- United Artists Pictures

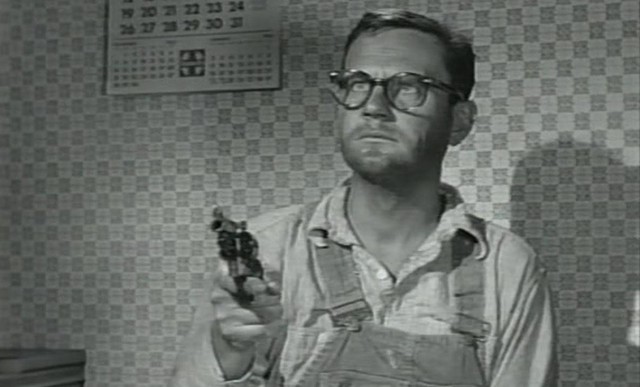

- Wendell Corey in The Killer Is Loose

I am baffled when I hear people complain about the lack of films available on Netflix's streaming service. It's a digitized treasure trove of cinema history, people. It may be that the interface of the Netflix app — which, on the PS3 at least, is highly crappy — does not really encourage digging very deeply. But this is another matter altogether (and one that, honestly, I wish Netflix would address); Netflix's digital library is a vast and wondrous thing. All the more so because, as I understand it, the streaming rights for their films and shows are negotiated on a title-by-title basis. You can be fairly confident that much of your monthly subscription fee funds the health care plans of the company's legion of copyright attorneys.

If, like me, you're fond of old, obscure Hollywood films, you could do a lot worse than trolling through Netflix's catalog. I could watch run-of-the-mill Tim Holt westerns and Virginia Mayo potboilers all day long. A few days ago, as part of my effort to clear out my overloaded queue, I finally got around to watching The Killer Is Loose, 1956 policier directed by one of the all-time greats, Budd Boetticher.

Boetticher's name isn't well known among casual film fans, despite having had a nice DVD box set dedicated to his westerns, the films for which he's best known. He's particularly beloved among cinephiles for his so-called "Ranown" cycle of westerns, seven semi-related films that all star the great Randolph Scott. And these are very great films, notable for their starkly beautiful compositions and overall leanness. Many of them clock in at less than 80 minutes. Indeed, Boetticher's films are notable for their lack of excess of any kind. His heroes speak only when they need to, he'll never use two shots when one will suffice, and very little action does not bear directly on the central story.

Even though my tastes in art (of all kinds) run toward the "more is more" aesthetic, I admire Boetticher greatly, in part because his stylistic approach is so different from that of many of the directors I admire. It would not be inaccurate to compare his films to those of Robert Bresson, another director noted for including only the bare minimum of visual and story information required to make a film comprehensible.

Two shots in The Killer Is Loose really stood out to me as evidence of Boetticher's mastery of visual storytelling. The first occurs in the film's first scene, in which the director uses shot composition, staging of actors and spoken dialogue to very cleverly misdirect our attention.

The two frames below are taken from the first shot to show us the interior of a small bank that is about to be robbed. (We know that something nefarious is afoot because, right before we go inside the bank, we see several shots of stone-faced, shifty-looking fedora'd men "casing the joint.") At left, a teller converses with a woman who apologizes profusely for missing a payment; he assures her in a friendly manner that it's not a big deal. The conversation between these two characters dominates the shot's soundtrack, a fact that draws our attention to the conversants.

- United Artists Pictures

- Misdirection, Step 1: The Killer Is Loose

- United Artists Pictures

- Misdirection, Step 2: The Killer Is Loose

As it happens, though, their conversation, though attention-grabbing, is unimportant. The far more salient exchange is the one that occurs between the two men at frame right, even though it is predicated on a single, unintelligible word that the patron, as he walks to screen left, utters to the teller. That word, whatever it is, is enough to summon the teller also to walk behind the counter, toward frame left with a slightly puzzled look on his face.

Because the conversation between these two other characters is terse and unintelligible, and because the conversation about the missed payment continues, it's easy to miss the exchange between the man in the hat and the teller on the right. But, moments later, we learn that that man in the hat is one of the bank robbers, and that he's summoned the teller in order to command him to empty the bank's vaults. Boetticher is playing a game with us, challenging us to focus our attention on the most narratively salient occurrences — and he doesn't make it easy.

In fact, the conversation between the woman and the teller on the left is important, but only in a way that intensifies the misdirection that Boetticher uses here. It's not until quite a bit later in the film that we learn that that teller, Mr. Poole (Wendell Corey) was the "inside man" for the robbery; indeed, he soon turns out to be the film's titular killer. By showing him, in this shot, as an avuncular fellow — and, soon after, by showing him "attempt to thwart the robbers" in an attempt to make him look innocent of the crime — his later bloodthirstiness is all the more pronounced and ironic.

This very clever shot demonstrates Boetticher's remarkable skill for using compositional and soundtrack elements to confound his audience's grasp of the story. This is not easily accomplished.

A later shot is skillful in a somewhat similar way. A group of policemen, gathered together in a huddle at the stationhouse, confer about the best ways to extend their manhunt to catch Poole, who has hitherto eluded their grasp. Note how, in the image below left, no single man is seen in full-frontal view: The two men at left and the seated man at right are shown in profile, and the main character, Det. Sam Wagner (Joseph Cotten), is seen only from behind. But over Cotten's left shoulder is just visible the forehead of another man, whom we neither see nor hear speak.

- United Artists Pictures

- ... which is exactly what happens, moments later.

- United Artists Pictures

- The "empty" space to the left of the seated man suggests that something important will soon fill it ...

Seconds later, in this same shot, that man steps to frame right, thereby occupying the "empty" space between Cotten and the seated man. When he does so, he sets forth the plan that will ultimately be used to catch Poole.

In order to enhance the validity of this character's scheme, Boetticher not only has him "activate" the previously empty space but positions him so that his face is fully visible. His visual prominence is exactly proportional to the narrative importance of his idea. No need to cut in to a closer shot of him or any such measures; a mere step to the character's left is all Boetticher needs to place visual stress on this key story moment.

Again, this stuff might look easy, but this kind of subtle skill separates the great directors from the merely good.

Speaking of...

-

A New Film Explores Vermont’s Unsung Modernist Buildings

Mar 20, 2024 -

A Film Critic Pays Final Respects to the Palace 9

Nov 11, 2023 -

Next Month Brings the Final Curtain for Palace 9 Cinemas

Oct 27, 2023 -

Director Jay Craven Wins 10th Annual Herb Lockwood Prize

Oct 21, 2023 -

Book Review: 'Save Me a Seat! A Life With Movies,' Rick Winston

Aug 30, 2023 - More »

Comments

Comments are closed.

From 2014-2020, Seven Days allowed readers to comment on all stories posted on our website. While we've appreciated the suggestions and insights, right now Seven Days is prioritizing our core mission — producing high-quality, responsible local journalism — over moderating online debates between readers.

To criticize, correct or praise our reporting, please send us a letter to the editor or send us a tip. We’ll check it out and report the results.

Online comments may return when we have better tech tools for managing them. Thanks for reading.