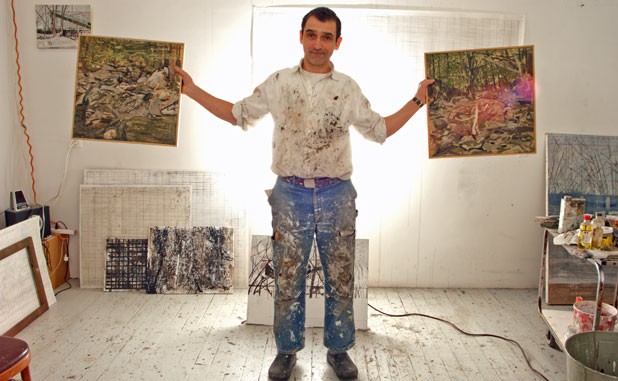

- Matthew Thorsen

- Peter Fried

The scene visible from Peter Fried’s studio on Pine Street in Burlington couldn’t be less stereotypically Vermont. Instead of a stand of sugar maples, he sees a tangle of telephone wires. And that’s no dairy barn across the way — it’s the Maltex Building.

“I want to paint what I see with a loving eye,” Fried comments in a lilting Scottish accent. And what he sees near his home as well as his studio is the postindustrial detritus of South End rail yards: rusting trains, graffiti-tagged trucks, weedy and pollution-tolerant ailanthus trees. Fried also depicts shopping-plaza parking lots and rain-swept stretches of I-89, complete with looming exit signs.

What’s the attraction to images more associated with New Jersey? “Human-made forms are proliferating,” Fried says simply. “They’re what’s around us, including here. Are they really ugly? Have you ever looked at them with an inquisitive eye and an open mind?”

Fried’s gimlet-eyed approach to his subject matter arises from a hard-won philosophy of life based on Buddhism. While a patient for a year in a London mental hospital, “I made a pact with myself that I’d study Buddhism when I got out,” Fried explains matter-of-factly. “I had to find a way to heal myself, and Buddhism basically saved my life.”

Hunched in paint-splattered overalls, Fried, 51, speaks with precision and no trace of self-pity about the rocky journey that took him from Prague to Edinburgh to London, and then on to Colorado, Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom and now here: a white-walled studio in a former brush factory behind Speeder & Earl’s Coffee Roastery.

Fried’s relationship with his father mainly accounted for the emotional torments he experienced in his twenties, he reveals. The elder Fried was a Czech Jew whose carpentry skills enabled him to avoid the ovens during three-and-a-half years of captivity in the Nazis’ Terezin concentration camp. He survived until 1986, but in withered, gnarled form, the son recounts. His father had come to identify with the Nazis and behave like them, just as hostages sometimes express empathy with their abductors in a psychological phenomenon known as Stockholm syndrome.

Fried the father was not only unsupportive of his son’s artistic interests, he belittled them and ridiculed the boy for exhibiting “effeminate” inclinations. But Fried’s mother had trained as a social-realist painter in Prague and strongly encouraged her son to develop his talent.

At age 6, Fried moved with his family from Communist Czechoslovakia to his mother’s native Scotland. It wasn’t the sort of liberating lifting of the Iron Curtain that the democratic-capitalist side in the Cold War would assume it must be. “The atmosphere for children growing up in Czechoslovakia under Communism was better than in Scotland,” Fried recalls. “In the Slav countries, people are very loving. It wasn’t that way with the Scots.”

Fried enrolled in the prestigious Saint Martins College of Art and Design (now called University of the Arts London/Central Saint Martins) when he was 18, and then in the Slade School of Fine Art for graduate work. He had access in both places to some of the big names in British art. Among them was Lucian Freud, known for his unsparingly realistic nudes, as well as surviving members and disciples of the Euston Road School, a group of naturalist-realist painters formed in the 1930s.

Fried laments not taking better advantage of the teachings of these traditionalists. “I was too whacked out,” he says. “I hung out with crazy dudes who did whatever they wanted to do.”

Looking back, Fried sees his art-school self as “a disaster waiting to happen.” He was so troubled that he checked into the Henderson Hospital, a London therapeutic institution noted for its co-op-like organizational structure.

He then turned to Buddhism as a spiritual discipline, Fried relates. “When I meditated, I would see my mind as it was at that moment and allow myself not to take it so seriously. Emotions do come into it,” Fried continues, “but it’s like I’m reading my emotions instead of being blown away by them.”

Buddhism also brought Fried to America. He lived at the Karmê Chöling Shambhala Meditation Center in Barnet, Vt., from 1995 to ’99. Then, at a Buddhist center in Colorado, he met his future wife, native Vermonter Annelies Smith. It was there, too, that a teacher persuaded Fried to devote himself to painting.

Embracing an artistic vocation relatively late in life heightens the challenge, already formidable in Vermont, of earning a living as a painter. “There’s not a particularly strong buying public here,” Fried points out, noting he’ll soon need to get at least a part-time job. But he has made some sales at arts events. Exposure at the Taste of Stowe Arts Festival helped Fried gain entry to the Helen Day Art Center, where a show of his paintings remains on display through February 27.

Visitors will see that, in addition to his urban realism, Fried favors an abstract minimalism, exploring the theme of grids that Agnes Martin infused with a sense of the sublime and the transcendent. Fried is quick to acknowledge that his grids represent “an homage” to the late Canadian American painter, who was herself a student of Zen Buddhism. Martin’s paintings, he says, fill him with “a serenity and a calm that I really need.”

Traces of grids can be seen in many of Fried’s paintings of highways and derelict tractor-trailers. Sometimes they hover as thin lines in the background, poking out from a landscape Fried has laid over them in a muted palette; in other works, the grid takes the form of trees and fences in the foreground.

It can take three months to complete one of his midsize paintings, Fried says — partly because he’s working on other pieces at the same time. He prefers to compose en plein air, though that’s been impossible much of this winter. Second best is working from photographs, though, he notes, they “can’t give you the changes in light, the sounds, the passing by of people that you get when you’re outdoors.”

Fried also favors oil paint, which he calls “more mischievous” to work with than acrylic. He adds, “Oil’s got an attitude.”

And so does Fried — profane and gentle, sad eyed and funny, and as bouncy in his enthusiasm as a Buddhist can be.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.