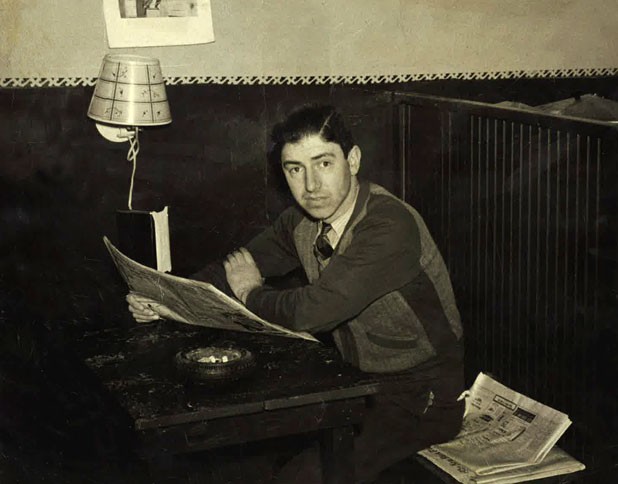

- Alec Klinkostein in his deli

A kosher deli on North Union Street? A butcher who would kill chickens while you waited? Backyard ritual slaughter of cows? While the current residents of Burlington’s Old North End may pride themselves on their urban agriculture, they can’t compare to the hardworking immigrants of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Back then, the Old North End was home to “Little Jerusalem,” a settlement of Jews who had emigrated from the area of Kovno, Lithuania. They rebuilt their Eastern European community in the Queen City, complete with kosher butchers; bakeries that cooked both bread and Sabbath meals; and, of course, backyard chickens and even cows to be slaughtered by the friendly neighborhood shochet.

Seven Days rebuilt a picture of all this through first-person interviews, Burlington city directories and books such as Myron Samuelson’s 1976 The Story of the Jewish Community of Burlington, Vermont.

The settlement was first documented around 1880, when a group of 20 Jews began congregating for prayers. Burlington’s first synagogue was built in 1887 and was quickly followed by another two years later. At that time, 40 families inhabited Little Jerusalem. Most of them were peddlers. By 1900, many of those peddlers had settled down to open one of Burlington’s 11 Jewish-owned grocery stores. Just like today, “pop-ups” (or, at that time, carts) often begat brick-and-mortar businesses.

Inspired by Little Jerusalem, a recent documentary from Vermont Public Television, Seven Days spoke to a passel of former residents of the long-gone Jewish community about its food and flavors. We tracked them down in their current haunts, from Naples, Fla., to Auburn, Maine.

Annette Lazarus, now 86, was the daughter of cantor Morris Nadelson. As a holy man, Nadelson had a meaty role in the community — literally. He was a shochet, schooled in the ritual slaughter that made backyard animals into kosher dinners.

Lazarus remembers begging her father to let her join him as he said the prayers and carefully cut the throat of an animal. “They chained [the animals, including cattle and lambs]. To this day, I can hear the rattling of the chains,” says the Middlebury resident. “I like animals, and I guess I never should have gone.”

Lazarus’ father, whom she remembers as an exceptionally gentle man, was apparently none too keen on the ritual, either. She recalls that after he retired, he turned vegetarian. “We were big meat eaters,” Lazarus says. “But after retiring, he stopped. He wouldn’t say why, but I knew why.”

In the later days of Little Jerusalem, when Jews were better integrated into the community and increasingly secularized, Nadelson worried that no one would follow in his footsteps. A youth named George Saiger thought he might fit the shochet bill, and, at age 17, he gave a dissertation at the synagogue to announce his intentions.

“Mr. Nadelson started giving me lessons on Sabbath afternoons,” remembers Saiger, now 73. “I failed miserably. I could not decipher a single line of Talmud.” Still, Saiger has pleasant memories of the more gruesome aspects of his studies. “I remember Mr. Nadelson telling me, during one of our sessions, that the insides of a cow’s stomach was unbelievably hot,” he says. “If the cow had swallowed a nail long enough before you slaughtered it, the nail would be largely melted due to that heat!”

In the end, Nadelson didn’t find a successor. A Montréal shochet performed Little Jerusalem’s final ritual slaughter in 1960, for Burlington-based Solomon’s Wholesale Beef, later Solomon Casket.

While kosher beef was in high demand in Little Jerusalem, local, grass-fed beef didn’t have the cachet in the early 20th century that it does today. Ed Colodny, 86, whose grandfather, father and uncle each owned a popular nonkosher grocery store, says his family preferred to get its kosher beef from Abraham Fleishman at 37 Bright Street.

“His beef was western beef,” says Colodny, an esteemed lawyer and one-time University of Vermont interim president currently wintering in Florida. “It was a little bit more expensive [than beef supplied to butchers by the shochet]. Not a lot, but some.” However, given the cuts that religious law permitted the kosher butcher to provide, even that beef was far from tender. “No sirloin or T-bone steaks,” Colodny says with a chuckle.

Saiger remembers that he and the other kids referred to Fleishman as “Snoodgeh” behind his back. But by the midcentury era, the younger man can remember, Snoodgeh was just a meat wholesaler. The town’s two remaining kosher butchers — known as Little Fishman and Big Fishman — were each other’s only real competition.

Dorothy Sussman Fishman remembers those sobriquets well. Now a resident of Auburn, Maine, she lived in Little Jerusalem in the late 1940s with her in-laws, Sarah and Morris Fishman, while her husband, Louis, attended medical school. Fishman recounts that her father-in-law originally came to Vermont from Detroit to help his brother, Joseph, in his meat business. When the two brothers’ wives didn’t get along, Morris Fishman got lessons in cutting meat, then opened his own store.

Known as Little Fishman — though his daughter-in-law remembers both men as diminutive — Morris was the more popular butcher with Seven Days’ Little Jerusalem interviewees. None preferred visiting Joseph’s 259 North Winooski Avenue location over having a cup of tea at Morris’ at 114 Archibald Street, before picking up chickens slaughtered right at the house.

“My father-in-law was a very, very unassuming, very, very quiet man,” Dorothy Fishman recalls. “The other one [Joseph Fishman] was always talking and complaining. The meat [at Morris’] wasn’t any better.”

Eighty-year-old David Hershberg begs to differ. “I know my mother was very fond of Little Fishman,” he says. “She thought he ran a very good and clean shop. If she went there, it had to be good — she was very fussy.”

Most interviewees say they left the meat purchasing to their mothers. They were of the younger generation that enjoyed dining outside the home. And the only place to do that and keep kosher was at Morris Klinkostein’s Kosher Delicatessen and Fancy Groceries, better known as “Klink’s.”

The North Union Street delicatessen is not mentioned in Burlington city directories, so it’s difficult to pinpoint the years it was active. According to Morris Klinkostein’s grandson, Brian Kling, his grandfather opened the deli, which started as just a grocery store. Kling’s father, Alec, and uncle, Frank, sold the business in the early 1940s when they enlisted to fight in World War II. The deli closed a few years later, and the brothers returned to run the space next door as a photography business.

“They were wonderful brothers,” Colodny recalls of the Klinkosteins. “It was a hangout for Jewish kids in the North End. They had kosher deli foods, but not like New York. Not like the 2nd Ave Deli. They had the salami and the bologna, the corned beef, smoked salmon, all that. The basics were there.”

Kling wasn’t born until the late 1950s, when the deli was long gone. But a neon sign his family passed down tells him that Klink’s sold Hebrew National meats. Often too much. Kling says his father told stories of having to reduce the size of Frank’s enormous sandwiches before serving them, along with a pickle straight from a barrel.

Lazarus and Hershberg agree that their peers weren’t really at the deli for the food, anyway. “There never has been another kosher restaurant in Burlington,” Lazarus says. “It was unusual because it was all young people gathered there.”

Hershberg adds, “We thought it was pretty good, but when you go to places like the Stage Deli [in Manhattan] — [Klink’s] didn’t really have very much. Klink’s was a gathering place. It was a social thing as much as it was anything else.”

Where there’s a deli, there’s often fresh-baked bread. Klink’s served its sandwiches on pumpernickel bread from baker Samuel Goldberg, Hershberg recalls. Goldberg began baking at 681 Riverside Avenue in the 1920s, back when it was known as First Street. Right across the street at 666 Riverside Avenue, Abraham Cohen competed with him at a business eventually called Cohen’s Stone Oven Bakery.

Hershberg’s family patronized Goldberg — but not always for his bread. His oven was the perfect place to cook a brisket on the Sabbath, when religious law prohibited the family from switching on their own oven. “You could take the worst piece of meat, and if you put it in a crock pot with beans and potatoes, you could give the Goldbergs a dollar to put it in their oven,” Hershberg says. In the winter, he recalls, he’d bring the pot to the store on his sled. “They would add water to it, and after synagogue on Saturday, we would eat it. You could have a pretty tough piece of meat, and after cooking for 24 hours, it tasted like filet mignon.”

On Sundays, Goldberg’s sold bagels — a business that would stay in the family long after they stopped baking pumpernickel loaves. Today, a descendant, Ron Goldberg, and his family own the Bagel Market in Essex Junction.

That café-market is one of the few traceable offshoots of the once-thriving food businesses of Little Jerusalem. The demand for Jewish foods died away with the neighborhood, and most former residents say they have long since stopped keeping kosher.

Where do they go when they want a nostalgic taste of old-time Burlington? To the strip-malls of South Burlington. Saiger, who now lives in Washington, D.C., says that when he visits the Queen City, he special orders meat from the Shelburne Road Price Chopper. The market’s Jewish deli, Ben & Bill’s, isn’t strictly kosher, but several former Little Jerusalemites say it’s their favorite destination for a taste of time gone by.

Meanwhile, the Old North End has once again become ground zero for the cuisines of recent immigrants. Vietnamese banh mi and Persian pitas have replaced deli sandwiches, while African markets specialize in halal meats slaughtered with rituals not unlike those Nadelson practiced. The countries of origin have changed, but for New Americans, the neighborhood is still the best place to get a taste of home.

This article was titled "Tastes of Little Jerusalem" in print.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.