Stumps are not what come to mind when you think about the Hudson River School. The 19th-century landscape painters were, after all, known for their portrayal of unsullied natural splendor, for their endorsement of the philosophy that Nature is sublime and Man, by comparison, is insignificant. But lopped-off trees are common to many of the paintings of Charles Louis Heyde, currently exhibited, after many years out of limelight, at the University of Vermont’s Fleming Museum.

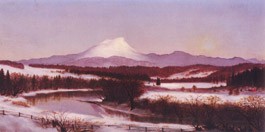

Heyde (pronounced hi-dee) is considered a latter-day Hudson River School painter, with the notable difference that he lived and painted for most of his career in Burlington, not upstate New York. Fifty-seven of his works have been collected by guest curators Tom Pierce and Eleazar Durfee for “Old Summits, Far-Surrounding Vales: The Vermont Landscape Paintings of Charles Louis Heyde,” and they are glorious.

Glorious? With stumps? Yes. In fact, it takes careful observation to even notice that some of the denuded hillsides show the remains of old-growth forests, which were cleared in great quantities for sheep and crop farming in mid-19th century Vermont. It takes even longer, in some cases, to notice a tiny human figure or two — often a fisherman or hunter. That’s a testament to the powerful, ample beauty of the land, nestled beneath Green Mountains, as well as to Heyde’s focus and reverent attention to light.

Though some of these paintings have darkened over time, there’s no obscuring their breath-taking luminosity. Like other painters of his era, Heyde seems to have been especially enamored of those precious, fleeting moments between day and evening — the evanescent netherlight that blankets the countryside, softening and enriching its hues. Sunsets over Lake Champlain were a favorite subject, and the fields and gently rolling hills backed by Mount Mansfield also inspired many a canvas.

We can’t know what Heyde thought when he surveyed these scenes. Did he include the tree stumps, the creeping evidence of human industry and environmental alteration, as an ecological statement? It’s tempting to think that, knowing what we know now, but it’s just as likely Heyde’s paintings are simply honest, accurate depictions of what he saw, and without judgment. After all, he couldn’t have imagined what other forces would soon encroach on his beloved terrain. If he noted the activity of loggers, the coming of the railroad, the settling in of villages, Vermont was still far more Edenic than the sprawl-threatened state it would become.

Heyde’s subject matter — scenes familiar to us even without the present-day roads, buildings, telephone wires and snarls of traffic — makes the paintings poignantly interesting to a Vermont audience, and all the more precious because many of these pristine views are gone forever. Indeed, at the show’s opening last Sunday, viewers marveled with delight when they recognized various locales painstakingly researched by the curators: an aspect of Mountain Mansfield from the east side of the rise at UVM; a particular bend in Otter Creek; a sunset at Shelburne Point; an Adirondack view from a hill in St. Albans; the High Bridge in Winooski. It’s easy to feel somewhat proprietary about such an art show: Heyde was one of our own. This early flatlander, as Fleming Director Ann Porter puts it, “portrayed why we all live in Vermont.”

It was the faithful representation of natural beauty that drew buyers to Heyde’s studio on Pearl Street during his most productive years in Burlington — the sign hanging outside it read “C.L. Heyde, Painter of Vermont Scenery.” Many paintings remained in families through generations, and Pierce found them hanging over mantels or stored unceremoniously in attics. Some ended up in the Fleming and Shelburne museums, the Fletcher Free Library, and with numerous other collectors in Vermont. Deep local ties to Heyde’s work lend the current exhibit special significance, a feeling somewhat akin to a family reunion with relatives you didn’t know you had.

But because the style has been out of fashion in the art marketplace, and perhaps because Heyde was less famous than some of his contemporaries, his complete oeuvre had never been catalogued — the last Fleming retrospective of 30 Heyde paintings was in 1965. So locating the works for this show required some serious sleuthing. It didn’t help that the artist failed to sign many of them — Pierce says some owners didn’t know they had a Heyde until he and Durfee identified it.

That’s why the two were surprised and thrilled to turn up not only 80 of 84 known works — these previously identified by Shelburne curator Barbara Knapp Hamblett for her 1977 master’s thesis — but another 74 as well. That brings to 154 the number of artworks now “locatable,” Pierce says with relish.

But why the search for Heyde in the first place? And why now? “I seem to recall that it just evolved out of discussions,” says Porter. “We’d been talking about the importance of putting a focus on Vermont art, art important to the community, and not just contemporary art, which is what we’d been doing.”

Pierce, a member of the Fleming’s advisory board, is more explicit: “In conjunction with the millennium, we thought we should have a Vermont landscape exhibit,” he says, noting the significance of looking back a century as we enter a new one. “I love contemporary art, but I also love to see those classic 19th-century paintings; I can’t see them enough.”

The board and staff agreed. Because he and the Fleming both owned Heydes, Pierce says, he was interested in the artist. “I’ve seen them around, families I know have them, but they’re never on public display,” he explains. “I thought if we could get some of these paintings [shown], what a magnificent collection it would be. Over more time, paintings get more dispersed.”

Pierce began to direct his considerable energy into a search for Charles Louis Heyde. But he wasn’t alone: third-generation Vermonter Lee Durfee, trained as an archivist and knowledgeable about art, joined in, helping to identify paintings and photographing what they found. It became obvious the duo was right for the job, says Porter, “once we saw the kind of detail, the energy and commitment… Pretty quickly we realized we were working with two guest curators who would be really dedicated.”

Pierce, 53, is a partner at Michael Kehoe, a men’s clothier in downtown Burlington. Raised in Connecticut, he came to Vermont to attend St. Michael’s College, and, after four post-graduate years in New York City, returned to the Green Mountain State for its quality of life. He grew up in a family that appreciated art, as did Durfee, whose parents are collectors. Durfee, 36, works in marketing for a local academic publisher and had done some archiving for the Fleming before. But neither of the men had ever participated in anything quite like this.

“I just like projects and I felt strongly about this one,” downplays Pierce. “I think Lee did also… the project just escalated to much larger than we had envisioned.”

And just how do you find missing paintings? “Word of mouth, mostly,” Pierce says. For example, “I went to someone’s house, and the housekeeper said, ‘I know someone else who has one.’ We also placed ads in magazines, researched auction records and talked to galleries — they would forward letters to people who had bought a Heyde over the years.”

Most of the search was in the Northeast, but Pierce did track down a painting as far away as Alaska — owned by the daughter of a Burlington family who had moved there.

For Durfee the greatest thrill was discovering a completely unknown painting. “As the project continued, we came to know the art work better, and became more professional,” he says. Durfee and Pierce gradually acquired expert eyes for spotting Heydes, even learning the types and brands of frames the painter commonly used. In choosing works for the show, their only clear criterion was quality. “If it wasn’t good, we’d continue,” Durfee says. He notes that owners were generally interested and helpful, and “99 percent were totally willing and enthusiastic” about loaning their paintings. Only one or two said no. “But we had enough to choose from, so it wasn’t a big concern — we didn’t really need another Mansfield,” Durfee quips.

He and Pierce had intended to hang their exhibit in 2000, but the research ended up taking two years. It was worth the wait.

Unlike the minute brush strokes in his paintings, the details of Charles Louis Heyde’s early life are sketchy. Historians seem fairly confident that he was born in France in 1822, the son of a Philadelphia ship captain who had been lost at sea. Barbara Knapp Hamblett, whose biographical research informs the catalogue assembled for the current Fleming exhibit, says nothing of the young Heyde’s mother. His childhood was spent, apparently uneventfully, in Pennsylvania.

Heyde was in his early thirties when he first set foot in Vermont. He came in 1852 with his new bride, Hannah, a sister of the poet Walt Whitman. Earlier evidence of Heyde’s development as an artist came from exhibition records at the National Design Academy and New Jersey Art Union. He lived for a while in Hoboken and in Brooklyn.

Thanks to the volume of letters saved by the Whitman family, we know that the Heydes were somewhat itinerant for the next four years and spent much time in southern Vermont, around North Dorset, Bellows Falls and Rutland. Some of his most Elysian paintings, several featuring Saxtons River, come from this period. By 1856, the Queen City beckoned, and Heyde and his wife settled in Burlington, where they stayed for the remaining 36 years of his life.

Heyde, painting beautifully in the favored style of the day, soon caught the attention of the Daily Free Press editor, George Grenville Benedict, who became a patron. But the success didn’t last. A friend noted in 1863 that Heyde “painted to live” — a financial reality still familiar to most artists — and had to churn out numerous small works to earn his bread and butter. Some of his paintings were traded for goods and services.

Additionally, Hannah and “Charlie” Heyde, who remained childless, had a tumultuous relationship, according to those revelatory Whitman family letters. Walt himself reportedly sent money to his sister on occasion. Heyde, a poet in modest measure himself, had a falling out with his famous brother-in-law over the years.

In fact, the painter seems to have grown increasingly bitter, irascible and slovenly — as well as alcoholic — especially as interest in his art work waned with the advent of photography. Was it something in the paints that caused his growing dementia? Hamblett doesn’t presume to know, but the records are clear that Heyde was eventually committed to the Vermont State Asylum in Waterbury, where he died ignominiously in 1892. Heyde was survived by his wife and two sisters.

The survival of his paintings is a much happier affair, and an exhibit honoring the productive years of a great Vermont artist seems an appropriate marking for the turn of this century. Indeed, community interest in “Old Summits, Far-Surrounding Vales” — a title taken from one of Heyde’s poems — is keen: The Key Bank is a major sponsor, as is the State of Vermont; the handsome catalogue was designed by Burlington graphic artist Tina Christensen and edited by Nancy Price Graff and Tom Pierce. Middlebury conservator Randy Smith helped clean and restore some of the paintings; Burlington photographer Ken Burris shot the paintings for the catalogue. At the opening last Sunday, Vermont Life editor Tom Slayton delivered a lecture placing Heyde in art-historical context. His own essay will appear in the spring issue of the state-sanctioned magazine, adding to the considerable publicity the show has already generated. What’s more, Heyde now has a Web site — www.charleslouisheyde.com — courtesy of the Fleming Museum.

More than 100 years after his death, Heyde has arrived, 21st-century style.

Programming in conjunction with “Old Summits, Far-Surrounding Vales” includes two lunchtime lectures at the Fleming Museum: “Charles Louis Heyde and the Legacy of the Hudson River School Painters,” by UVM art professor William Lipke, on January 31; and “Rediscovering Charles Louis Heyde’s Vermont Landscapes,” by Tom Pierce and Eleazar Durfee, February 14. On March 31, the Fleming will host the daylong “Vermont Landscape Conference: Views of the Past, Visions of the Future.” For more information on these events, call 656-0750.

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.