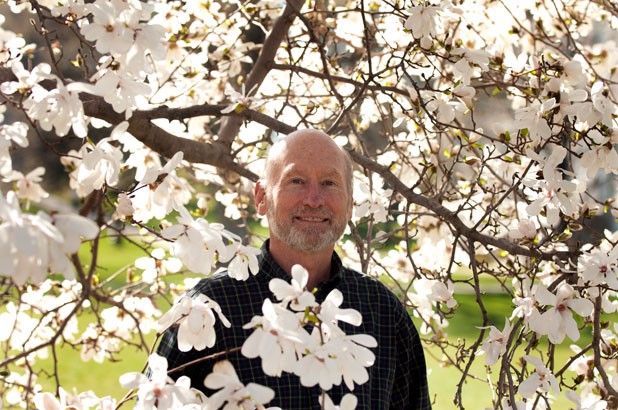

- John Elder

Slender, gray-bearded 63-year-old John Elder doesn’t look like the eco-orgy type. But chat with him a while in his spartan Middlebury College office, and the soon-to-be-retired professor will tell you: What the green movement needs is “a big party like Mardi Gras.” And let’s not ignore “the erotics of conservation,” Elder urges.

But Elder follows his solicitation to party hearty with a warning that “the largest need we have as Middle Americans is to restrain our appetites.” In Elder’s estimation, “we’re piggy — we all are.”

He’s hoping the fat and the stupid will slim down and wise up before their hyperconsumption renders the planet unlivable. “It’s conceivable — by no means guaranteed — that we’ll make the necessary changes to avoid catastrophic climate change,” Elder reckons.

Such visionary — and tenuously optimistic — observations have inspired generations of Middlebury College students who have learned from Elder, a 21st-century nature writer as perceptive and poetic as John McPhee, Bill Bryson and Bill McKibben. Appropriately, Middlebury is celebrating Elder’s career with a flurry of events on and around Earth Day.

“They knock me out,” Elder says of the attitudes and initiatives of today’s students. “They give me a lot of hope. This current generation of college students and their children,” he proclaims, “will be the central generations in human history.”

Elder started teaching environmentalist courses after several years in Middlebury’s Department of English and American Literatures. The Bay Area native, who says he’s always enjoyed the outdoors, developed a late-blooming love for nature writing not so much from reading the likes of Thoreau as from tromping in fields and woodlands near his beloved homestead in Bristol. His most celebrated work, Reading the Mountains of Home , chronicles a series of hikes in those environs, weaving in reflections on other writers’ work — most notably, Robert Frost and his poem “Directive.”

Elder appreciates “the Thoreauvian sense of solitude in wilderness” because it allows for transcendence of what William Wordsworth, one of his favorite poets, scorned as the triviality of “getting and spending.” Living in the spirit of Thoreau, Elder adds, “it’s easy to fall into a kind of intellectually Luddite position” that spurns all things digital. But even though he’s not on Facebook and doesn’t tweet, Elder sees social networks as powerfully positive.

“Obama wouldn’t have been elected without cellphones and the Internet, and the supreme leader of Iran would sleep better at night without them,” he observes. At the same time, “there are losses as well as gains” from the new technologies, Elder adds, citing the erosion of book culture as one of the big losses.

Despite having spent his entire adult life in academia — as an undergraduate at Pomona College, a graduate student at Yale and a prof at Middlebury since 1973 — Elder views himself as an activist. He identifies closely with the environmental movement, describing it as “this country’s great contribution to world culture: that and jazz.” He’s leery, however, of the movement’s traditional focus on “prohibitions and purity.” Elder finds that “urban Americans and people of color have put forward a compelling critique” of that nature-centered ethic. In response, “the movement has been realigning in the last 10 to 15 years, putting greater emphasis on social justice and nontranscendentalist ways of loving nature.” Elder supports those efforts, which he describes as “more of an invitational approach that relishes the diversity of our communities.”

It’s one thing to invite others to savor the natural world. But when it comes to climate change, Elder believes we have no choice but to wake up and start taking practical action. His characteristic combination of bookishness and outdoorsmanship has led him to the conviction that “climate change is a fact that cannot be evaded.” That’s the consensus among climatologists, he points out. And he knows from direct experience that Vermont’s seasons aren’t the same now as a few decades ago. “You can really see that as a sugar maker,” Elder says.

He and his wife, Rita, a retired special educator, tap a Starksboro sugarbush every spring with help from their two adult sons, Caleb and Matthew, who live on adjoining lots on the 142-acre property. (A daughter, Rachel, works in Brooklyn as a TV producer.) Matthew’s twin 3-year-old sons are recent recruits to the Elder sugaring crew. A photo of the boys sampling sap from a tap is one of the few adornments of Grandpa’s booked-up office.

In addition to the flavor — said to be exceptionally good this year — and the money he makes from selling his syrup, Elder values sugaring as “a culturally and historically rich experience.” He wrote a book about it, too, called The Frog Run. Sugaring is one of the charms of Vermont that has rooted him in the state as firmly as a fine old maple. “I’ll never leave here,” Elder promises.

Vermont’s wooded wilderness may not be as “sublime” as California’s panoramas, but he’d have to drive several hours from San Francisco to glimpse them, Elder points out. Here, “I walk out my door in Bristol and see bear tracks.” Vermont’s balance of natural and cultural quality may be unmatched, he suggests. Mere hours after inspecting those bear tracks, Elder notes, he can take in a performance of Irish music at the Flynn.

The Irish inflection is important. Although he’s of Scottish descent — which, as Elder observes, isn’t at all the same as being Irish — he and his wife join in a seisiún every evening at home, with Rita playing concertina and John accompanying her on whistle and flute. He taught himself both instruments three years ago, when he was 60.

“John’s not stale,” reports Middlebury dance professor Andrea Olsen, who describes him as “a complex human being. He’s always trying to stay ahead of the norm.” Olsen co-taught a “Nature and Creativity” class with Elder that stressed “experiential learning.”

Kate Lupo, a senior who took the course last semester, says it was “unlike any I’ve had at Middlebury.” Classes began with yoga warm-ups and would include dancing and discussions of environmental essays in the college’s organic garden. “Instead of feeling nervous, as I often do in classes, I felt relieved in this one,” Lupo says.

She regards Elder as “a great role model in terms of public speaking and in his ability to connect on a personal level.” He’s a “forceful communicator,” Lupo adds — “very persuasive and eloquent. He argues passionately for what he cares about.”

Elder appears to enjoy an unblemished reputation among Middlebury students, past and present. Jennifer Sahn, who graduated in 1992, remembers him as “dynamic and thrilling” in the classroom. “He’s passionate about what he teaches, which is the hallmark of a good teacher,” adds Sahn, who found postgrad work at Orion, an environmentalist magazine based in Massachusetts. Elder helped her gain entrée to the publication that she now edits.

Professional groups and peers at other institutions have also recognized Elder’s excellence in pedagogy. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching named him Vermont Professor of the Year in 2008.

Given all those accolades, isn’t it hard to put down your chalk and pack up your satchel? Elder was asked. He admits to feeling a “pang” of sorrow at leaving Middlebury, but he seems more excited than upset at the prospect of no longer teaching. “I’m looking forward to what happens in a less institutionally framed life,” Elder says. “Teaching has trumped everything for me. I want to see what happens when it doesn’t trump everything.”

It’s not as though he’s going to be riding a golf cart around Florida. Elder has been working for the past four years on a “half-memoir” that combines his musings on a variety of subjects with a natural history of the Hogback Range, which includes Mount Abe and runs past Bristol, Starksboro and Monkton. He also intends to teach an occasional summer course at Middlebury’s Bread Loaf School of English.

Since the college has no mandatory retirement age, “I’m choosing to refocus a little earlier than I might have,” Elder says. “I’m making a little space for myself here and now, because, of course, we are not immortal.”

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.