- Paula Routly

- Long view of Salvation Mountain

Near the dusty town of Nilan, Vermont-born Leonard Knight spent three decades building a monument to God called Salvation Mountain. A vision of obsessive devotion topped with a cross, it marks the entrance to a squatters’ paradise called Slab City, aka The Slabs, that was featured in the 2007 movie Into the Wild. Knight and his mountain were also in the film.

- Paula Routly

- Salvation Mountain from above

In 2000, the Folk Art Society of America declared it a “folk art site worthy of preservation and protection.” In an address to the U.S. Congress two years later, California Sen. Barbara Boxer called Salvation Mountain a “national treasure … profoundly strange and beautifully accessible, and worthy of the international acclaim it receives.”

- Paula Routly

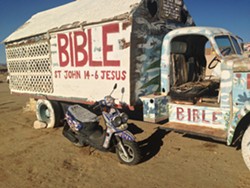

- Converted vehicle at Salvation Mountain

- Paula Routly

- Room inside Salvation Mountain

In the same speech, Boxer described Knight as “a one-time snow shoveler from Vermont.” The official Salvation Mountain website, which doesn’t appear to acknowledge his death, notes he was born on November 1, 1931, just outside of Burlington in “Shelburne Falls” — the fourth of six kids.

A staff-written obituary last February in the L.A. Times said Knight was “a welder, handyman, guitar teacher, painter and body-and-fender man” before he arrived in Slab City in the early 1980s with his truck, an old tractor and a hot-air balloon that he had once thought would be his conveyance for a cross-country float.” He spent decades living alone — among stray cats — in a truck at the base of his mountain. Plenty more of those converted vehicles remain.

All Knight ever asked for was paint.

- Paula Routly

- Salvation Mountain

“He never sought to proselytize. He greeted visitors cheerfully,” Tony Perry wrote in the Times obituary. He quoted Knight from an earlier encounter: “If somebody gave me $100,000 a week to move somewhere and live in a mansion and be a big shot, I’d refuse it,” he said. “I want to be right here. It’s amazing, isn’t it?”

Last week, in the blazing California sun, I couldn’t have agreed more.

- Paula Routly

- A "sign" on Salvation Mountain

Speaking of...

-

Video: Married Artists Jennifer Koch & Gregg Blasdel Collaborate Together & Collect Art

Dec 1, 2022 -

The Cannabis Catch-Up: Troubling Signs for Legal Markets?

Aug 16, 2019 -

The Cannabis Catch-Up: Will the Feds Legalize Hemp Cultivation?

Mar 30, 2018 -

Three Vermont Exhibits Showcase Self-Taught Art

Jul 20, 2016 -

Vermonter at NYC's Outsider Art Fair

Jan 21, 2016 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.