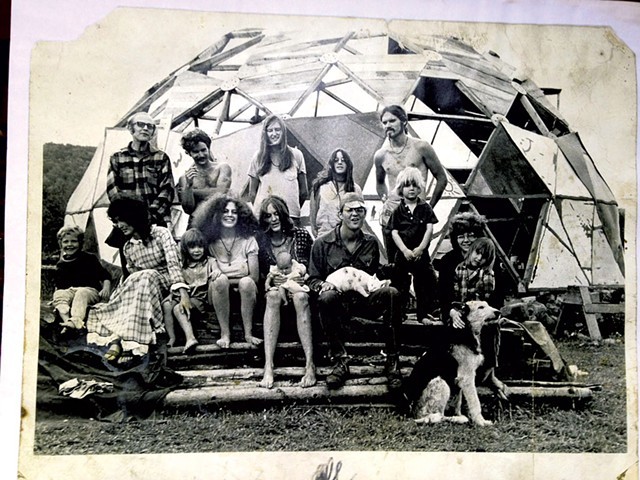

- Courtesy of Goddard College Archives

- Goddard College students, 1971

The daylong event at the Vermont College of Fine Arts in Montpelier, which featured keynote speaker Edward Berkowitz, a cultural history scholar, bore some resemblance to an educational program at a senior center. But the topics weren't the least bit bland. Most of the 125 attendees seated at round tables in the college's Alumni Hall were old enough to recall the riotous 1968 Democratic Party convention in Chicago, the 1969 Woodstock musical festival, the 1970 killings of antiwar demonstrators at Kent State University in Ohio and other tumultuous events of the era recounted by some of the speakers.

- Kevin J. Kelley

- Audience at VHS symposium

“We had no phone, no electricity, no running water,” remembered Mary Mathias, a retired social worker who lived in the '70s on the Frog Run Farm commune in East Charleston. “We thought having a flush toilet was anti-environmental. Why use precious clean water to get rid of wastes?”

Frog Run communards also eschewed chainsaws and other gas-powered equipment, instead using cross-cut saws to fell trees for firewood, and driving draft horses to plow and harvest crops. “We were rejecting civilization as it was,” Mathias explained. “We were going to start everything again.”

- Courtesy of Loraine Janowsky/Public Affairs

- Mullein Hill commune, West Glover 1971

VHS curator Jackie Calder offered a similar assessment while presenting a slide show that included photos of hairy young women and men at snowbound homesteads or in sunny pastures. “They were trying to create the world they wanted to have,” she said.

The colorful and often unkempt newcomers evoked suspicion and fears, as well as hospitality and helpfulness, from their deeply rooted rural neighbors, speakers noted.

“Many Vermonters feared the influence these people would have on their children,” Calder said. “And they were right.” Some of the back-to-the-landers “were integrating into communities and becoming very successful community activists. They did influence government. What people feared would happen, actually did happen.”

Back-to-the-landers were instrumental, symposium speakers agreed, in gradually transforming Vermont into what is arguably the most progressive state in the country. Their values often found fertile ground in a state with a strong tradition of tolerance and good-neighborliness.

Members of the Total Loss Farm commune in Guilford received warm welcomes from long-settled southern Vermonters, said Peter Gould, whose 1971 novel, Burnt Toast, is based on his life there. “We moved to that farm at just the right time,” he remarked. “The local farmers' children were all leaving the land.” The old-timers were pleased to be able to pass on skills to neophyte farmers who were also enthusiastic learners, Gould said.

More thespian and activist than farmer, though, Gould has performed internationally as one half of the politically minded duo Gould & Stearns. A longtime writer and teacher, he works with young students in Brattleboro, and is the founder of the children's theater camp Get Thee to a Funnery in the Northeast Kingdom.

One audience member asked the panel that included historian Scott why the United States of 2016 is facing many of the same problems that the avowed revolutionaries of the 1970s had set out to solve. Was the revolution a failure?

Scott, who teaches at Eastern Mennonite University in Virginia, acknowledged that the full hippie and New Left agenda had not been implemented. But she pointed to successes that were achieved by many movements of the era, including those focused on feminism and gay rights. “Maybe there really was a revolution,” Scott suggested.

- Kevin J. Kelley

- Bill Lippert and Michele Clark on a panel

He had moved to Vermont in 1972 as an antiwar and social-justice activist, recently graduated from Earlham College in Indiana. That was a full three years after the uprising outside the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village that marked the start of the militant gay-rights movement. But Lippert, who identified as gay, said he was nonplussed to find no trace of a gay male community in Vermont.

Earlier in the proceedings, Calder had noted the presence in Vermont of at least two communes composed of radical lesbians, who, she said, had spearheaded the gay-rights movement in the state. “But we're not finding any gay men's communes,” she added. “That wasn't seen as safe at the time.”

Indeed, overt hostility was common, Lippert remembered. Far from hosting gay student groups, the University of Vermont in the early 1970s was “still doing aversive treatment on gay men,” he said.

Only one bar in Burlington, the High Hat Lounge in the Main Street space subsequently occupied by Nectar's, was known as a place gay men were allowed to frequent, Lippert recalled. But the High Hat had “unwritten rules” that included a ban on same-sex dancing, he noted.

“One night we said, 'This is ridiculous,' and started dancing together. The bartender cut us off from drinks. And soon the Burlington police came. We were thrown out and told we would be arrested for trespassing if we went back in,” Lippert said.

- James Collins & Susanna Bowman/VHS archive

- French Hill Commune, St. Albans

Lippert, who has represented Hinesburg in the Statehouse since 1994, may not have entirely accomplished that former objective, but he has clearly succeeded in his latter quest.

As testimonials at the symposium made clear, the spirit of the '70s lives on in the deeds as well as in the memories of some of the Vermonters who devoted their lives to ending war and all forms of injustice.

“It's been 38 years since I left that farm,” Gould said in reference to the Guilford commune where he lived from 1969 to 1978. “Not a single day goes by that I don't think of some aspect of that experience. It was just so rich.”

The symposium was based in part on the results of a two-year survey undertaken by VSH. An exhibition, "Freaks, Radicals & Hippies: Counterculture in 1970s Vermont" opens Saturday, September 24, at the Vermont History Center in Barre. Visit the VHS website for more information about that and additional programming on the topic.

Speaking of...

-

Court Rejects Roxbury's Request to Block School Budget Vote

Apr 24, 2024 -

Q&A: Downtown Montpelier Transforms Into PoemCity Every April

Apr 24, 2024 -

Video: Visiting the Kellogg-Hubbard Library’s PoemCity in Montpelier During the Month of April

Apr 18, 2024 -

Q&A: Catching Up With the Champlain Valley Quilt Guild

Apr 10, 2024 -

Video: 'Stuck in Vermont' During the Eclipse

Apr 9, 2024 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.