- Alcon Entertainment / Silver Pictures

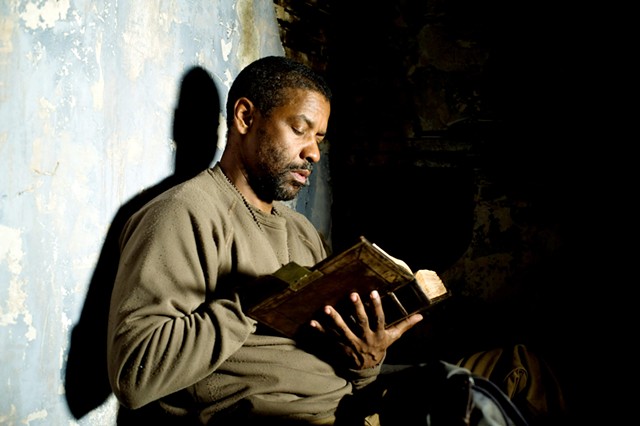

- Denzel Washington as a postapocalyptic badass in The Book of Eli

When I saw The Book of Eli on its release in 2010, I was impressed with its visuals, in particular with a virtuoso gunfight scene that appears to play out in a single long take. I’m always drawn to long-take films, in large part because they offer such a valuable alternative to an increasingly edit-happy modern cinema.

In reality, the gunfight scene was not pulled off in a single take: As the camera zips between the combatants inside an isolated farmhouse and those mounting the assault outside, the transitions between these two spaces are digitally smoothed over. The result is that a multi-shot scene has the urgency and breathless pacing of a single-shot scene. To me, the capacity to create such a scene is one of the most important changes to film style that the digital age has produced.

Viewing The Book of Eli for the second time last week, I was again impressed by that scene, as well as by the movie’s overall visual scheme. The postapocalyptic world in which the story takes place is pleasingly monochromatic to my eye. This time, though, I found myself focusing on the various and clever ways in which the film’s directors, the Hughes Brothers, keep the story’s “secret” from viewers.

The movie reveals little about Eli’s past. Was he a soldier? A spy? How did he get his incredible battlefield skills? One of the few clues we do get — a glimpse of his old nametag from Kmart, where he apparently worked “in the world before” — merely complicates matters. Department-store clerks are not often skilled in the martial arts.

Here begin the aforementioned spoilers.

- Alcon Entertainment / Silver Pictures

- The Book of Eli

But the decision not to reveal Eli’s blindness presents the filmmakers with a dilemma: How do they keep this fact from viewers, especially when Denzel Washington, who plays Eli, appears in the great majority of the film’s shots? The solutions that the Hughes Brothers found for this problem reveal them, once again (as if From Hell wasn’t proof enough), to possess a visual intelligence of a very high order.

On my second viewing, I watched with an eye to checking if the directors ever tipped their hand, either accidentally or deliberately. I couldn’t find any examples of their doing so.

One simple strategy that helps a great deal: have Eli wear sunglasses most of the time. Not all the time, because that would get suspicious; anyway, everyone in this film wears sunglasses while outdoors because of some ill-specified fallout from the war. But he does typically wear them during the scenes in which, for instance, he quickly slices up half a dozen highwaymen.

Oddly, though, the swordfight scenes are the scenes that pose the least threat to revealing the twist. That’s partly because of the long and venerable history of films about blind swordsmen. The 26-film (and 100-television-episode) Zatoichi series is the most important of these; it was remade in the West as the underrated Blind Fury in 1990, and again in 2003, as Zatoichi, by none other than Takeshi Kitano.

- Alcon Entertainment / Silver Pictures

- Eli reading his book

Eli also carries an iPod he’s found somewhere, on which he (wisely) listens to Al Green. It’s an older iPod model, the kind that makes those little clickety sounds as one operates its buttons. At one point the battery loses its juice, and Eli is eager to recharge it. In a clever shot, taken from behind, he holds the device up to test whether it might still contain a little charge. The shot is taken from such an angle, and the camera mounted with such a lens, that it’s impossible to tell whether Eli is holding up the iPod visually to check its display, or aurally to check whether it’s still making the clicking noises that indicate operation. In retrospect, we realize that it’s the latter, but the framing and lens choice keep the film’s secret from us.

- Alcon Entertainment / Silver Pictures

- Looking at the iPod, or listening for the iPod's click? The framing makes it difficult to tell.

At other times, it’s Washington’s subtle performance that keeps us from knowing the twist ahead of time. In an early scene, Eli enters an abandoned house to search for any items that he might use or barter. One shot is positioned so that it looks through an open kitchen shelf as Eli runs his hand along its interior. Without looking directly at them, he brushes aside plates and bowls, finding nothing of value. It’s only in retrospect that we can read this shot as depicting the actions of a blind man; as Washington performs it, his eyes are fixed on a wall to the right, so the fact that he doesn’t look at the contents of the shelf as he touches them suggests merely that he performs the action idly.

We can read the shot this way only because Washington gives the movement a certain casualness. A moment later, Eli opens a closet and finds a young man who has hanged himself; he takes the man’s boots, exactly the objects he’d hoped to find. Eli holds a cloth to his nose to stifle the stench of rotting flesh, but we learn only later that he actually used his sense of smell to find the closet. He appeared to be staring at it as his hands brushed along the shelves, when in fact he was following his nose.

- Alcon Entertainment / Silver Pictures

- It's impossible to know whether Eli isn't looking at the shelf or simply can't see it.

If you’ve seen this film, I encourage you to watch it again, being especially cognizant of the strategies the directors use to keep the twist from the audience. If you haven’t yet seen it but went ahead and read this column anyway, well, you can’t say I didn’t warn you. But perhaps I’ve suggested a way to watch it that enriches this accomplished film.

Speaking of...

-

A New Film Explores Vermont’s Unsung Modernist Buildings

Mar 20, 2024 -

A Film Critic Pays Final Respects to the Palace 9

Nov 11, 2023 -

Director Jay Craven Wins 10th Annual Herb Lockwood Prize

Oct 21, 2023 -

Book Review: 'Save Me a Seat! A Life With Movies,' Rick Winston

Aug 30, 2023 -

Steve MacQueen Named Executive Director of Vermont International Film Festival

May 22, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.