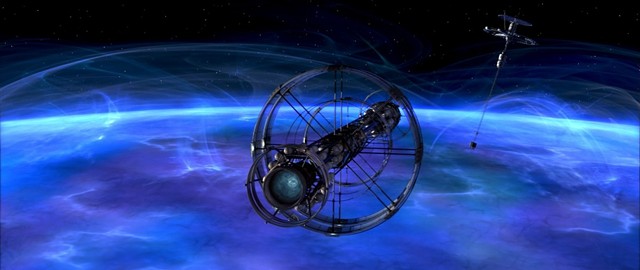

- Twentieth Century Fox / Lightstorm Entertainment

- George Clooney and Natasha McElhone in Solaris (2002)

I’m not particularly drawn to the story of Solaris, I’ll admit, and I can think of other novel-to-film-to-film transformations that are more interesting to me. Off the top of my head, the 1956 and the 1978 versions of Invasion of the Body Snatchers come to mind; so do the 1920 and 1941 versions of Jack London’s novel The Sea Wolf. I’m not that into those authors, either, but I am always curious to see how stories can be interpreted and presented in multiple ways. Lem’s novel, and the films made from it, fit the bill for this project. And there were all the texts, right there in my living room, so what the hell.

Lem himself lived long enough (he died at age 84 in 2006) to release a statement about Soderbergh’s version of his novel. Though the author was obviously an intelligent and thoughtful man, we probably should not make too much of that statement, as Lem admits in its second paragraph that he has not even seen the movie.

Even so, Lem refers (disparagingly) to the single biggest difference between the source novel and Soderbergh’s film. The novel (as well as Tarkovsky’s film) is far more invested in the science fiction elements of the story, using the protagonist’s relationship with his wife (or “wife”) as a way to explore such notions as the nature of identity and reality. Soderbergh’s film is essentially about the relationship between the protagonist, Kris Kelvin, and the spontaneously generated version of his late wife, Rheya, who is somehow created by ill-understood forces on the planet Solaris, above which hovers the space station that Kelvin visits.

In dissing Soderbergh’s film, Lem snarkily remarks that his book was titled Solaris and not Love in Outer Space. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with making a film about a love story that takes place in outer space, just as I feel that love is no less valid a subject for a text than are brainy meditations on the nature of reality. As I remarked in my story about the 1972 Solaris, I actually find such meditations somewhat dull and navel-gazey; to me, an interstellar love story sounds more appealingly unusual than does Lem’s more traditional (and I use that term cautiously) science fiction approach.

Why not set a love story in space? It probably hasn’t been done all that often, so it might offer new creative possibilities to a filmmaker. And, as I say, I’m interested in the way that a single story can mean different things to different artists. The love story in Soderbergh’s film is most assuredly present in Lem’s novel; it’s really just a question of the relative emphases that Lem, Tarkovsky and Soderbergh place on the various and complex elements of Solaris.

- Twentieth Century Fox / Lightstorm Entertainment

- Natasha McElhone as Rheya in Solaris

We first see Kris and Rheya interact via a dream/flashback that Kris experiences during his first night on the space station. Here their first meeting is presented in the context of an ambiguity that is never resolved. The two characters chance to sit across from each other on a train, and Kris notices that Rheya is clutching a doorknob. No purse, no jacket — just a doorknob.

It’s an odd moment (not present in the novel) that we see Kris ask Rheya about in a later flashback. She playfully avoids answering him, and the matter never comes up again. Viewers never know the significance, if any, of the doorknob, and, so far as we know, neither does Kris. Their relationship is born in an ambiguity that only intensifies as the film progresses — a straightforward parallel to the deepening sci-fi ambiguity that structures the novel and the 1972 film. Soderbergh may not have made a literal adaptation of the novel, but it seems to me that his adaptation is very much in its spirit.

- Twentieth Century Fox / Lightstorm Entertainment

- The ambiguous doorknob in Solaris (2002)

The ambiguity of Kris’ and Rheya’s relationship intensifies in several important ways. First, and most important, Rheya commits suicide back on Earth. She does so after Kris becomes enraged because she got an abortion before telling him that she was pregnant (a narrative device not in the novel). She is dead, yet somehow reappears, with elements of her personality and even some of her memories intact, on the space station.

How is this possible? None of the versions of Solaris ever answer this question. Even though Rheya may not be real (or “herself”), Kris begins to fall in love with her. But his reasons for doing so are ambiguous, too. Is it because he feels guilty about being an indirect cause of her death? Is it because he has genuinely fallen in love with this new version of Rheya, despite her mysterious, interstellar origins?

If it’s the latter, then the ambiguities increase: If we can fall in love with facsimiles of human beings, what is the nature of love? Indeed, if the capacity to love is not an essential human quality, then what is the nature of humanity? Such questions, I would argue, are not only in the spirit of Lem’s inquiries into human nature, but are in fact identical to the questions he asks. The author needn’t have dismissed Soderbergh’s film so quickly (and without actual knowledge of it). Turns out they were interested in the same ideas.

The most interesting thing about Soderbergh’s Solaris is not the multifaceted nature of its ambiguous love story, but the very fact that such ambiguity exists in a mass-market film like this one. The two most essential qualities of Hollywood storytelling are clarity and coherence, that is: Does each story element make sense in and of itself, and do those story elements, when juxtaposed, create a story that makes sense according to temporal, spatial and causal principles? One might even refer to the twin pillars of clarity and coherence as the “mission” of Hollywood cinema, which aims to generate profit by presenting stories that will be understood and enjoyed by as many people as possible. That’s a fairly crude way to put it, but it’s not inaccurate.

- Twentieth Century Fox / Lightstorm Entertainment

- The space station hovers around the mysterious, possibly cognizant planet Solaris.

Yet Solaris does both — and well, I think. How did such an unusual film pass muster with studio bean counters? It’s hard to know, but it probably had something to do with Soderbergh’s proven box-office track record (in 2002, he’d recently come off two huge successes: Erin Brockovich [2000] and Ocean’s Eleven [2001]), and with the presence of James Cameron, who pretty much has carte blanche with every studio in Hollywood, as one of Solaris’ producers.

Because it is an ambiguous film released by a major Hollywood studio, Steven Soderbergh’s version of Solaris is arguably more unusual than is Andrei Tarkovsky’s more self-consciously “artful” exploration of the same source novel. I wouldn’t say that I love any of the three versions of Solaris that I’ve recently engaged with, but I’m inspired and even heartened by the fact that the story has proven itself so compelling for these three very different artists.

- Twentieth Century Fox / Lightstorm Entertainment

- Clooney's expression aptly sums up the ambiguity in Solaris.

Speaking of...

-

Book Review: 'The Princess of Las Vegas,' Chris Bohjalian

Mar 20, 2024 -

A New Film Explores Vermont’s Unsung Modernist Buildings

Mar 20, 2024 -

Book Review: 'The General and Julia' by Jon Clinch

Feb 21, 2024 -

A Film Critic Pays Final Respects to the Palace 9

Nov 11, 2023 -

Director Jay Craven Wins 10th Annual Herb Lockwood Prize

Oct 21, 2023 - More »

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.