trail with her brother in the early 2000s, it might be hard to imagine how games could create such a buzz. Those unfamiliar with the field might know only about violent games such as Call of Duty, the quasi-historical fiction of Assassin's Creed, or the strange visual realism of FIFA games.

But as soon as Pedercini took the stage, with his animated facial expressions and still-prominent Italian accent (he's originally from northern Italy), a different picture of the field emerged — one more in line with the provocative aspects of street art. In fact, his statement of interest in "practices that intervene in the public, physical and media space" could have come straight from the mouth of any street artist.

Pedercini made that interest in disruption clear by playing an excerpt from "Faith Fighter," one of the many games he has produced and published on his website Molleindustria. The game, which now provides a disclaimer to warn audiences that they might be offended by the content, pits religious figures such as God, Buddha, Ganesha and Muhammad against each other in animated combat.

Later in the evening, when discussing censorship and whether artists and designers should worry about offending their audience, Pedercini acknowledged that, in a gallery setting, it would be easy for someone to see "Faith Fighter" as offensive. But, he continued, "I don't think it's offensive. It's cartoonish, it's kind of shitting on every religion." He noted that a British tabloid tried to make the case that it was an intolerant game. Pedercini sees it instead as "discussing intolerance."

"The first challenge to making games, for me," he said, "is making games that deal with real issues, to go beyond the escapist function of video games that have to be about saving princesses, collecting money, taking you to a magical world." Making games that provide players with the illusion of reality doesn't appeal to him. Rather, Pedercini prefers to use illusion and abstraction to connect people to reality.

The designer rolled through demonstrations of a few of his many games. Every Day the Same Dream is described on the Molleindustria website as "a game about alienation and refusal of labor." Visually, it's a beautiful piece, primarily black and white with soft, scratchy music playing in the background. It depicts a faceless, two-dimensional man completing mundane actions such as dressing, getting stuck in traffic on his way to work, and being yelled at by his boss. When his day ends, the cycle begins again.

"You're stuck in this endless routine," Pedercini said from the stage, watching the little man prance toward his cubicle on the projector screen, "but there are things in there that break the traditional gaming convention. You can walk left instead of right. Or you can get out of your car in traffic and go pet a cow."

Same Dream is, as the title suggests, dreamy. But some of Pedercini's games are more astringent in their criticism of society. McDonald's Videogame criticizes fast-food systems and their impact on the environment and political systems. Oiligarchy focuses on the relationship between politics and the oil industry. Phone Story takes users through the environmental and social impacts of smartphone manufacturing.

After Pedercini's lecture, CCM curator Chris Thompson moderated a short conversation with the designer and a Q&A session with the audience. Conversations circulated around the role of fun in games, the ups and downs of being an indie game designer, and more technical aspects of game production.

The Q&A session was relatively short, with time for only three audience members to take the mic. Georgette Garbes Putzel, founder of Theatre Mosaic Mond, closed out the night with an observation rather than a question:

"I'm pleased to hear what you bring here," she said to Pedercini. "But I don't know if the people who are learning how to create games are going to be in an academic environment where, in addition to learning how to create this technically, they'll have semantics classes, theology, philosophy, where they'll end up creating something that's not only entertaining, but that makes you think."

Her comment touched on the limitations of traditional academic systems, which often confine students to coursework related to their major. That concern is exactly why spaces like Generator and events like Big Maker exist: to promote cross-pollination and transdisciplinary activity.

As the crowd drifted out of the room, Thompson said to this reporter, "Generator is all about: How do you get artists to engage with technology?" He sees Pedercini as a perfect example of the intersect of art and technology. "He's appropriating elements from the video-game milieu and turning them into art," Thompson said.

Paolo Pedercini's exhibit "Radical Games" — featuring video games that address gun control, religious hypocrisy and corporate greed — is on view through February 6 at the Center for Communication and Creative Media gallery, Champlain College, in Burlington.

The next Big Maker event on March 3 will feature David Moinina Sengeh, from MIT Media Lab, whose research focuses on prosthetics.

Speaking of...

-

Video Guide: Things to Do in Vermont During the Eclipse

Jan 25, 2024 -

Flipping Out at the IFPA Vermont State Pinball Championship

Jan 25, 2023 -

Video: Married Artists Jennifer Koch & Gregg Blasdel Collaborate Together & Collect Art

Dec 1, 2022 -

Video: Tom Locatell Hews Fallen Trees at Gilbrook Nature Area in Winooski

May 20, 2021 -

Teen Harrison Brooks Invents New Card Game, ElevatorUp

Jul 29, 2020 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.